| Black Death | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Bubonic plague |

| Location | Eurasia and North Africa[1] |

| Date | 1346–1353 |

Deaths | 25,000,000 – 50,000,000 (estimated) |

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as 50 million people[2] perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th-century population.[3] The disease is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread by fleas and through the air.[4][5] One of the most significant events in European history, the Black Death had far-reaching population, economic, and cultural impacts. It was the beginning of the second plague pandemic.[6] The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history.

The origin of the Black Death is disputed.[7] Genetic analysis suggests Yersinia pestis bacteria evolved approximately 7,000 years ago, at the beginning of the Neolithic,[8] with flea-mediated strains emerging around 3,800 years ago during the late Bronze Age.[9] The immediate territorial origins of the Black Death and its outbreak remain unclear, with some evidence pointing towards Central Asia, China, the Middle East, and Europe.[10][11] The pandemic was reportedly first introduced to Europe during the siege of the Genoese trading port of Kaffa in Crimea by the Golden Horde army of Jani Beg in 1347. From Crimea, it was most likely carried by fleas living on the black rats that travelled on Genoese ships, spreading through the Mediterranean Basin and reaching North Africa, West Asia, and the rest of Europe via Constantinople, Sicily, and the Italian Peninsula.[12] There is evidence that once it came ashore, the Black Death mainly spread from person-to-person as pneumonic plague, thus explaining the quick inland spread of the epidemic, which was faster than would be expected if the primary vector was rat fleas causing bubonic plague.[13][14][15] In 2022, it was discovered that there was a sudden surge of deaths in what is today Kyrgyzstan from the Black Death in the late 1330s; when combined with genetic evidence, this implies that the initial spread may have pre-dated, by nearly two decades, the 14th-century Mongol conquests previously postulated as the cause.[16][17]

The Black Death was the second great natural disaster to strike Europe during the Late Middle Ages (the first one being the Great Famine of 1315–1317) and is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of the European population, as well as approximately 33% of the population of the Middle East.[18][19][20] There were further outbreaks throughout the Late Middle Ages and, also due to other contributing factors (the crisis of the late Middle Ages), the European population did not regain its 14th century level until the 16th century.[a][21] Outbreaks of the plague recurred around the world until the early 19th century.

Names

European writers contemporary with the plague described the disease in Latin as pestis or pestilentia, 'pestilence'; epidemia, 'epidemic'; mortalitas, 'mortality'.[22] In English prior to the 18th century, the event was called the "pestilence" or "great pestilence", "the plague" or the "great death".[22][23][24] Subsequent to the pandemic "the furste moreyn" (first murrain) or "first pestilence" was applied, to distinguish the mid-14th century phenomenon from other infectious diseases and epidemics of plague.[22]

The 1347 pandemic plague was not referred to specifically as "black," at the time, in any European language. The expression "black death" had occasionally been applied to other fatal or dangerous diseases.[22] In English, "Black death" was not used to describe this plague pandemic, however, until the 1750s; the term is first attested in 1755, where it translated Danish: den sorte død, lit. 'the black death'.[22][25]

This expression — as a proper name for the pandemic — had been popularized by Swedish and Danish chroniclers in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was transferred to other languages as a calque: Icelandic: svarti dauði, German: der schwarze Tod, and French: la mort noire.[26][27] Previously, most European languages had named the pandemic a variant or calque of the Latin: magna mortalitas, lit. 'Great Death'.[22]

The phrase 'black death' – describing Death as black – is very old. Homer used it in the Odyssey to describe the monstrous Scylla, with her mouths "full of black Death" (Ancient Greek: πλεῖοι μέλανος Θανάτοιο, romanized: pleîoi mélanos Thanátoio).[28][26] Seneca the Younger may have been the first to describe an epidemic as 'black death', (Latin: mors atra) but only in reference to the acute lethality and dark prognosis of disease.[29][26][22] The 12th–13th century French physician Gilles de Corbeil had already used atra mors to refer to a "pestilential fever" (febris pestilentialis) in his work On the Signs and Symptoms of Diseases (De signis et symptomatibus aegritudium).[26][30] The phrase mors nigra, 'black death', was used in 1350 by Simon de Covino (or Couvin), a Belgian astronomer, in his poem "On the Judgement of the Sun at a Feast of Saturn" (De judicio Solis in convivio Saturni), which attributes the plague to an astrological conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn.[31] His use of the phrase is not connected unambiguously with the plague pandemic of 1347 and appears to refer to the fatal outcome of disease.[22]

The historian Elizabeth Penrose, writing under the pen-name "Mrs Markham", described the 14th-century outbreak as the "black death" in 1823.[32] The historian Cardinal Francis Aidan Gasquet wrote about the Great Pestilence in 1893[33] and suggested that it had been "some form of the ordinary Eastern or bubonic plague".[34][b] In 1908, Gasquet said use of the name atra mors for the 14th-century epidemic first appeared in a 1631 book on Danish history by J. I. Pontanus: "Commonly and from its effects, they called it the black death" (Vulgo & ab effectu atram mortem vocitabant).[35][36]

Previous plague epidemics

Research from 2017 suggests plague first infected humans in Europe and Asia in the Late Neolithic-Early Bronze Age.[38] Research in 2018 found evidence of Yersinia pestis in an ancient Swedish tomb, which may have been associated with the "Neolithic decline" around 3000 BCE, in which European populations fell significantly.[39][40] This Y. pestis may have been different from more modern types, with bubonic plague transmissible by fleas first known from Bronze Age remains near Samara.[41]

The symptoms of bubonic plague are first attested in a fragment of Rufus of Ephesus preserved by Oribasius; these ancient medical authorities suggest bubonic plague had appeared in the Roman Empire before the reign of Trajan, six centuries before arriving at Pelusium in the reign of Justinian I.[42] In 2013, researchers confirmed earlier speculation that the cause of the Plague of Justinian (541–549 CE, with recurrences until 750) was Y. pestis.[43][44] This is known as the first plague pandemic. In 610, the Chinese physician Chao Yuanfang described a "malignant bubo" "coming in abruptly with high fever together with the appearance of a bundle of nodes beneath the tissue."[45] The Chinese physician Sun Simo who died in 652 also mentioned a "malignant bubo" and plague that was common in Lingnan (Guangzhou). Ole Jørgen Benedictow believes that this indicates it was an offshoot of the first plague pandemic which made its way eastward to Chinese territory by around 600.[46]

14th-century plague

Causes

Early theory

A report by the Medical Faculty of Paris stated that a conjunction of planets had caused "a great pestilence in the air" (miasma theory).[47] Muslim religious scholars taught that the pandemic was a "martyrdom and mercy" from God, assuring the believer's place in paradise. For non-believers, it was a punishment.[48][page needed] Some Muslim doctors cautioned against trying to prevent or treat a disease sent by God. Others adopted preventive measures and treatments for plague used by Europeans. These Muslim doctors also depended on the writings of the ancient Greeks.[49][50]

Predominant modern theory

Due to climate change in Asia, rodents began to flee the dried-out grasslands to more populated areas, spreading the disease.[51] The plague disease, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, is enzootic (commonly present) in populations of fleas carried by ground rodents, including marmots, in various areas, including Central Asia, Kurdistan, West Asia, North India, Uganda, and the western United States.[52][53]

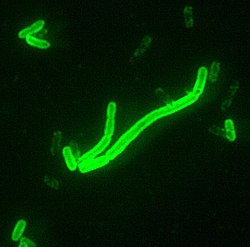

Y. pestis was discovered by Alexandre Yersin, a pupil of Louis Pasteur, during an epidemic of bubonic plague in Hong Kong in 1894; Yersin also proved this bacterium was present in rodents and suggested the rat was the main vehicle of transmission.[54][55] The mechanism by which Y. pestis is usually transmitted was established in 1898 by Paul-Louis Simond and was found to involve the bites of fleas whose midguts had become obstructed by replicating Y. pestis several days after feeding on an infected host.[56] This blockage starves the fleas, drives them to aggressive feeding behaviour, and causes them to try to clear the blockage via regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria flushing into the feeding site and infecting the host. The bubonic plague mechanism was also dependent on two populations of rodents: one resistant to the disease, which act as hosts, keeping the disease endemic, and a second that lacks resistance. When the second population dies, the fleas move on to other hosts, including people, thus creating a human epidemic.[34]

DNA evidence

Definitive confirmation of the role of Y. pestis arrived in 2010 with a publication in PLOS Pathogens by Haensch et al.[4][c] They assessed the presence of DNA/RNA with

.jpg/440px-Xenopsylla_chepsis_(oriental_rat_flea).jpg)