| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Indeterminable | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Spanish and Louisiana Creole | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| African Americans, French, French-Canadian Americans, Cajuns, Creoles of color, Isleños, Haitians (Saint-Domingue Creoles), Québécois, Alabama Creoles, Missouri French |

| Homeland of the Arkansas Creoles under France Colonie de la Louisiane (French) | |

|---|---|

| Haute-Louisuane and Basse-Louisane District of New France | |

[[Flag of France|The Royal Banner of early modern France or "Bourbon Flag"]]

| |

| • Type | Monarchy |

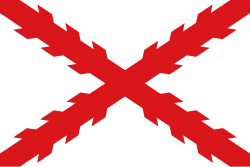

| Homeland of Arkansas Creoles under Spain Provincia de Luisiana (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| Province of New Spain | |

| • Type | Monarchy |

Arkansas Creoles (French: Créole de l'Arkansas, Louisiana Creole: Moun Kréyòl Arkansas, Spanish: Criollos de Arkansas), or Arkansas Metis, are a Louisiana French ethnic group descended from the inhabitants of Colonial New France & French Louisiana, including the Creole Corridor and Arkansas, during the periods of French and Spanish rule, before it became a part of the United States or in the early years under the United States. They share cultural ties such as the traditional use of the French, Spanish, Louisiana French, and Creole languages,[1], and predominantly practice Catholicism.[2]

The term Créole was originally used by French Creoles / French Louisianians to distinguish people born in Louisiana from those born elsewhere, thus drawing a distinction between Old-World Europeans (and Africans) and their descendants born in the New World.[2][3] The word is not a racial label—people of European, African, or mixed ancestry can and have identified as Louisiana Creoles since the 18th century. After the Sale of Louisiana, the term "Creole" took on a more political meaning and identity, especially for those people of Latinate culture. The Catholic Latin-Creole culture in Louisiana contrasted greatly to the Anglo-Protestant culture of Yankee Americans.[4]

Although the terms "Cajun" and "Creole peoples" today are often seen as separate identities, Cajuns have historically been known as Creoles.[5][6] Today, the most famous Creole groups are the Alabama Creoles (including Alabama Cajans), Arkansas Creoles, Louisiana Creoles (including Louisiana Cajuns), and the Missouri French (Illinois Country Creoles). Currently some Arkansans may identify exclusively as either Cajun or Creole, while others embrace both identities.

Creoles of French descent, including those of Québécois or Acadian lineage, have historically comprised the majority of white-identified Creoles in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas. In the early 19th century amid the Haitian Revolution, refugees of both whites and free people of color originally from Saint-Domingue arrived in New Orleans with their slaves having been deported from Cuba, doubled the city's population and helped strengthen its Francophone culture.[7] From there smaller numbers travelled up the Mississippi River, Arkansas River, White River (Arkansas–Missouri), Cache River, Bayou des Arc, Little Red River, Black River, L'Anguille River, St. Francis River, Cossatot River, Saline River, Caddo River, Boeuf River, Antoine River, and Ouachita Rivers. Francophones also lent the names of the mountain ranges in Arkansas upon exploring them. Originally the Ozarks Mountains and Ouachita Mountains, both French names as well, were known as the Masserne or Mazern Mountains, possibly a derivative of the name Mont Cerne. [8]

The first settlement was at Poste de Arkansea (Arkansas Post/Arkansas Post National Memorial) in Southeastern Arkansas, then locations like Cadron (now Conway) in central Arkansas, and Belle Pointe (now Fort Smith, Arkansas) in Western Arkansas, and even more remote locations in Arkansas. Poste de Arkansea, or Akansa or Aux Arc, become one fortified trading location along the Mississippi Creole Corridor along with Vincennes, Kaskaskia, Ste Genevieve, and Cahokia. Later 19th-century immigrants to Arkansas, such as Irish, Germans, and Italians, also married into the Creole group. Most of these immigrants were Catholic.

Historical context

Créole is derived from Latin and means to "create", and was first used in the "New World" by the Portuguese to describe local goods and products. The Spanish later used the term during colonial occupation to mean any native inhabitant of the New World.[9] French colonists used the term Créole to distinguish themselves from foreign-born settlers, and later as distinct from Anglo-American settlers.

Créole referred to people born in Louisiana whose ancestors came from other places. Colonial documents show that the term Créole was used variously at different times to refer to white people, mixed-race people, and black people, both free-born and enslaved.[10] The addition of "-of color" was historically necessary when referring to Creoles of African and mixed ancestry, as the term "Creole" (Créole) did not convey any racial connotation until after the colonial period.[11]

During French colonization, social order was divided into three distinct categories: Creole aristocrats (grands habitants); a prosperous, educated group of multi-racial Creoles of European, African and Native American descent (bourgeoisie); and the far larger class of African slaves and Creole peasants (petits habitants). French Law regulated interracial conduct within the colony. An example of such laws are the Louisiana Code Noir.[12]

Though interracial relations were legally forbidden, or restricted, they were not uncommon. For a time, there were customs regulating relationships between white men and young women of African or mixed ancestry, whose mothers would negotiate the terms. These often included freedom for an enslaved woman and any children of the union, property settlement, and education. Mixed-race Creoles of color became identified as a distinct ethnic group, Gens de couleur libres (free persons of color), and were granted their free-person status by the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1810.[13]

Social markers of creole identity have included being of Catholic faith, being a speaker of French and/or another French-derived language, having a strong work ethic, and being a fan of literature. Many may acquire Louisiana French or Louisiana Creole from familial exposure, but learn Standard French in school,[14] particularly in Louisiana. There has been a revival of French after its systematic suppression for a period by Anglo-Americans.[15] The approach to revitalization is somewhat controversial as many French Louisianians argue the prioritization of Standard French education deprioritizes Louisianisms.[16]

.jpg/440px-Jacques_Amans,_Creole_in_a_red_headdress_(Historic_New_Orleans_Coll_2010.0306).jpg)

For many, being a descendant of the Gens de couleur libres is an identity marker specific to Creoles of color.[14] Many Creoles of color were free-born, and their descendants often enjoyed many of the same privileges that whites did, including (but not limited to) property ownership, formal education, and service in the militia. During the antebellum period, their society was structured along class lines, and they tended to marry within their group. While it was not illegal, it was a social taboo for Creoles of color to marry slaves and it was a rare occurrence. Some of the wealthier and prosperous Creoles of color owned slaves themselves. Many did so to free and/or reunite with once-separated family members.[17] Other Creoles of color, such as Thomy Lafon, used their social position to support the abolitionist cause.

Origin

The Quapaw

The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers, at least by the mid-17th century. The Illinois (Illinois Confederation) and other Algonquian-speaking peoples to the northeast referred to these people as the Akansea or Akansa, referring to geography and meaning "land of the downriver people". As French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet encountered and interacted with the Illinois before they did the Quapaw, they adopted this exonym for the more westerly people. In their language, they referred to them as Arcansas. English-speaking settlers who arrived later in the region adopted the name used by the French, and adapted it to English spelling conventions.

In 1686, at the request of the Quapaw, the French commander Henri de Tonti built a post near the mouth of the Arkansas River, which was later known as the Arkansas Post. This was the very first European settlement along the Mississippi River. This settlement was established at the Quapaw's design and request, primarily because the Quapaw wanted European firearms to use against their enemies who had already received them from the British.[18] Tonti arranged for a resident Jesuit missionary to be assigned there, but apparently without result. About 1697, a smallpox epidemic killed the greater part of the women and children of two villages. In 1727, the Jesuits, from their house in New Orleans, again took up the missionary work.

The Quapaw were staunch allies of the French and backed them in regional conflicts. In 1729, the Quapaw allied with French colonists against the Natchez during the Natchez War, which was also referred to as the Natchez Revolt. This conflict ultimately involved multiple tribes allying with the French against the Natchez, ultimately resulting in the practical extermination of the Natchez tribe. The Quapaw also allied with France during the Chickasaw Wars, which spanned from 1721 to 1763.[18]

The French and Indians influenced each other in many areas. The French settlers in Arkansas learned the languages of the natives, such as Quapaw, which was a Dhegiha Siouan language group closely connected to the Omaha, Ponca, Osage and Kaw/Kansa. This language served as a lingua franca among the French and Indian tribes in the region. The Indians bought European goods (fabric, alcohol, firearms, etc.), learned French, and sometimes adopted their religion.

The French relocated the Arkansas Post upriver, both to avoid flooding and to maintain close proximity to the Quapaw who were also moving up the river for defensive purposes. After France was defeated by the British in the Seven Years' War, it ceded its North American territories to Britain. This nation exchanged some territory with Spain, which took over "control" of Arkansas and other former French territory west of the Mississippi River. The Spanish built new forts to protect its valued trading post with the Quapaw. Relationships with the Spanish were more strained than they had been with France due to a variety of complications. Eventually the Spanish and the Quapaw would come into good terms however, and the Quapaw even signed a treaty during this time.[19][18]

During the early years of colonial rule, many of the ethnic French fur traders and voyageurs had an amicable relationship with the Quapaw, as they did with many other trading tribes.[20] Many Quapaw women and French men cohabitated. Pine Bluff, Arkansas, was founded by Joseph Bonne, a man of Quapaw-French ancestry.

Shortly after the United States acquired the territory in 1803 by the Louisiana Purchase, it recorded the Quapaw as living in three villages on the south side of the Arkansas River about 12 miles (19 km) above Arkansas Post. In 1818. as part of a treaty negotiation, the U.S. government acknowledged the Quapaw as rightful owners of approximately 32 million acres (13 million ha), which included all of present-day Arkansas south and west of the Arkansas River, as well as portions of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Oklahoma from the Red River to beyond the Arkansas and east of the Mississippi.[21] The treaty required the Quapaws to cede almost 31 million acres (13 million ha) of this area to the U.S. government, giving the Quapaw title to 1.5 million acres (0.61 million ha) between the Arkansas and the Saline in Southeast Arkansas. In exchange for the territory, the U.S. pledged $4,000 ($82,000 in today's dollars) and an annual payment of $1,000 ($21,000 in today's dollars).[22] A transcription error in Congress later removed most of Grant County, Arkansas and part of Saline County, Arkansas from the Quapaw claim.[23]

Under continued U.S. pressure, in 1824 they ceded this also, excepting 80 acres (320,000 m2) occupied by the chief Saracen, a French Quapaw creole, below Pine Bluff. They expected to incorporate with the Caddo of Louisiana, but were refused permission by the United States. Successive floods in the Caddo country near the Red River pushed many of the tribe toward starvation, and they wandered back to their old homes.

Sarrasin (alternate spelling Saracen), their last chief before the removal, was a Roman Catholic and friend of the Lazarist missionaries (Congregation of the Missions), who had arrived in 1818. He died about 1830 and is buried adjoining St. Joseph's Church, Pine Bluff. A a memorial window in the church preserves his name. Fr. John M. Odin was the pioneer Lazarist missionary among the Quapaw; he later served as the Catholic Archbishop of New Orleans.

In 1834, under another treaty and the federal policy of Indian Removal, the Quapaw were removed from the Mississippi valley areas to their present location in the northeast corner of Oklahoma, then Indian Territory.

In 1824, the Jesuits of Maryland, under Father Charles Van Quickenborne, took up work among the local and migrant tribes of Indian Territory (present-day Kansas and Oklahoma). In 1846, the Mission of St. Francis was established among the Osage, on Neosho River, by Fathers John Shoenmakers and John Bax. They extended their services to the Quapaw for some years.

First French period

Through both the French and Spanish (late 18th century) regimes, parochial and colonial governments used the term Creole for ethnic French and Spanish people born in the New World. Parisian French was the predominant language among colonists there.

Their dialect evolved to contain local phrases and slang terms. French Creoles spoke what became known as Louisiana French. It was spoken by ethnic religious French and Spanish and the French and Romantics of Creole descent. An estimated 7,000 European immigrants settled in Louisiana in the 18th century, one percent of the French population present at the founding of the United States. There is record of the signing of constitutional agreements in prominent French Creole Plantation Homes. Colonial la Basse-(Lower) Louisiana attracted considerably more Frenchmen due to the presence of the Catholic Church. Most other regions were reached by Protestant missionaries instead.

After enduring a journey of over two months across the Atlantic Ocean, French colonists faced challenges upon reaching the Louisiana (New France) frontier. Living conditions were difficult: they had to face an often hostile environment, including a hot and humid climate and tropical diseases. Many died during the crossing or soon after arrival.

The Mississippi Delta suffered from periodic yellow fever epidemics. Additionally, Europeans introduced diseases like malaria and cholera, which flourished due to mosquitoes and poor sanitation. These challenging conditions hindered the colonization efforts. Furthermore, French settlements and forts could not always provide adequate protection from enemy assaults. Isolated colonists were also at risk from attacks by Indigenous peoples.

In the colonial period, men tended to marry after becoming financially established. French settlers often married Native American and African women, the latter as slaves were imported. Intermarriage created a large multiracial Creole population.

Indentured servants and Casquette girls

Aside from French government representatives and soldiers, colonists included mostly young men. Some labored as engagés (indentured servants); they were required to remain in French Louisiana for a contracted length of service, to pay back the cost of passage and board. Engagés in French Louisiana generally worked for seven years, while their masters provided them housing, food, and clothing.[24][25][26]

Starting in 1698, French merchants were required to transport men to the colonies in proportion to the ships' cargo. Some were bound by three-year indenture contracts.[27] Under John Law and the Compagnie du Mississippi, efforts to increase the use of engagés in the colony were made, notably including German settlers whose contracts became defunct when the company went bankrupt in 1731.[28]

During this time, in order to increase the colonial population, the government recruited young Frenchwomen, filles à la cassette (in English, casket girls, referring to the casket or case of belongings they brought with them), also known as Correction girls and Pelican girls, to travel to the colony and marry colonial soldiers. The king financed dowries for each girl. This practice was similar to events in 17th-century Quebec when about 800 filles du roi (daughters of the king) were recruited to immigrate to New France under the financial sponsorship of Louis XIV.

The system of plaçage that continued into the 19th century resulted in many young white men having women of color as partners and mothers to their children, often before or even after their marriages to white women.[29] French Louisiana also included communities of Swiss and German settlers; however, royal authorities did not refer to "Louisianans" but described the colonial population as "French" citizens.

French Indians in Arkansas

.jpg/440px-Louisiana_Indians_Walking_Along_a_Bayou_-_Alfred_Boisseau_(New_Orleans_Mus_of_Art_56.34).jpg)

New France wished to make Native Americans subjects of the king and good Christians, but the distance from Metropolitan France and the sparseness of French settlement intervened. In official rhetoric, the Native Americans were regarded as subjects of the Viceroyalty of New France, but in reality, they were largely autonomous due to their numerical superiority. The colonial authorities (governors, officers) did not have the human resources to establish French law and customs, and instead often compromised with the locals.

Indian tribes offered essential support for the French: they ensured the survival of New France's colonists, participated with them in the fur trade, and acted as expedition guides.

The French/Indian alliance provided mutual protection from hostile non-allied tribes and incursions on French and Indian land from enemy European powers. The alliance proved invaluable during the later French and Indian War against the New England colonies in 1753.[30]

The coureurs des bois and soldiers borrowed canoes and moccasins. Many ate native food, such as wild rice, bears, and dogs. The colonists were often dependent on Native Americans for food. Creole cuisine is the heir of these mutual influences: thus, sagamité, for example, is a mix of corn pulp, bear fat, and bacon. Gumbo consists primarily of a strongly flavored stock, meat or shellfish (or sometimes both), a thickener, and the Creole "holy trinity": celery, bell peppers, and onions. Today "jambalaya" refers to a number of different of recipes calling for spicy meat and rice. Sometimes medicine men succeeded in curing colonists thanks to traditional remedies, such as the application of fir tree gum on wounds and Royal Fern on rattlesnake bites.

By the 1750s in New France, the Native Americans came under the myth of the Noble Savage, holding that Indians were spiritually pure and played an important role in the New World's natural purity. Indian women were consistently considered to be good wives to foster trade and help create offspring. Their intermarriage created a large métis (mixed French Indian) population.[31]

In spite of disagreements (some Indians killed farmers' pigs, which devastated corn fields) and sometimes violent confrontations (Fox Wars, the relationship with Native Americans was relatively good in colonial Arkansas. French imperialism was expressed through wars and the enslavement of some Native Americans. But most of the time, the relationship was based on dialogue and negotiation.

John Law's Concession

Labor shortages were a pressing issue in French Louisiana. The Royal Indies Company held a monopoly over the slave trade in the area. Law's Company was formally known, first, as the Compagnie d'Occident (lit. 'Company of the West') from August 1717 to May 1719, then as the Compagnie des Indes (lit. 'Company of the Indies'). It was also popularly referred to as the Compagnie du Mississippi (lit. 'Mississippi Company').

In 1717, John Law, the French Comptroller General of Finances, and his company decided to import African slaves there. His objective was to develop the plantation economy of Lower Louisiana. John Law's Company, founded in 1717 by Scottish economist and financier John Law, was a joint-stock company that occupies a unique place in French and European monetary history, as it was for a brief moment granted the entire revenue-raising capacity of the French state. It also absorbed all previous French chartered colonial companies and was popularly known as the Compagnie du Mississippi (Mississippi Company), even though under Law's leadership its overseas operations remained secondary to its domestic financial activity.

In February 1720, the company acquired John Law's Bank, which had been France's first central bank. The experiment was short-lived, and after a stock market collapse of the company's shares in the second half of 1720 (the Mississippi Bubble), the company was placed under government receivership in April 1721. It emerged from that process in 1723 as the French Indies Company, focused on what had been the overseas operations of Law's Company.

The Mississippi Company arranged ships to bring in 800 more settlers, who landed in Louisiana in 1718, doubling the European population. Law encouraged some German-speaking people, including Alsatians and Swiss, to emigrate.

Prisoners were deported from Paris to Mississippi beginning in September 1719, and encouraged by Law to marry young women recruited in hospitals.[32] In May 1720, after complaints from the Mississippi Company and the concessioners about this class of French immigrants, the French government prohibited such deportations. However, there was a third shipment of prisoners in 1721.[33]

The company was involved in the Atlantic slave trade, importing African slaves along the Mississippi River to points as far North as modern Illinois.[34]

The company was at the center of the broader monetary and fiscal scheme known as Law's System (French: le système de Law). Initially the System's main entity was Law's Bank, but the System and the Company became practically synonymous after the Bank was merged into the Company in February 1720.

The company was involved in the Atlantic slave trade, importing African slaves along the Mississippi River to points as far North as modern Illinois.[35]

The market price of company shares eventually reached the peak of 10,000 livres. As the shareholders were selling their shares, the money supply in France suddenly doubled, and inflation burgeoned. Inflation reached a monthly rate of 23% in January 1720.[36] The company further purchased the Banque Royale, in February 1720, and the Compagnie de Saint-Domingue and the monopoly on France's slave trade, in September 1720.[37]: 17

The "bubble" burst at the end of 1720.[36] By September 1720 the price of shares in the company had fallen to 2,000 livres and to 1,000 by December. By September 1721 share prices had dropped to 500 livres, where they had been at the beginning.

By the end of 1720, Philippe d'Orléans had dismissed Law from his positions. Law then fled France for Brussels, eventually moving on to Venice, where his livelihood was gambling. He was buried in the church San Moisè in Venice.[38]

The Company, together with the bank it owned and managed, was placed in receivership in April 1721.[37]: 36 It emerged from that process in March 1723,[37]: 42 , by which time all its operations were in Overseas trading and colonial development. As part of the restructuring, the French state paid the company an indemnity of 514 million livres to make it whole, and it kept its prior shareholders; its trading and navigation privileges were confirmed by a series of royal edicts in June 1725 which closed the restructuring.[39]: 11 It kept operating as the French Indies Company until eventual liquidation in 1770.

Africans in French Louisiana

.tif/lossy-page1-440px-Untitled_Image_(King_of_Loango).tif.jpg)

During the French period about two-thirds of the enslaved Africans brought to Louisiana came from the area that is now Senegambia (which are the modern states of Senegal, Gambia, Mali, and Guinea, Guinea Bissau and Mauritania) . This original population creolized, mixing their African cultures with elements of the French and Spanish colonial society and quickly establishing a Creole culture that influenced every aspect of the new colony.[40]

Most enslaved Africans imported to Louisiana were from modern day Angola, Congo, Mali, and Senegal. The highest number were of Bakongo and Mbundu descent from Angola,[14][41] They were followed by the Mandinka people and Mina (believed to represent the Ewe and Akan peoples of Ghana).[42] Other ethnic groups imported during this period included members of the Bambara, Wolof, Igbo people, Chamba people, Bamileke, Tikar, and Nago people, a Yoruba subgroup.[41][42][43]

Code Noir and Affranchis

The French slavery law, Code Noir, required that slaves receive baptism and Christian education, although many continued to practice animism and often combined the two faiths.[44]

The Code Noir conferred affranchis (ex-slaves) full citizenship and complete civil equality with other French subjects.[44]

French Louisiana slave society generated its own Afro-Creole culture that affected religious beliefs.[45][46] The slaves brought with them their cultural practices, languages, and religious beliefs rooted in spirit and ancestor worship, as well as Catholic Christianity.[47] In the early 1800s, many Creoles from Saint-Domingue also settled in Louisiana and Arkansas, both free people of color and slaves, following the Haitian Revolution on Saint-Domingue, contributing to the two states' creolization.[42][48]

Free People of Color in New France

Free people of color played an important role in the history of New Orleans and the southern area of New France, both when the area was controlled by the French and Spanish, and after its acquisition by the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase.

When French settlers and traders first arrived in these colonies, the men frequently took Native American women as their concubines or common-law wives (see Marriage 'à la façon du pays'). When African slaves were imported to the colony, many colonists took African women as concubines or wives. In the colonial period of French and Spanish rule, men tended to marry later after becoming financially established. Later, when more white families had settled or developed here, some young French men or ethnic French Creoles still took mixed-race women as mistresses, often known as placées.

Popular stereotypes portray such unions as formal, financial transactions arranged between a white man and the mother of the mixed-race mistress.[49] Supposedly, the young woman of mixed European and African ancestry would attend dances known as "quadroon balls" to meet white gentlemen willing to provide for her and any children she bears from their union. The relationship would end as soon as the man married properly. According to legend, free girls of color were raised by their mothers to become concubines for white men, as they themselves once were.[50]

However, evidence suggests that on account of the community's piety[51] by the late 18th century, free women of color usually preferred the legitimacy of marriage with other free men of color.[52] In cases where free women of color did enter extramarital relationships with white men, such unions were overwhelmingly lifelong and exclusive. Many of these white men remained legal bachelors for life. This form of interracial cohabitation was often viewed as no different from the modern conception of a common-law marriage.[53][54]

As in Saint-Domingue, the free people of color developed as a separate class between the colonial French and Spanish and the mass of black slaves. They often achieved education, practiced artisan trades, and gained some measure of wealth; they spoke French and practiced Catholicism. Many also developed a syncretic Christianity. Many were artisans who owned property and their own businesses. They formed a social category distinct from both whites and slaves, and maintained their own society into the period after United States annexation.[55]

Some historians suggest that free people of color made New Orleans the cradle of the civil rights movement in the United States. They achieved more rights than did free people of color or free blacks in the Thirteen Colonies, including serving in the armed militia. After the United States acquired the Louisiana Territory, Creoles in New Orleans and the region worked to integrate the military en masse.[56]

Spanish period

In the final stages of the global Seven Years' War, and North American French and Indian War with the British colonies, New France ceded Louisiana to Spain in the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762), and then formally with the Treaty of Paris (1763). The Spanish were reluctant to occupy the colony, however, and did not do so until 1769. That year, Spain abolished Native American slavery in New Spain. In addition, Spanish liberal manumission policies contributed to the population growth of Creoles of color.

Spanish Louisiana's Creole descendants, who included Affranchis (ex-slaves), free-born blacks, and mixed-race people, known as Creoles of color (gens de couleur libres), were influenced by French Catholic culture. By the end of the 18th century, many Creoles of color were educated and worked in artisanal or skilled trades; many were property owners. Many Creoles of color were free-born, and their descendants enjoyed many of the same privileges as whites while under Spanish rule, including property ownership, formal education, and service in the militia. Indeed, Creoles of color had been members of the militia for decades under both French and Spanish control. For example, around 80 Creoles of color were recruited into the militia that participated in the Battle of Baton Rouge in 1779.[57]

Acadians in Spanish Louisiana

In 1765, during Spanish rule, several thousand Acadians from the French colony of Acadia (now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island) made their way to French Louisiana after they were expelled from Acadia by the British government after the French and Indian War. They settled chiefly in the southwestern Louisiana region now called Acadiana. The governor Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga,[58] eager to gain more settlers, welcomed the Acadians, who became the ancestors of Louisiana's Cajuns. Handfuls of the refugees made their way to Southwestern Arkansas.[59]

2nd French period, the Sale of Louisiana

Spain ceded Louisiana back to France in 1800 through the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso and the Treaty of Aranjuez (1801), although it remained under nominal Spanish control until 1803. Weeks after reasserting control over the territory, Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States in the wake of the defeat of his forces in Saint-Domingue. Napoleon had been trying to regain control of Saint-Domingue following its rebellion and subsequent Haitian Revolution. After the sale, Anglo-Americans migrated to Arkansas. Later European immigrants included Irish, Germans, and Italians.

Refugees from Saint-Domingue in the Louisiana Territory

In the early 19th century, floods of Creole refugees fled Saint-Domingue and poured into the Mississippi Basin. Thousands of refugees, both white and Creole of color, arrived in French Louisiana, sometimes bringing slaves with them. As more refugees entered, those who had first gone to Cuba also arrived.[60] Officials in Cuba deported many of these refugees in retaliation for Bonapartist schemes in Spain.[61]

In the summer of 1809, a fleet of ships from the Spanish colony of Cuba landed in New Orleans with more than 9,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue aboard, having been expelled by the island's governor, Marqués de Someruelos.[62] Small numbers of these refugees made their way into the Arkansas Delta, settling as far up the river as La Petite Roche (now Little Rock) and Cadron (now Conway).

Ark-La-Tex Creoles

Ark-La-Tex Creoles refer to a diverse group of people with a shared French-speaking heritage in the Ark-La-Tex region, which includes parts of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas. Their ancestry is a mix of European (primarily French, secondarily Spanish), Indigenous (like the Quapaw and Caddo Nations), and African peoples, with the Cane River and other northern Louisiana and Southern Arkansas communities being prominent examples. The "Creole" identity in this region is a product of historical intermingling and cultural blending, distinct from other "Creole" identities elsewhere. Their community was connected to a broader "Creole Corridor" of settlements stretching from New Orleans to the Canadian Maritimes, which allowed for migration and cultural exchange.

While the sophisticated Creole society of New Orleans has historically received much attention, the Cane River area in northwest Louisiana—populated chiefly by Creoles of color —also developed its own strong Creole culture. The community's cultural presence and influence persisted well into the 19th century, despite being a minority population in the region. Many modern Ark-La-Tex Creoles have a distinct cultural heritage that includes their history of French language, intermarriage, and a unique cultural identity shaped by the region's colonial past.

Cane River Creoles

While the sophisticated Creole society of New Orleans has historically received much attention, the Cane River (Rivière aux Cannes) area developed its own strong Creole culture. Creole migrants from New Orleans and various ethnic groups, including Africans, Spanish, Frenchmen, and Native Americans, inhabited this region and mixed together in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The community is located in and around Isle Brevelle in lower Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. There are many Creole communities within Natchitoches Parish, including Natchitoches, Cloutierville, Derry, Gorum, and Natchez. Many of their historic plantations still exist.[63] Some have been designated as National Historic Landmarks and are noted within the Cane River National Heritage Area, as well as the Cane River Creole National Historical Park. Some plantations are sites on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.

Isle Brevelle, the area of land between Cane River and Bayou Brevelle, encompasses approximately 18,000 acres (73 km2) of land, 16,000 acres of which are still owned by descendants of the original Creole families. Many of these families share heritage with the Ark-La-Tex creoles of Southwestern Arkansas.

Rivalry between Creoles and Anglo-Americans

The transfer of the French colony to the United States and the arrival of Anglo Americans from New England and Southern United States created a cultural confrontation. Some Americans were reportedly shocked by aspects of the territory's culture: the predominance of the French language and Roman Catholicism (Catholic Church), the class of free Creoles of color, and the enslaved Africans' traditions.

As Creoles of color had received superior rights and education under Spanish and French rule than their Black American counterparts, many of the United States' earliest writers, poets, and civil activists (e.g., Victor Séjour, Rodolphe Desdunes and Homère Plessy) were Creoles. Today, many of these Creoles of color have assimilated into (and contributed to) Black American culture, while some have retained their distinct identity as a subset within the broader African American ethnic group.[64][65][66]

Anglo-Americans classified society into white and black people (the latter associated strongly with the enslaved). Since the late 17th century, children in British colonies took the status of their mothers at birth; therefore, children of enslaved mothers were born into slavery, regardless of their father's race or status; many mixed-race children were born into chattel slavery in the American South.

In the South, free Black people often did not hold the same rights and freedoms as Catholic Creoles of color during French and Spanish rule, including holding office. Upper-class French Creoles thought that many of the arriving Americans were uncouth, especially the Kentucky boatmen (Kaintucks) who regularly visited, steering flatboats down the Mississippi River filled with goods for market. French-speaking hunters and settlers, many of mixed European and indigenous ancestry, some enslaved or formerly enslaved people of African descent, continued to live and work in this region. New French-speakers continued to arrive as well, albeit in comparatively small numbers, even after the Arkansas Territory’s acquisition by the United States and annexation as a territory in 1819 due to the already established creole occupation of the territory.

In 1816, famous Pirate Jean Lafitte travelled through Arkansas as a Spanish spy, exploring the Arkansas River area, including near Little Rock, Arkansas Post, and Pine Bluff, gathering intelligence on American sentiment (notably Creole dislike for Americans) and prospecting for gold, even staying at places like Cadron. He used the name "Captain Hillare" and traveled with a companion, "John Williams" (Latour). This was part of a larger mission for Spain to assess U.S. expansion into Texas and the Louisiana Purchase territory, but highlighted the growing anti-Anglo American sentiment of the existing Creole population. [67]

By the middle of the 19th century Anglo-American prejudices caused most Arkansas Creoles to either assimilate into the predominant Anglo-American culture, move to Louisiana, or take refuge with the relocated Quapaw in Oklahoma. Today few Arkansans firmly identify with the Creole or Metis culture even though Arkansas still holds many French and Anglicized French family names and place names.

Arkansas Creoles Today

In the twentieth century, the gens de couleur libres in Louisiana and Arkansas became increasingly associated with the term Creole, in part because Anglo-Americans struggled with the idea of an ethno-cultural identity not founded in race. One historian has described this period as the "Americanization of Creoles", including an acceptance of the American binary racial system that divided Creoles between white and black. (See Creoles of color for a detailed analysis of this event.) Concurrently, the number of white-identified Creoles has dwindled, with many adopting the Cajun label instead. In 2005, Arkansas officially recognized the American Creole Indian Nation, by way of the Arkansas Department of Education as a "Protected Ethnic Class", ethnically unique unto themselves & their unique historic culture that pre-dates USA acquisition. This has sparked a movement for more Arkansans of Creole Heritage to reclaim the title of Creole, as is exemplified by sites such as the Creole Chronicles, a facebook page chronicling one Southwestern Arkansas Creole woman's journey to reclaim her family heritage, and the Creole Community she has begun to build around herself.

Notable Arkansas Creoles

- Joseph Bonne (Known as the founder of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Creole of Quapaw, French, and Plains Apache descent.)[68]

- Frank Frost (One of the foremost Delta blues harmonica players of his generation, From Auvergne, Arkansas. Died October, 1999)

- Pierre Gibault (1737–1802) was a French Catholic priest active in the Illinois Country and along the Mississippi Valley. He is remembered for supporting American revolutionary forces and for his pastoral work in frontier communities.)[69]

- French Hill (8th generation Arkansas Creole. He is an American businessman and politician serving as the U.S. representative for Arkansas's 2nd congressional district since 2015. He is a member of the Republican Party.)

- Mary John (Marie-Jeanne) (Marie-Jeanne; (died 1857) was a Creole free woman of color at Arkansas Post. She became a successful businesswoman.)

- Scott Joplin (American composer and pianist, dubbed the "King of Ragtime", from Texarkana, Arkansas. Died April, 1917)

- Louis Jordan (American saxophonist, multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and bandleader from Brinkley, Arkansas. Died February 1975)

- Detroit Junior (American blues pianist, vocalist and songwriter from Haynes, Arkansas. Died August, 2005)

- Bobby King (Chicago blues guitarist, singer and songwriter from Jefferson County, Arkansas. Died July, 1983)

- Robert Lockwood Jr. (American Delta blues guitarist from Turkey Scratch, Arkansas. Died November, 2006)

- Rose Marie McCoy (American songwriter from Oneida, Arkansas. Died January, 2015)

- Florence Price ( American classical composer, pianist, organist and music teacher from Little Rock, Arkansas.Died June 1953)

- Marie Francoise Antoinette Petit de Coulange de Vilemont (She was born to Pierre Louis Petit de Coulange[41] and Françoise Gallard de Chamilly.) [70]

French, Spanish, and Creole Surnames in Arkansas

Today there are several French, Spanish, and French/Spanish Creole surnames that are still present in Arkansas, as is noted from original census records and family trees.

French Surnames

- Antoinne

- Barraque

- Bartholomew/Bartolemy

- Billet/Billette

- Bissette, Blanchard

- Boggy/Bogie/Bogy

- Bonne/Bonnie

- Boutin

- Cadron

- Chenault

- Claude

- Coussot/Coussett

- Daigle

- Darden/Dardenne

- Daucier

- De Luce

- Derieusseaux/Desruisseaux

- Duchassin

- Dumond

- Dumas

- Dupree

- Fabre/Favre/La Favre/La Fave

- Flamant

- Francoeur

- Hallier

- Imbeau

- Jardelas

- La Fargue

- La Fourche

- La Grue

- Lajeunesse

- Lamartine

- Langedoque

- Landry

- Larue

- Larquier

- Levesque

- Le Boeuf/Labeff

- Le Mieux

- Macon/Mason

- Marchand/Merchant

- Mathes/Mathis

- Mazarn/Masserne

- Menard

- Moran

- Moreau/Moro

- Notrebe

- Partain/Parton

- Perthuis/Pertuis

- Pineau

- Renaud/Reynauld

- Sevier

- Socié

- Thibault

- Thibodeaux

- Tollette/Tollit

- Tousey

- Tully

- Vallière/Vallier

- Vassuer/Levasseur

- Vaugine

- Villemont

Spanish Surnames

- Delgado

- Dominque/Dominguez

- Gomes/Gomez

- Gutiérrez/Gutiérres

- Hernández/Hernándes

- Ibáñes

- Jiménez/Ximénes

- Lopes/López

- Marín

- Márquez/Márques

- Martínez/Martínes

- Menéndez

- Míguez/Mígues

- Nogues

- Núñes/Núñez

- Ortégo

- Perset

- Pérez

- Prados/Perados

- Ramírez/Ramíres

- Rodríguez/Rodrígues

- Romero

- Ruíz

- Sáenz

- Sánchez/Sánches

- Solis

- Suárez/Suáres

- Vals/Vales/Valez

- Vásquez

- Viator/Villa Torres.

Place Names of French Origin in Arkansas

Source:[71]

- Arkansas (French interpretation for the Illini name for "Quapaw" from aboriginal word meaning "south wind")[72]

- Antoine ("Anthony")[73]

- Aurelle

- Auvergne (a French region)

- Barraque Township (named for French émigré Antoine Barraqué, 19th-century landowner)[74]

- Bauxite[72]

- Bayou Township[74]

- Bayou Bartholomew

- Bayou Corne (Also known as Comey Bayou)

- Bayou de la pelle, ("Lapile Creek" or "Shoveled made Creek")

- Bayou de Loutre ("Otter Creek")

- Bayou des Arc ("creek of the arches")

- Bayou DeView ("Bayou de Veau", "of the calf")

- Bayou Dorcheat

- Bayou La Baume (French surname, from "Josef de la Baume")

- Bayou Macon (also "Bayou Mason")

- Bayou Meto[75]

- Bayou Papillon (french surname) (named for Jacques Papillon, also known as "Bayou Perpillon" or "Lee Creek")

- Beauchamp ("fair" or "beautiful field" or "plain")

- Beaudry

- Bellaire (from "belle aire", beautiful place)

- Belleville ("Beautiful City")

- Bellefonte (maybe from "belle fontaine", beautiful fountain)[72]

- Bodcaw (from "Bodcau" or "Badeaux", French interpretation of Caddo word for "mound")

- Boeuf River ("Beef")[76] ("La Boeuf River")

- Boggy Bayou (from the French surname of "Bogy" or "Bougy")

- Bogy Township (French surname)

- Bois d'Arc (French for "bow wood")

- Bonair (good air)

- Buie (French surname)

- Burdette

- Cache River[76] ("hideaway")

- Cadron Creek ("quadrant")[76] (Also town of Cadron, modern Conway)

- Calumet (The French word for a Native American tobacco pipe)

- Calvin (from the famous French Protestant)

- Cassa Massa (from "Cache a Macon", or "Mason's Hideaway")

- Cassetête (also "Short Mountain", from "tomahawk")

- Champagnolle (meaning a person from Champagne)[76]

- Chancel

- Charivari Creek (also called "Chiver Creek", "hubbub or uproar")

- Chemin Michel Bonne (Known also as "Mitchell Bonne Trace")

- Chenault Island (Huguenot French surname)

- Chicot County (a stump)[76] (also "Lake Chicot")

- Claude (French surname)

- Cloquet

- Cossatot River ("tomahawk")[76]

- Cousart Bayou ("Bayou Cousot", or "Cusotte" named for Francisco Cousot)

- Curia Creek ("cure")

- Dardanelle[77]

- Darcy (French surname)

- Darysaw (corruption of "Desruisseaux", French surname)

- DeGray Lake ("sandstone")[78]

- De Roche ("creek of the rock")

- Deberrie (French surname)

- Decatur

- Deceiper (from "Bayou du Cyprès", or "Cypress Creek")

- Delaplaine ("Of-the-plains", surname)

- Departee ("separated')

- Derrieusseaux Creek (French surname)

- Devue[78]

- Des Arc ("At the bend")[78]

- Dumas (town named after founders French surname)[72]

- Lake Dumond (French surname)

- Ecore Fabre (Also known as "Écore à Fabri", "Ecore" meaning "bluff" and "Fabre/Fabri" being a French surname. Modern Camden, Arkansas)[78]

- Ecores Rouges ("Red Bluffs", location of the 4th Arkansas Post)

- Fayetteville (named for French general, Marquis de La Fayette)[72]

- Fontaine ("Fountain", a surname)

- Fourche ("Pitchfork")

- Fourche à Loup Creek ("Wolf Fork creek")

- Fourche Dumas ("Fourche à Thomas"creek)

- Fourche Island

- Fourche La Fave River

- Fourche Valley

- Franceway (from Francois)

- Francure

- French Rock ("Le Rocher français", also called Big Rock)

- Frenchman's Bayou[79]

- Galla Rock (from "gallets," meaning pebbles)[78]

- Gallatin

- Glaze Creek ("Bayou (de la) Glaise", or "salt-lick creek")

- Glazypeau Mountain (Anglicization of "Glaise à Paul," meaning "Paul's clay pit", or "Paul's salt lick")[80]

- Grand Glaise ("Large Clay")[80]

- Grand Marais ("Great Marsh")

- Grandee Lake ("Lac [Augustin] Grande", French surname)

- Gravette

- Gulpha (Fourche à Calfat "boat caulker creek")

- Guion (named for a railroad conductor of French-Canadian descent)[79]

- Imbeau Bayou (french surname)

- La Fave ("bean")[80]

- La Grue Bayou (the crane)[80]

- La Grue Springs (town)

- Lacrosse[79]

- Ladelle

- Lafayette County

- LaGrange ("the barn" (possibly for the plantation of the Marquis de Lafayette))[79]

- Lamartine (French author Alphonse de Lamartine, also a surname)

- L'Aigle Creek ("the eagle")[80]

- L'Anguille River ("The Eel")[80]

- Lapile ("a pile," or "the pier")[80]

- Larue (the street)

- Latour (the tower)

- Lave Creek

- Levesque ("Bishop", a common French-Canadian surname)

- L'Eau Frais Creek[80] (original French name, l'eau froid, meaning "the cold water.", also called "low freight" today.)

- Le Petite Roche (Little Rock)

- Macon (French city "Mâcon")

- Magnolia (named for the plant, which was named for the botanist Pierre Magnol)[79]

- Mamelle Mt (originally named "Mamelle" (French for "breast"), it is now named Pinnacle Mountain (Arkansas)

- Marais Saline ("saline marsh")[80] (also called "Marie Saline Landing"

- Marche

- Masserne Mountains (from corruption of "Mt Cerne", also known as "Mazarn Mountains, or a specific mountian called "Mt Mazarn")

- Maumee

- Maumelle (breasts)[75]

- Mazarn Creek ("Mt Cerne")

- Menard Bayou 9 french surname0

- Monette

- Mont Sandels

- Montreal (royal mount)

- Moro Bay (feedbag, French surname "Moreau")[75]

- Mount Magazine ("Magasin," meaning barn or warehouse)[80] (Mount Nebo (Arkansas) was also named Mount Magazine originally)

- New Gascony (Gascony, France)

- Ouachita Mountains (French spelling of local tribe, also anglicized to Washita or Wichita)

- Ozan[81] (A corruption of the French, prairie d'ane, "prairie of the donkey.")

- Ozark (phonetic rendering of either aux Arks, "of the Ark(ansas)" or aux Arcs, "of the arches", or possibly aux arcs-en-ciel, "of the rainbows")[81]

- Ozark Mountains as per immediately above[81]

- Palarm (creek and extinct township, A corruption of the French, "place des alarmes".)

- Paris[81]

- Pereogeethe Lake (from "Lac de la Pirogue d'Auguste", also called "pair of geese lake")

- Paroquet

- Partain

- Petit Jean ("Little John" named after a French explorer on the Arkansas River)

- Point DeLuce Bayou (French surname)

- Point Remove (stream and location, A corruption of the French word remous, meaning "eddy.")

- Pollard

- Poteau River (also a mountain, French for "post," "stake," or "pillar.")

- Prairie County ("prairie" or "meadow")

- Rivière Blanche (White River)

- Robe Bayou

- Saline County[82] ("salt")

- Sans Souci (literally without concern)

- Saracen Lake (named for French Creole Saracen)

- Segur (French city)

- Sevier County

- Shinall Mountain (French surname, also called "Chenal Mountain")

- Smackover (Anglicization of chemin couvert, "covered way")[81]

- Soudan

- St. Francis County (county named after the St Francis River)

- Tchemanahaut (stream near Hot Springs, corruption of French "chemin en haut", or "high road."

- Terre Noire (black earth)[82] (also called "Turnwall Creek")

- Terre Rouge (redland or red earth) (also called Carooze Creek)

- Thibault Plantation (French Colonial Hatian surname, from "Saint Domingue")

- Tollette

- Tully

- Urbanette

- Vache Grasse Creek ("Fat Cow" creek)

- Vallier (French surname)

- Vaucluse (French region)

- Vaugine Township (named for Francis Vaugine, 19th-century landowner)

- Vidette

- Villemont (named for Carlos de Villemont, 19th-century landowner)[83]

- Villemont Township (named for Carlos de Villemont, 19th-century landowner)[83]

Place names of Spanish Origin in Arkansas

- Campo de Esperanza (Modern Hopefield, Arkansas, West Memphis, Arkansas) ("field of Hope")

- Diaz (proper name)

- El Dorado (the golden man)

- Havana (Cuban City)

- Ola (misspelling of "hola", hello)

- Casa (house)

- Perla (pearl)

- New Madrid fault line (City in Spain)

References

- ^ As of 2007[update]

- ^ a b Kathe Managan, The Term "Creole" in Louisiana : An Introduction Archived December 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, lameca.org. Retrieved December 5, 2013

- ^ Bernard, Shane K, "Creoles" Archived June 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, "KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana". Multicultural America, Countries and Their Cultures Website. Retrieved February 3, 2009

- ^ Elizabeth Gentry Sayad (2004). A Yankee in Creole Country. United States of America: Virginia Publishing Company. p. 91.

- ^ Landry, Christophe (January 2016). A Creole Melting Pot: the Politics of Language, Race, and Identity in southwest Louisiana, 1918-45 (PhD thesis). University of Sussex.

- ^ Cleaver, Molly Reid (October 16, 2020). "What's the Difference between Cajun and Creole—or Is There One?". Historic New Orleans Collection. Retrieved June 29, 2024.

- ^ Scott, Rebecca J. (November 2011). "Paper Thin: Freedom and Re-enslavement in the Diaspora of the Haitian Revolution" (PDF). Law and History Review. 29 (4): 1062–1063. doi:10.1017/S0738248011000538.

- ^ Morris, Robert Lee. “Ozark or Masserne.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 1, 1943, pp. 39–42. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/40021457. Accessed 1 Dec. 2025.

- ^ "The Creole Community in The United States of America, a story". African American Registry. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Kein, Sybil. Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana's Free People of Color. Louisiana State University Press, 2009, p. 73. ISBN 9780807126011.

- ^ Christophe, Landry (August 2018). "Creole originally meant …". Louisiana: Cultural and Historic Vistas. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "(1724) Louisiana's Code Noir". BlackPast. July 28, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Dubois, Sylvie; Melançon, Megan (2000). "Creole Is, Creole Ain't: Diachronic and Synchronic Attitudes toward Creole Identity in Southern Louisiana". Language in Society. 29 (2): 237–258. doi:10.1017/S0047404500002037. ISSN 0047-4045. JSTOR 4169003. S2CID 144287855.

- ^ a b c Dormon, James H. (1992). "Louisiana's "Creoles of Color": Ethnicity, Marginality, and Identity". Social Science Quarterly. 73 (3): 615–626. ISSN 0038-4941. JSTOR 42863083. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Brasted, Chelsea (August 25, 2021). "Reviving the Cajun dialect". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on May 28, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Barnett, C. Brian. “‘La Francophonie En Louisiane’: Problems and Recommendations to Strengthen the French Immersion Model.” The French Review, vol. 90, no. 1, 2016, pp. 101–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44078091. Accessed 8 Mar. 2024.

- ^ Oakes pp. 47–49.

- ^ a b c Duval, Kathleen (2024). Native Nations: A Millennium in North American. Random House.

- ^ "Treaty between the Quapaw Great Chief and the Commandant of the Arkansas Post, October 15, 1769" (Document). Louisiana State Museum. 1769.

- ^ Havard, Gilles (2003). Histoire de l'Amérique française. Paris: Flamarion.

- ^ Lancaster, Bob (1989). The Jungles of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. p. 40. ISBN 1557281084. OCLC 19321691.

- ^ Key, Joseph (January 18, 2023). "Quapaw". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Central Arkansas Library System. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ "Lancaster" (1989), p. 41.

- ^ Manie Culbertson (1981). Louisiana: The Land and Its People. United States of America: Pelican Publishing. p. 88.

- ^ Melton McLaurin, Michael Thomason (1981). Mobile the life and times of a great Southern city (1st ed.). United States of America: Windsor Publications. p. 19.

- ^ "Atlantic Indentured Servitude". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Mauro, Frédéric (1986). "French indentured servants for America, 1500–1800". In Emmer, P. C. (ed.). Colonialism and Migration; Indentured Labour Before and After Slavery. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Netherlands. pp. 89–90. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4354-4_5. ISBN 978-94-010-8436-9.

- ^ "German Settlers in Louisiana and New Orleans". The Historic New Orleans Collection. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ Joan M. Martin, Plaçage and the Louisiana Gens de Couleur Libre, in Creole, edited by Sybil Kein, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2000.

- ^ Philip J. Deloria, Neal Salisbury (2004). A Companion to American Indian History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 60.

- ^ Alan Taylor (2019). Race and Ethnicity in America: From Pre-contact to the Present [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 81, 82.

- ^ Hardy, James D. Jr. (1966). "The Transportation of Convicts to Colonial Louisiana". The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 7 (3): 207–220. JSTOR 4230908.

- ^ [1] Cat Island: The History of a Mississippi Gulf Coast Barrier Island, by John Cuevas

- ^ Kleen, Michael (2017). Witchcraft in Illinois: A Cultural History. Arcadia. ISBN 9781625858764.

- ^ Kleen, Michael (2017). Witchcraft in Illinois: A Cultural History. Arcadia. ISBN 9781625858764.

- ^ a b Moen, Jon (October 2001). "John Law and the Mississippi Bubble: 1718–1720". Mississippi History Now. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

Law devalued shares in the company in several stages during 1720, and the value of bank notes was reduced to 50 percent of their face value. ... The fall in the price of stock allowed Law's enemies to take control of the company by confiscating the shares of investors who could not prove they had actually paid for their shares with real assets rather than credit. This reduced investor shares, or shares outstanding, by two-thirds.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Veldewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Sheeran, Paul and Spain, Amber. The international political economy of investment bubbles, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004, ISBN 978-0-7546-1997-0, p. 95

- ^ François R. Velde (2016), "What We Learn from a Sovereign Debt Restructuring in France in 1721", Economic Perspectives, 40 (5), Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

- ^ Hall, Gwendolyn M. (1992). Africans in colonial Louisiana: the development of Afro-Creole culture in eighteenth-century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 434. ISBN 9780807119990.

- ^ a b c Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (2005). Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 43, 44, 154, 155. ISBN 978-0807858622. Cite error: The named reference ":1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c "Louisiana: most African diversity within the United States?". Tracing African Roots (in Dutch). September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Nwokeji, G. Ugo; Eltis, David (2002). "Characteristics of Captives Leaving the Cameroons for the Americas, 1822-37". The Journal of African History. 43 (2): 191–210. doi:10.1017/S0021853701008076. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 4100505. S2CID 162111157.

- ^ a b Brasseaux & Conrad 1992.

- ^ "From Benin to Bourbon Street: A Brief History of Louisiana Voodoo". Vice.com. October 5, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ "The True History and Faith Behind Voodoo". FrenchQuarter.com. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (1995). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press. p. 58.

- ^ "The Louisiana Slave Database". www.whitneyplantation.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Lachance, P. (June 1, 2015). "The Strange History of the American Quadroon: Free Women of Color in the Revolutionary Atlantic World". Journal of American History. 102 (1): 233–234. doi:10.1093/jahist/jav240. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Society In America Vol. II., by Harriet Martineau". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Clark, Emily; Gould, Virginia Meacham (2002). "The Feminine Face of Afro-Catholicism in New Orleans, 1727-1852". The William and Mary Quarterly. 59 (2): 409–448. doi:10.2307/3491743. ISSN 0043-5597. JSTOR 3491743.

- ^ Lachance, Paul F. (1994). "The Formation of a Three-Caste Society: Evidence from Wills in Antebellum New Orleans". Social Science History. 18 (2): 211–242. doi:10.1017/S0145553200016990. ISSN 0145-5532. S2CID 147609139.

- ^ Lachance, P. (June 1, 2015). "Review: The Strange History of the American Quadroon: Free Women of Color in the Revolutionary Atlantic World". Journal of American History. 102 (1): 233–234. doi:10.1093/jahist/jav240. ISSN 0021-8723.

- ^ Wilson, Carol (May 4, 2014). "Plaçage and the Performance of Whiteness: The Trial of Eulalie Mandeville, Free Colored Woman, of Antebellum New Orleans". American Nineteenth Century History. 15 (2): 187–209. doi:10.1080/14664658.2014.959818. ISSN 1466-4658. S2CID 145334891.

- ^ "French Speaking 'Hommes de Couleur Libre' Left Indelible Mark on the Culture and Development of the French Quarter". New Orleans French Quarter. Retrieved September 4, 2024.

- ^ Eaton, Fernin. "Louisiana's Free People of Color-Digitization Grant-letter in support". Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Gayarré, Charles (1867). History of Louisiana ... W. J. Widdleton.

- ^ Cazorla-Granados, Francisco J. (2019). El gobernador Luis de Unzaga (1717–1793) : precursor en el nacimiento de los EE.UU. y en el liberalismo. Frank Cazorla, Rosa María García Baena, José David Polo Rubio. Málaga: Fundación Málaga. pp. 49, 52, 62, 74, 83, 90, 150, 207. ISBN 978-84-09-12410-7. OCLC 1224992294.

- ^ Brasseaux, Carl A. (1992). Acadian to Cajun: Transformation of a People, 1803-1877. Jackson : University Press of Mississippi. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-87805-582-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Dodson, Howard; Diouf, Sylviane Anna (2004). In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience. National Geographic Society. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7922-7385-1.

- ^ Gitlin, Jay (2009). The Bourgeois Frontier: French Towns, French Traders, and American Expansion. Yale University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-300-15576-1.

- ^ Francis Andrew McMichael (2008). Atlantic Loyalties: Americans in Spanish West Florida, 1785-1810. University of Georgia Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8203-3650-3.

- ^ "Cane River Creole Community-A Driving Tour" Archived March 31, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Louisiana Regional Folklife Center, Northwestern State University. Retrieved February 3, 2009

- ^ Steptoe, Tyina (December 15, 2015). "When Louisiana Creoles Arrived in Texas, Were They Black or White?". Zócalo Public Square. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Creole People in America, a brief history". African American Registry. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Beyoncé, Creoles, and Modern Blackness". UC Press Blog. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Jean Laffite's Espionage Mission".

- ^ Morris S. Arnold, “The Métis People of Eighteenth-and Nineteenth-Century Arkansas,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 57, no. 3 (2016): 261–96.

- ^ Morris Arnold, Colonial Arkansas, 1686-1804: A Social and Cultural History

- ^ Arnold, Morris S. (2017). "Colonial Arkansas Women". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 76 (1): 1–3 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Branner, John C. “Some Old French Place Names in the State of Arkansas.” Modern Language Notes 14, no. 2 (1899): 33–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/2917686.

- ^ a b c d e Coulet du Gard & Coulet du Gard 1974, p. 13.

- ^ Branner 1899, p. 34.

- ^ a b Branner 1899, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Branner 1899, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f Branner 1899, p. 36.

- ^ Branner 1899, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c d e Branner 1899, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Coulet du Gard & Coulet du Gard 1974, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Branner 1899, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e Coulet du Gard & Coulet du Gard 1974, p. 16.

- ^ a b Branner 1899, p. 40.

- ^ a b HalliBurton 1903, p. 47.

Sources

- Branner, John C. (February 1899). "Some Old French Place Names in the State of Arkansas" (PDF). Modern Language Notes. xiv (2). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press: 35. doi:10.2307/2917686. JSTOR 2917686. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- Brasseaux, Carl A.; Conrad, Glenn R., eds. (1992). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees, 1792–1809. Lafayette, Louisiana: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana. ISBN 0-940984-76-8. OCLC 26661772.

- Coulet du Gard, René; Coulet du Gard, Dominique (1974). The Handbook of French Place Names in the U.S.A. Chicago: Adams Press.

- HalliBurton, W. H. (1903). A Topographical Description and History of Arkansas County, Arkansas, from 1541 to 1875. History of Arkansas County, Arkansas, 1541-1875. p. 47. hdl:2027/wu.89072963770. OCLC 5815561. Retrieved January 19, 2025 – via HathiTrust.