| Kurukh | |

|---|---|

| Kurux, Oraon, Uraon | |

| कुँड़ुख़ (उराँव), কুড়ুখ্, କୁଡ଼ୁଖ୍ | |

'Kuṛux' or 'Kuṁṛux' in Kurukh Banna alphabet (top) and Tolong Siki alphabet (bottom) | |

| Native to | India, Bangladesh, and Nepal |

| Region | Odisha, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Bihar, Tripura[1] |

| Ethnicity | |

Native speakers | 2.28 million (2002–2011)[2][1][3] |

Dravidian

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Devanagari Odia Kurukh Banna Tolong Siki | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | India

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:kru – Kuruxkxl – Nepali Kurux (Dhangar)xis – Kisan |

| Glottolog | kuru1301 |

| ELP | Nepali Kurux |

| |

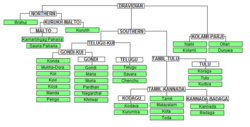

Kurukh (/ˈkʊrʊx/ or /ˈkʊrʊk/;[4] Devanagari: कुँड़ुख़, IPA: [kũɽux]), also Kurux, Oraon or Uranw (Devanagari: उराँव, IPA: [uraːũ̯]),[5] is a North Dravidian language spoken by the Kurukh (Oraon) and Kisan people of East India. It is spoken by about two million people in the Indian states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal, Assam and Tripura, as well as by 65,000 in northern Bangladesh, 28,600 of a dialect called Uranw in Nepal and about 5,000 in Bhutan. The most closely related language to Kurukh is Malto; together with Brahui, all three languages form the North Dravidian branch of the Dravidian language family. It is marked as being in a "vulnerable" state in UNESCO's list of endangered languages.[6] The Kisan dialect has 206,100 speakers as of 2011.

Etymology

According to Edward Tuite Dalton, "Oraon" is an exonym assigned by neighbouring Munda people, meaning "to roam". They call themselves Kurukh.[7] According to Sten Konow, Uraon will mean man as in the Dravidian Kurukh language, the word Urapai, Urapo and Urang means Man. The word Kurukh may be derived from the word Kur or Kurcana means "shout" and "stammer". So Kurukh will mean 'a speaker'.[8]

Classification

Kurukh belongs to the Northern Dravidian group of the Dravidian family languages,[9] and is closely related to Sauria Paharia and Kumarbhag Paharia, which are often together referred to as Malto.[10]

Writing systems

Kurukh is written in Devanagari, a script also used to write Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, Nepali and other Indo-Aryan languages.

In 1991, Basudev Ram Khalkho from Odisha released the Kurukh Banna script. In Sundargarh district of Odisha the Kurukh Banna alphabet is taught and promoted by Kurukh Parha. Fonts have been developed and people are using it widely in books, magazines and other material. The alphabet is also used by Oraon people in the states of Chhattisgarh, Bengal, Jharkhand and Assam.[11]

In 1999, Narayan Oraon, a doctor, invented the alphabetic Tolong Siki script specifically for Kurukh. Many books and magazines have been published in Tolong Siki script, and it saw official recognition by the state of Jharkhand in 2007. The Kurukh Literary Society of India has been instrumental in spreading the Tolong Siki script for Kurukh literature.[12][13]

Geographical distribution

- Jharkhand (47.9%)

- Chhattisgarh (26.0%)

- West Bengal (8.65%)

- Odisha (6.84%)

- Bihar (4.43%)

- Assam (3.69%)

- Other (2.51%)

In India, Kurukh is mostly spoken in Raigarh, Surguja, Jashpur of Chhattisgarh, Gumla, Ranchi, Lohardaga, Latehar, Simdega of Jharkhand; Jharsuguda, Sundargarh and Sambalpur district of Odisha.

It is also spoken in Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal, Assam and Tripura states by Kurukh who are mostly Tea-garden workers.[1]

Speakers

It is spoken by 2,053,000 people from the Oraon and Kisan tribes, with 1,834,000 and 219,000 speakers respectively. The literacy rate is 23% in Oraon and 17% in Kisan. Despite the large number of speakers, the language is considered to be endangered.[14] The governments of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh have introduced the Kurukh language in schools with majority Kurukhar students. Jharkhand and West Bengal both list Kurukh as an official language of their respective states.[15] Bangladesh also has some speakers.

Phonology

Vowels

Kurukh has five cardinal vowels. Each vowel has long, short nasalized and long nasalized counterparts.[16]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Low | a |

Consonants

The table below illustrates the articulation of the consonants.[17]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɳ) | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | plain | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | ʔ |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | plain | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | |||

| Fricative | s | (ʃ) | x | h | ||||

| Rhotic | plain | ɾ | ɽ | |||||

| aspirated | ɽʱ | |||||||

| Glide | w | l | j | |||||

- Medially voiced aspirates and voiced plosives + /h/ contrast, there are some minimal pairs like /dʱandha:/ "astonishment" and /dʱandʱa:/ "exertion". Clusters of voiced aspirates and /h/ are possible too as in /madʒʱhi:/ "middle" and /madʒʱis/ "zamindar's agent".[18]

- Of the nasals, /m, n/ are phonemic; [ɳ] only occurs before retroflex plosives; /ŋ/ mostly occurs before other velars but can occur finally with deletion of previous /g/, there are cases where /ŋg/ and /ng/ contrast; /ɲ/ mostly occurs before post alveolars but /j/ can become /ɲ/ around nasal vowels as in /paɲɲa:/ (or /pãjja:/).[19]

Morphology

Kurukh, like other Dravidian languages, is an agglutinative language. The sentence structure is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV). In its morphological construction, there is suffixation but there are no infixes or prefixes. [20]

Nouns

Kurukh nouns have three grammatical genders, namely masculine, feminine and neuter. To the Kurukh only men are masculine ; women and goddesses (evil spirits) are feminine ; all others are neutral. Masculine nouns of the third person singular have two forms, the indefinite and the definite. The indefinite is the simplest form of the noun, thus āl man. The definite form is made by adding -as for the singular, thus ālas, ("the man").[21]

There are only two grammatical numbers, the singular and the plural. [21]

The following is an example declension table for a masculine noun "āl", meaning "man" [22]

| Case | Singular | Definite | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | āl | ālas | ālar |

| Genitive | āl | ālas gahi | ālar gahi |

| Dative | āl | ālas gē | ālar gē |

| Accusative | ālan | ālasin | ālarin |

| Ablative | āltī | ālas tī | ālartī , ālarintī |

| Instrumental | āl trī, āl trū | - | ālar ṭrī, ālar trū |

| Vocative | ē ālayо̄ | - | ē ālarо̄ |

| Locative | āl | ālas nū | ālar nū |

The feminine declension is almost identical to the masculine, but lacks a definite form. The following example is for "mukkā" ("woman"). [22]

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | mukkā | mukkar |

| Genitive | mukkā gahi | mukkar gahi |

| Dative | mukkāgē | mukkar gē |

| Accusative | mukkan | mukkarin |

| Ablative | mukkantī | mukkartī , mukkarintī |

| Instrumental | mukkā trī, mukkā trū | mukkar trī, mukkar trū |

| Vocative | ē mukkai | ē mukkarо̄ |

| Locative | mukkā nū | mukkar nū |

The neuter declension for "allā" ("dog") shows almost identical singular forms, but a difference in pluralization. [22]

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | allā | allā guṭhi |

| Genitive | allā gahi | allā guṭhi gahi |

| Dative | allā gē | allā guṭhi gē |

| Accusative | allan | allā guṭhin |

| Ablative | allantī | allā guṭhi tī , allā guṭhintī |

| Instrumental | allā trī, allā trū | allā guṭhi trī, allā guṭhi trū |

| Vocative | ē allā | ē allā guṭhi |

| Locative | allā nū | allā guṭhi nū |

Education

The Kurukh language is taught as a subject in the schools of Jharkhand, Chhattishgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, West Bengal and Assam.[23]

Sample phrases

| Phrases | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Nighai endra naame? | What is your name? |

| Neen ekase ra'din? | How are you? (Girl) |

| Neen ekase ra'dai? | How are you? (Boy) |

| Een korem ra'dan. | I am fine. |

| Neen ekshan kalalagdin? | Where are you going? (Girl) |

| Neen ekshan kalalagday? | Where are you going? (Boy) |

| Endra manja? | What happened? |

| Ha'an | Yes |

| Malla | No |

| Een mokha Lagdan. | I am eating. |

| Neen mokha. | You eat. |

| Neen ona. | You drink |

| Aar mokha lagnar. | They are eating. |

| Daw makha | Good Night |

Sample text

English

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Devanagari script

होर्मा आलारिन् हक् गहि बारे नू मल्लिन्ता अजादि अरा आण्टें मन्ना गहि हक़् ख़खर्कि रै। आरिन् लुर् अरा जिया गहि दव् बौसा ख़खकि रै अरा तम्है मझि नू मेल्-प्रें गहि बेव्हार् नन्ना चहि।

Latin script

Hōrmā ālārin hak gahi bāre nū mallintā azādi arā aṅṭēm mannā gahi haq xakharki raī. Ārin lur arā jiyā gahi dav bausā xakhakī raī arā tamhai majhi nū mēl-prēm gahi bēvhār nannā nā cahi.

Alternative names and dialects

Kurukh has a number of alternative names such as Uraon, Kurux, Kunrukh, Kunna, Urang, Morva, and Birhor. Two dialects, Oraon and Kisan, have 73% intelligibility between them. Oraon but not Kisan is currently being standardised. Kisan is currently endangered, with a decline rate of 12.3% from 1991 to 2001.[24]

References

- ^ a b c "Kurux". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues - 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ "Kurux, Nepali". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- ^ "Kurukh". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Glottolog 4.5 - Nepali Kurux".

- ^ Evans, Lisa (15 April 2011). "Endangered Languages: The Full List". The Guardian.

- ^ Dalton E. T. The Oraons: Descriptive Ethnology of Bengal. 1872. Section 1, page 215.

- ^ Ferdinand Hahn (1985). Grammar of the Kurukh Language. Mittal Publications. p. xii. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Stassen, Leon (1997). Intransitive Predication. Oxford Studies in Typology and Linguistic Theory. Oxford University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0199258932.

- ^ PS Subrahmanyam, "Kurukh", in ELL2. Ethnologue assigns Nepali Kurux a separate iso code, kxl.

- ^ Mandal, Biswajit. "Kurukh Banna". Omniglot.

- ^ Ager, Simon. "Tolong Siki alphabet and the Kurukh language". Omniglot. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Pandey, Anshuman (8 April 2010). "Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Tolong Siki Script in the UCS" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Daniel Nettle and Suzanne Romaine. Vanishing Voices: The Extinction of the World's Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Page 9.

- ^ "Kurukh given official language status in West Bengal". Jagranjosh.com. 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ Kobayashi & Tirkey 2017, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kobayashi & Tirkey 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Kobayashi & Tirkey (2017), p. 35.

- ^ Kobayashi & Tirkey (2017), p. 36.

- ^ https://rupkatha.com/V9/n2/v9n235.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b "Kurukh grammar". Calcutta Bengal Secretariat Press. 1911.

- ^ a b c "Kurukh grammar". Calcutta Bengal Secretariat Press. 1911.

- ^ Singh, Shiv Sahay (2017-03-02). "Kurukh gets official language status in West Bengal". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ ORGI. "Census of India: Growth of Non-Scheduled Languages-1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

Sources

- Kobayashi, Masato; Tirkey, Bablu (2017). The Kurux Language. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34766-3.

- Kurukh Grammer by the Rev. Ferdiand Hahn

- The Dravadian Languages by Bhadriraju Krishnamurti Grignard's Kurukh Classification.

Further reading

- Andronov, M. S. (1974). "Elements of Kurux Historical Phonology". Anthropos. 69 (1/2). Anthropos Institut: 250–253. ISSN 0257-9774. JSTOR 40458519. Retrieved 5 March 2025.

- Kobayashi, Masato (19 September 2021). "Viewing Proto-Dravidian from the Northeast". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 140 (2). doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.2.0467. ISSN 2169-2289.

- Perumalsamy, P. (2002) "Kisan" in Linguistic Survey of India: Orissa volume, New Delhi: Office of Registrar General, pp: 497-515.

- Folktale collections

- Hahn, Ferdinand. Blicke in die Geisteswelt der heidnischen Kols: Sammlung von Sagen, Märchen und Liedern der Oraon in Chota Nagpur. Gütersloh: C. Bertelsmann, 1906.

- Hahn (1931). A. Grignard (ed.). Hahn's Oraon Folk-lore in the Original: a critical text with translation and notes. Guwahati; Delhi: Spectrum Publications.

External links

- Ferdinand Hahn (1903). Kuruḵh̲ (Orā̃ō)-English dictionary. Bengal Secretariat Press. pp. 126–. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Ferdinand Hahn (1900). Kuruḵẖ grammar. Bengal Secretariat Press. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Kuruk̲h̲ folk-lore: in the original. The Bengal Secretariat Book Depot. 1905. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Kurukh basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Proposal to encode Tolong Siki

- Omniglot's page on Tolong Siki

- Tolong Siki script site