美術におけるヌードの歴史的発展は、世界で時を経て次々と現れた様々な社会や文化におけるヌードの受容の仕方の違いから生じる小さな特殊性を除けば、一般的な美術史と並行して進んでいます。ヌードは、様々な美術媒体(絵画、彫刻、最近では映画や写真)で表現された裸の人体からなる芸術ジャンルです。美術作品の学術的分類の 1 つとされています。美術におけるヌードは一般に、作品が制作された時代の美学や道徳に関する社会的基準を反映しています。多くの文化では、現実のヌードよりも美術におけるヌードの方が寛容度が高く、何が許容されるかについての基準は異なります。たとえば、ヌード作品が展示されている美術館であっても、来館者のヌードは一般に受け入れられません。ヌードは、形式的、美的、図像的に多様なバリエーションがあるため、ジャンルとして取り組むのが複雑な主題であり、美術史家の中には、西洋美術史上最も重要な主題と考える人もいます。[注1]

ヌードは一般的にエロティシズムと結び付けられますが、神話から宗教、解剖学研究など、様々な解釈や意味を持つことがあります。また、古代ギリシャのように、美や美的理想の完璧さの象徴として捉えられることもあります。ヌードの表現は、時代や民族の社会的・文化的価値観によって様々であり、ギリシャ人にとって肉体は誇りの源であったのと同様に、ユダヤ人、そしてキリスト教にとって、肉体は恥の源であり、奴隷や貧困者の身分を表すものでした。[1]

人体の研究と芸術的表現は、先史時代 (ヴィレンドルフのヴィーナス) から現代に至るまで、芸術の歴史を通じて一貫している。裸婦の芸術的表現が最も盛んだった文化の一つは古代ギリシャで、裸婦は完璧で絶対的な美の理想と考えられ、この概念は今日まで古典芸術の中に残り、西洋社会の裸婦や芸術全般に対する認識を大きく左右している。中世では、裸婦の表現は宗教的なテーマに限られ、常にそれを正当化する聖書の一節に基づいていた。ルネサンスでは、より人間中心的な新しい人文主義文化が、芸術への裸婦の復活を促し、一般的には神話や歴史的なテーマに基づき、宗教的なテーマは残された。19世紀、特に印象派の時代になると、裸婦は図像的特徴を失い始め、単にその美的性質のためだけに、官能的で完全に自己言及的なイメージとして表現されるようになった。近年、芸術ジャンルとしてのヌードに関する研究は、記号論的分析、特に作品と鑑賞者の関係性、そしてジェンダー関係の研究に焦点が当てられています。フェミニズムは、ヌードを女性の身体の客体化であり、西洋社会における家父長制的支配の象徴であると批判してきました。ルシアン・フロイドやジェニー・サヴィルといった芸術家は、ヌードの伝統的な概念を排除し、美やジェンダーの概念を超えた本質を探求するために、非理想化されたタイプのヌードを考案しました。[2]

理論的な区別:ヌードと裸

芸術ジャンルとしてのヌードは、歴史的・文化的価値観だけでなく、特に「ヌード」と「裸」の区別に関する理論的解釈の進化によっても形作られてきました。ヌードと裸はしばしば混同されますが、美術史においてはそれぞれ異なる概念を表しています。イギリスの美術史家ケネス・クラークは著書『ヌード:理想形態の研究』の中で、「裸になるということは衣服を脱ぐことであり、その言葉は、私たちのほとんどがその状態で感じる恥ずかしさを暗示しています。一方、『ヌード』という言葉は、教養ある用法においては、不快な意味合いを帯びていません」と述べています。 [3]クラークは「ヌードは芸術の主題ではなく、芸術の一形態である」と主張し、人間の身体は、単に実物を再現するのではなく、芸術家がそれを理想化し、完璧に描写することによって「ヌード」になると主張しました。[3]

ジョン・バーガーは後に『見ることの方法』の中でこの区別を批判し、「裸の身体はヌードになるためには、物体として見られなければならない」と主張した。[4]バーガーにとって「ヌード」とは、特にジェンダーとの関係において、身体を展示と権力構造の対象として位置付ける文化的枠組みを反映している。フランシス・ボルゼロは『裸のヌード』の中でこの考えを拡張し、「裸のヌード」という概念を提示した。これは、脆弱性と美的伝統を融合させたものである。[5]「裸のヌード」を例示する例としては、シャンタル・ジョッフェ、アリス・ニール、ルシアン・フロイドの自画像が挙げられる。これらの作品は、脆弱性と美的伝統の交差を浮き彫りにし、身体を個人的かつ政治的なものとして提示している。この再定義は、身体を個人的、政治的、そして感情的な表現の場として強調し、従来の理想化された完璧さの概念を超えている。

先史時代

先史時代の美術は、石器時代(後期旧石器時代、中石器時代、新石器時代)から金属器時代にかけて発展した美術であり、人類が芸術的とみなせる最初の表現が現れた時代です。旧石器時代(紀元前2万5000~8000年)には、人類は狩猟と洞窟生活を送り、洞窟壁画を制作しました。新石器時代(紀元前6000~3000年)には、人類は農業を発達させ、宗教が重要視されるようになり、手工芸品の生産が始まるなど、社会はますます複雑化しました。金属器時代(紀元前3000~1000年)には、最初の先史時代の 文明が出現しました。[6]

旧石器時代の美術では、裸婦は豊穣の崇拝と強く結びついており、ヴィーナス像に代表される。そのほとんどはオーリニャック文化期のもので、一般的に石灰岩、象牙、滑石で彫られている。ヴィレンドルフ、レスピューグ、マントン、ローセルなどのヴィーナス像が目立つ。男性においては、セルネ・アバスの巨人(イギリス、ドーセット)に見られるように、勃起した男根を単独で、あるいは全身で表現することも豊穣の象徴であった。 [7]洞窟壁画、特にフランス=カンタブリア地方やレヴァント地方で発達したものでは、狩猟場面や儀式や舞踏の場面がよく描かれ、棒人間に簡略化された人物像には性器が強調されて描かれることがある。エル・コグル、バルトルタ、アルペラの洞窟でその例がいくつか発見されている。[8]

古代美術

これは歴史の第一段階における芸術的創造、特に近東の偉大な文明、すなわちエジプトとメソポタミアに与えられた名称です。また、あらゆる大陸のほとんどの民族と文明における初期の芸術的表現も含まれます。この時代における大きな進歩の一つは、主に経済的・商業的な記録を残す必要性から生まれた文字の発明でした。[9]

シュメールからエジプトに至る古代宗教では、古代の母なる大地崇拝は新たな擬人化された神々と関連付けられており、生命の発生源である自然と女性の姿を結びつけていた。例えば、エジプトの双子神ゲブとヌトは大地と空を象徴し、その結合からすべての要素が生まれた。他のケースでは、神々は宇宙論的な要素と関連付けられており、例えば女神イシュタルは金星と結びつき、一般的に裸で翼を持ち、頭に三日月を乗せた姿で表現されている。母なる女神の他の表現は通常、多かれ少なかれ服を着ているが、胸は露出しており、例えば紀元前1550年頃のミノア文明の小像である有名な蛇の女神(イラクリオン考古学博物館)がそうだ。これらの表現は、アルテミス、ダイアナ、デメテル、ケレスといったギリシャ・ローマの女神の図像学の出発点となった。[10]

エジプトでは、裸は自然なことであり、宮廷の場面、特に舞踏や祝宴、お祝いの場面の表現に豊富に見られる。また、宗教的な主題にも存在し、擬人化された神々の多くは、彫像や壁画の中で裸または半裸で登場する。ルーブル美術館の有名な「書記座像」のように、ファラオであれ奴隷であれ、軍人であれ公務員であれ、人間自身の表現にも裸は見られる。間違いなく気候によるものだが、エジプト人は薄着で、男性は腰布とスカート、女性は透け感のある麻のドレスを着ていた。これは、宮廷の祝祭や儀式を描いた場面から、農民、職人、羊飼い、漁師、その他の職業の日常労働を描いたより一般的な場面まで、芸術に反映されている。同様に、戦争場面では、奴隷や捕虜の痛ましい裸体が登場し、正面からの描写が支配的で、身体は硬直した静的な姿勢に拘束され、写実性に欠ける、エジプト美術特有の神聖主義的なスタイルとダイナミズムの欠如で描かれている。この絵画は主に、階層的な基準に従い、重ね合わせた平面に人物を並置して提示していることが特徴である。横顔の規範が主流で、頭と手足は横顔で、肩と目は正面から描かれている。古代エジプトから現代に伝わる作品の中には、部分的または完全な裸体が絵画と彫刻の両方で見られ、記念碑的なものでも、ルーブル美術館の「献金者」や大英博物館の「竪琴を弾く少女」などの小さな彫像でも見られる。私たちには、ラーホテプとノフレト、メンカウラー王(ミケリヌス)と王妃、ルーヴル美術館のトゥイ夫人といった彫像があります。これらの彫像は、亜麻布をまとっているにもかかわらず、布地の透明性によって裸体であることが示されています。絵画では、トトメス4世の会計官ナスの墓の壁画や、サッカラの医師の墓の壁画が見られます。ツタンカーメンの墓からは、ハトホル女神の息子イヒを表わしたファラオの裸像が発見されました。[11]

一方、古代エジプトに地理的にも年代的にも近いメソポタミアでは、裸体画は事実上知られていない。ただし、アッシュールバニパルの獅子狩り(大英博物館所蔵)のようなアッシリアのレリーフでは、王が裸の胴体で描かれている。また、囚人の拷問場面もいくつか見られる。一方、女性の裸体画は、ルーヴル美術館所蔵のカルデアの青銅像(若いカナエフォラを描いたもの)にのみ見られる。モーセの律法によって人間の描写が禁じられていたフェニキア美術やユダヤ美術にも、裸体は見られない。 [12]

古典芸術

古典芸術[注2]は古代ギリシャとローマで発展した芸術であり、その科学的、物質的、美的進歩は芸術の歴史に自然と人間に基づいたスタイル、調和とバランス、形態と量の合理性、そして自然の模倣(「ミメーシス」)の感覚が支配的であったことに貢献し、西洋芸術の基礎を築き、西洋文明の歴史を通じて古典的な形式への回帰が絶えず続いている。[13]

ギリシャ

西洋美術の発展を特徴づける主要な芸術的表現は、ギリシャで発展した。ミノア文化とミケーネ文化の始まりの後、ギリシャ美術はアルカイック、古典期、ヘレニズム期の3つの時期に発展した。自然主義と、寸法と比率における理性の使用、そして自然に触発された美的感覚を特徴とするギリシャ美術は、ヨーロッパ大陸で発展する美術の出発点となった。[14]ギリシャ美術の絶頂期は、いわゆるペリクレスの時代に訪れ、その時代の美術は大きな輝きを放ち、現実を解釈するスタイルを生み出した。芸術家たちは、必要に応じて短縮法に頼りながら、鑑賞者が現実を捉えることができる比率と規則(κανών、カノン)に従って自然を基に作品を制作した。美の概念は自然の模倣に基づいて追求されましたが、肉体と魂の調和を反映した主観的なビジョンを取り入れることで理想化され、美は善(καλοκαγαθία、kalokagathía)と同一視されました。[15]

_MET_DT263.jpg/440px-Marble_statue_of_a_kouros_(youth)_MET_DT263.jpg)

ギリシャは、以前の文化の階層主義や図式化から遠く離れた、自然主義的な方法で人体を表現した最初の場所でした。ギリシャ文化は人文主義的で、彼らの宗教は崇拝の対象というよりは神話的であったため、人間は彼らの哲学と芸術の主な研究対象でした。ギリシャ人にとって、美の理想は男性の裸体であり、裸で競技するオリンピックの選手のように、若さと男らしさを象徴していました。ギリシャのヌードは自然主義的であると同時に理想化されていました。体の各部分を忠実に表現するという点では自然主義的でしたが、調和のとれたバランスのとれたプロポーションの追求という点では理想化されており、体の欠陥や加齢によるしわを示すようなより現実的なタイプの表現は拒否されました。古代のより図式的な構成から、人体の研究は、骨格と筋肉、および人体がとることができる動きとさまざまな姿勢やひねりのより詳細な説明へと進化しました。顔の描写や心の状態の表現も完成された。[16]

ギリシャ人は裸体を非常に重視し、誇りとしていました。なぜなら、裸体は肉体の健康の反映であるだけでなく、美徳と誠実さの象徴であり、他の文明の遅れた民族の抑制とは対照的に、社会進出の要素でもあったからです。ギリシャ人にとって裸体は誠実さの表現であり、人間全体に関わるいかなるものも、避けたり切り離したりすることはできませんでした。彼らは肉体と精神を結びつけました。両者は彼らにとって不可分に結びついており、彼らの宗教心さえも擬人化された神々に具現化されるほどでした。彼らは一見相反する要素を結びつけ、数学のような抽象的なものが感覚的な快楽をもたらすのと同じように、肉体のような物質的なものが霊妙で不滅なものの象徴となることもありました。このように、裸体には単なる官能主義を避ける道徳的な要素があり、ローマ人のように猥褻なものや退廃的なものとは捉えられませんでした。この肉体と精神の相互関係はギリシャ美術に固有のものであり、後世の芸術家たちがギリシャの裸体を模倣したとき、新古典主義やアカデミズムのようにこの要素が取り除かれ、肉体の完璧さに重点を置いたが道徳的な美徳のない、生気のない作品を生み出した。[17]

ギリシャの男性ヌードにおいては、エネルギーと生命力を捉えることが不可欠であり、彼らはそれをアスリートとヒーローという二種類の男性的なヌードを通して表現した。オリンピックでは、優勝者に「パナシナイコ・アンフォラ」と呼ばれる陶器の花瓶を贈るのが慣例であった。この花瓶には、優勝者が駆使した競技の技が表現されており、これは躍動感あふれるアクションシーンにおけるヌード表現の好例である。[18]

男性ヌードの最初の代表作は、アルカイック期(紀元前7世紀~5世紀)に属する、運動選手、神々、あるいは神話の英雄を象ったクーロス(複数形はクーロイ)と呼ばれる像です。女性版はコーレ(複数形はコライ)ですが、こちらは服を着た姿を象っていました。これらの像は元々エジプトの影響をある程度受けていますが、ギリシャの彫刻家たちはすぐに独自の道を歩み、理想の美を表現するために人体を表現する最良の方法を模索しました。クーロスは、正面を向いた神聖体的な姿勢を特徴としています。両足は地面に着き、左足を前に出し、両腕は体に密着し、手は閉じられています。立方体の頭部には長いたてがみがあり、顔の特徴は簡素で、「アルカイック・スマイル」と呼ばれる特徴的な微笑みを際立たせています。最初の例は紀元前7世紀に遡り、デロス島、ナクソス島、サモス島などの地で発見され、一般的には墓や礼拝所に現れました。後にアッティカやペロポネソス半島にも広がり、そこではより写実的な表現が見られるようになり、描写的な特徴と造形への関心が高まりました。今日まで残っている作品には、スニオンのクーロス(紀元前600年)、クレオビスとビトンの双子像(紀元前600年~590年)、モスコフォロス(紀元前570年)、ランピンの騎手像(紀元前550年)、テネアのクーロス(紀元前550年)、アナフィのクーロス(紀元前530年)、アリストディコスのクーロス(紀元前500年)などがあります。[19]

その後、裸婦像は、クーロイの硬直した幾何学的形状から古典期(紀元前490年から紀元前450年の間に発達した厳格な様式)の柔らかく自然な線へと、ゆっくりだが着実に進化した。この革新の主な要因は、理想化から模倣への移行という、彫刻を構想する際の新しい概念であった。この変化は、紀元前5世紀初頭に、ピオンビーノのアポロ(紀元前 490年頃)、クリティオスのエフェベ(紀元前 480年頃) 、ハルモディオスとアリストゲイトンを代表するティラニキデス・グループ(クリティオスとネシオテスの作品、紀元前 477年頃)などの作品で気づき始めた。これらの作品では、肉体的完全性の崇拝が示されており、それは主に運動能力において表現され、肉体的な活力と道徳的美徳および宗教心とが組み合わされていた。新しい古典様式は、人体に動きを与えることで、形式的な自然さだけでなく、生命力に満ちた自然さももたらしました。特に、一般的にクリティオスに帰せられるコントラポストの導入によって、身体の各部分が調和的に対置され、人物像にリズムとバランスがもたらされました。こうした前提のもと、ミュロン、ペイディアス、ポリュクレイトス、プラクシテレス、スコパス、リュシッポスといった古典ギリシャ彫刻の主要な人物像が誕生しました。[20]

ミュロンはディスコボロス(紀元前450年)で、初めて人物像全体の調和のとれたダイナミックな効果を実現し、見事な動的な人物像の例を作った。それまでは、動的な人物像は部分的に作られ、ダイナミックな動きに一貫性をもたらす全体的な視点がなかった。例えば、紀元前470年頃のアッティカ起源の青銅像、アルテミシオン岬のポセイドンでは、胴体は静止しており、腕の動きに追従していない。[21]

ペイディアスは神々の彫刻に特に力を入れ、「神々の創造者」と呼ばれた。特にアポロンの彫刻は、自然主義と古代の神聖正面主義の痕跡を織り交ぜて表現され、力強さと優美さ、形態と理想が調和した荘厳な雰囲気を醸し出していた。例えば、カッセルのアポロ(紀元前 450年頃)がそうだ。しかし、彼はアナクレオン(紀元前 450年頃)のように、より人間的であまり理想化されていない、普通の人物像の作品も制作した。[22]

ポリュクレイトスの作品は、彼の人物像の基礎となった幾何学的プロポーションの規範の標準化、そして動きにおけるバランスの探求において特別な意義を持っていました。これは、彼の二つの主要著作『ドリフォロス』(紀元前440年)と『ディアドゥメネ』(紀元前430年)に見ることができますが、残念ながら、彼の作品はローマ時代の写本しか現存していません。ポリュクレイトスのもう一つの重要な貢献は、解剖学的研究(身体各部の可動関節、あるいは関節構造)、特に筋肉の研究です。彼の胴体の完成度の高さから、フランス語で「キュイラス・エステティック」(美的鎧)という愛称で呼ばれ、長きにわたり鎧のデザインに用いられてきました。[23]

プラクシテレスは、より多くの人物像(アポロ・サウロクトノス、紀元前360年、休息するサテュロス、紀元前365年、ヘルメスと幼子ディオニュソス、紀元前340年)をデザインしたが、それらは優雅な動きと潜在的な官能性を持ち、肉体的な力とある種の優雅さ、ほとんど甘美さを、流動的で繊細なデザインと組み合わせた。[24]

その後、ギリシャ彫刻は、ある意味で肉体と理想の融合を失い、より細身で筋肉質な人物像へと移行し、道徳的表現よりも行動が優勢になりました。これは、アンティキティラ島のエフェベ(紀元前340年)、エフェソスのストリギルを従える運動選手、マラトンのエフェベなどの作品に見ることができます。この時期に優れた芸術家の中には、ハリカルナッソスのマウソロス霊廟のフリーズの作者であるスコパスがいます。このフリーズには、ギリシャ人とアマゾネス(紀元前 350年頃)に代表される動きのある人物像が数多く描かれており、衣服の使用が特徴的で、特に体の他の部分は裸であるギリシャ人のマントによって、動きの感覚が表現されています。彼はまた、レオカレス廟の制作にも携わった。レオカレス廟は、新古典主義の最高傑作とされるベルヴェデーレのアポロ(紀元前330年頃~300年頃)の作者でも あり、このアポロは、デューラーの「アダム」(1504年)、ベルニーニの「アポロとダフネ」(1622年~1625年)、カノーヴァの「ペルセウスの凱旋」(1801年)、トーマス・クロフォードの「オルフェウス」(1838年)といった多くの現代芸術家に影響を与えた。この廟では、いわゆる「英雄的対角線」が取り入れられた。これは、足から手まで全身を貫く、はっきりとした対角線を描く姿勢で、後にエフェソスのアガシオによる「ボルゲーゼの剣闘士」(紀元前3世紀)や、カノーヴァの「ヘラクレスとテセウス」に至るクイリナーレ宮殿のディオスクーロス像など、精力的に再現されることになる。[25]

おそらくギリシア彫刻界最後の巨匠ともいえるリュシッポスは、小さな頭、よりほっそりとした体、そして長い脚という新しいプロポーションの規範を提唱した。これは彼の主力作品である『アポクシメノス』(紀元前325年)や『アギアス』 (紀元前337年)、『弓を引くエロス』(紀元前335年)、『休息するヘラクレス』(紀元前320年)に見られる。彼はまた、身体像に関しても、あまり理想主義的ではなく、より日常的で逸話的な要素を重視した新しい概念を提唱した。例えば、掻く運動選手の像や、ナポリの『休息するヘルメス』(紀元前330-320年)や、ベルリンの『アドラント』などである。リュシッポスはアレクサンドロス大王の肖像画家で、ルーブル美術館の『槍を持つアレクサンドロス』(紀元前330年)のように、裸の彫像を数多く制作した。 [26]

女性の裸体はあまり見られず、特に古代では、クーロイの裸体がコライの着衣姿と対照的だった。西洋美術が、特にルネッサンス以降、男性の裸体よりも女性の裸体の方が普通で楽しい主題と考えられたのと同様に、ギリシャでは、プラクシテレスのモデルとなった有名なフリュネの裁判に見られるように、特定の宗教的、道徳的側面から女性の裸体が禁じられていた。ギリシャの社会的には、女性は家事労働に従事させられ、男性の運動競技における裸体とは対照的に、女性は頭からつま先まで服を着用しなければならなかった。スパルタでのみ、女性は運動競技に参加し、太ももが見える短いチュニックを着用したが、これはギリシャの他の地域ではスキャンダラスな事実であった。女性の裸体の最初の痕跡は、紀元前6世紀の陶器に描かれた日常の場面に見られる。紀元前5世紀には、エスクイリーノのヴィーナス像のような最初の彫刻の痕跡が現れました。これはおそらくイシスの巫女を表わしたものでしょう。この像は、粗雑で精緻さに欠ける解剖学的構造を呈しており、がっしりとした体格で小柄ですが、七頭身像の規範に基づいた数学的なプロポーションを既に備えています。[27]

その後の裸婦像の発展は散発的で、全身裸婦像はほとんど見られず、部分的な裸婦像やドレープリー・ムイエ(「濡れた布」)と呼ばれる軽い衣服を体にまとった裸婦像が見られる。例えば、ルドヴィージの玉座のアフロディーテ、パエオニウスのニケ(紀元前425年)、ローマ・テルメ美術館所蔵のウェヌス・ジェネトリクスなどが挙げられる。紀元前400年頃、匿名の作者によってブロンズ製の少女像が制作された(ミュンヘン美術館所蔵)。これは古典的なコントラポストを体現しており、女性像に曲線(特に腰のアーチ部分)を与えている。この曲線はフランス語でデアンシュマン(「揺れる」)と呼ばれ、女性の体型を強調し、女性像表現のほぼ原型的なモデルとして残ることになる。[28]

女性の裸婦を扱った主要な古典彫刻家はプラクシテレスで、浴室に入る瞬間を描いた有名な「クニドスのアフロディーテ」(紀元前 350年頃)の作者である。この像は官能性と神秘性、肉体的快楽と精神的喚起が融合したものであり、ギリシア女性の美の理想を物質的に実現したものだ。彼はまた別の有名な像、衣服をまとった脚と裸の胸を持つ女神アフロディーテの像の作者でもあり、これはいくつかの模写が残っており、最も完全なものはルーブル美術館にあるいわゆる「アルルのビーナス」だが、紀元前100年頃の無名の芸術家による模写である「ミロのビーナス」が最も有名である。その後、女性の裸体画は進化し、カピトリノスのウェヌス(プラクシテレス自身の作とも言われる)に見られるように腕で裸体を隠している「恥じらいのウェヌス」や、ペプロスを持ち上げて腰と臀部を露わにしている「美しい臀部のウェヌス」といった類型が生まれた。後者のヘレニズム時代のオリジナルのローマ時代の複製が現存し、現在はナポリ国立考古学博物館に所蔵されている。[29]

女性の裸婦がもう少し多く描かれたジャンルは、バッカス祭やディオニュソス祭の表現です。サテュロスやシレーネに加え、官能的で奔放なポーズをとるメナドやネレイドの合唱団が登場し、その情景は葬儀用の石棺に広く描かれました。また、ドレスデンのメナドなど、ディオニュソス崇拝に関連する数々の像を制作したスコパスの彫刻工房でも頻繁に制作されたテーマです。特に、ネレイド像は大きな人気を博し、地中海全域で制作された後世の芸術に影響を与えました。解放された魂の象徴として、その表現は絵画や彫刻から宝飾品、カメオ、陶器の花瓶や杯、宝箱、石棺などに至るまで、様々な芸術技法において頻繁に装飾モチーフとして用いられました。ローマ帝国後期には広く普及し、アイルランドからアラビア、さらにはインドにまで広がり、空飛ぶガンダルヴァ像にその姿を見ることができます。中世においてさえ、その類型はイヴの性格と同一視されていました。[30]

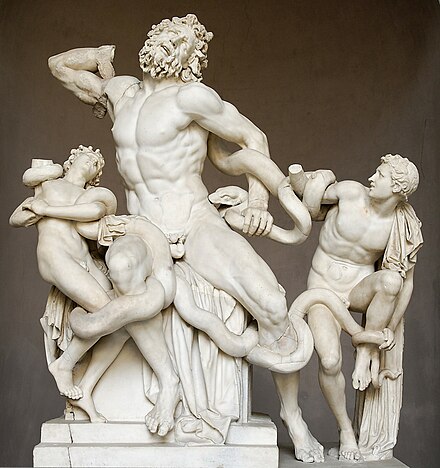

ヘレニズム時代、つまりアレクサンドロス大王の死後、ギリシャ文化が東地中海全域に広がった時代、人物像はより大きな躍動感と動きのねじれを獲得し、激化した感情と悲劇的な表情を呈し、古典期の静謐な均衡を破った。英雄や運動選手の生命力と勝利に満ちたエネルギーとは対照的に、敗北、ドラマ、苦悩、傷つき変形した、病んだ、あるいは切断された肉体の表現であるパトスが生まれた。英雄や運動選手が勝利者であったとすれば、今や人間は運命に屈し、神々の怒りに苦しみ、神は物質に、精神は肉体に勝利する。これは、ニオベの息子たちの虐殺、マルシュアスの苦悩、英雄(ヘクトールまたはメレアグロス)の死、ラオコーンの運命といった神話に見られ、当時の芸術で頻繁にテーマとなった。[31]

ヘレニズム彫刻の最初の制作中心地の 1 つはペルガモンで、ギリシャ全土から集まった彫刻家たちの工房が、明らかなリュシピウスの影響から始まり、カピトリーノ美術館の『瀕死のガリア人』(紀元前 230 年)やテルメ美術館の『ルドヴィージのガリア人』(紀元前 230 年)、ランツィのロッジアの『パトロクロスの体を支えるメネラウス』(紀元前 230 年 - 200 年、パスクイノ グループとも呼ばれる)、またはローマ音楽院の『マルシュアス』(紀元前 230年 - 200 年)に見られるように、人物像にドラマチックな表現を刻み込み、主に体のねじりを通して人物の苦痛を効果的に表現したスタイルを確立しました。彼の最高傑作は、アゲサンドロス、アテノドロス、ロドスのポリドロス(紀元前2世紀)による『ラオコーンとその息子たち』である。これはおそらく歴史上最もパトスを表現した作品であり、多彩な動き、絡み合う人物たち(父、息子、蛇)のねじれ、高ぶった感情、中央の人物の胴体と太ももの際立った筋肉、劇的な表情などが、潜在的な悲劇性を醸し出しており、見る者の心に恐怖と絶望、そして苦しむ人物たちへの哀れみを間違いなく呼び起こす。プリニウスによれば、ラオコーンは「あらゆる絵画と彫刻作品の中で最高の作品」である。[32]

ヘレニズム時代の作品としては、アポロニオスとトラレスのタウリスクスによるファルネーゼの雄牛像があり、これは初期の作品『ディルケーの受難』(紀元前130年)の模写である。これはダイナミックで表現力豊かな群像で、風景画の台座の上に、非常に写実的な動物たち、やや硬直した姿勢の若者たち、そして複雑な螺旋状のねじれで劇的な効果を生み出すディルケーの姿が描かれている。 [33]この時代のもう一つの有名な作品は、ビテュニアのドイダルサスによる『うずくまるヴィーナス』(紀元前3世紀)で、古代において高く評価され、宮殿、庭園、公共の建物の装飾として多数の模写が作られた。今日、世界中の美術館に複数の複製があり、また、ジャンボローニャ、アントワーヌ・コワズヴォ、ジャン=バティスト・カルポーなどの近代美術(主にルネサンス)や、マルカントニオ・ライモンディやマールテン・ファン・ヘームスケルクなどのデッサンや彫刻においても、複数の複製やバージョンが作られています。ルーベンスも、この像からインスピレーションを得て、いくつかの作品を制作しました。[34]同じくらい重要なのは、ポリュクレスの眠る両性具有者像(紀元前2世紀)で、オリジナルのブロンズは失われましたが、ローマ時代には複数の複製が作られ、その中で最も有名なのは、 17世紀初頭にディオクレティアヌス浴場で発見され、ベルニーニにより修復されたボルゲーゼの両性具有者像です。この作品には複数の複製があり、その一部は近代に制作されたもので、現在プラド美術館に所蔵されているスペイン国王フェリペ4世の依頼によるものは間違いなくベラスケスの『鏡の前のヴィーナス』に影響を与えた。[35]

-

うずくまるヴィーナス(紀元前 3 世紀)、ビテュニアのディオダルサス作、アルテンプ宮殿国立ローマ博物館。

-

眠っているサテュロスまたはバルベリーニ牧神(紀元前 200 年)、ミュンヘン グリプトテーク。

ローマ

.jpg/440px-Grupo_de_Orestes_y_Pílades_(Museo_del_Prado).jpg)

エトルリア美術に明確な先例があったことから、ローマ美術はギリシャ美術から多大な影響を受けました。ローマ帝国の拡大により、古典ギリシャ・ローマ美術はヨーロッパ、北アフリカ、近東のほぼ隅々にまで浸透し、これらの地域で発展する後の美術の発展基盤を築きました。ローマ人は建築と工学において非常に先進的でしたが、造形芸術においてはそれほど革新的ではありませんでした。ローマの彫像のほとんどはギリシャの作品の複製、あるいはギリシャからインスピレーションを得たものです。ヘレニズム世界の多くの芸術家がローマに移り住み、ギリシャ美術の精神を守り続けました。ローマの歴史家たちは古典ギリシャ時代以降に制作された美術作品を軽蔑し、ギリシャの黄金時代以降「芸術は停止した」とさえ主張しました。[36]

彫刻における最初の作品は、ローマに定住したギリシャの芸術家たちの作品であり、その中には、ベルヴェデーレのトルソ(紀元前50年)の作者であるアテネのアポロニオス、メディチのヴィーナス(紀元前1世紀)の作者であるクレオメネス、および茨の少年の作者であるパシテレスがいます。[37]パシテレスの弟子ステファノスは、アルバニの運動選手(紀元前50年)の作者であり、この像は大成功を収めました。18の複製が今日まで残っていることからその事実は裏付けられており、別の像とのバリエーションを生み出し、メルクリウスとウルカヌス、またはオレステスとピュラデスと同一視されるグループが作られました。そのグループの複製であるサン・イルデフォンソのグループ(紀元前10年)はプラド美術館に保存されており、2人の像はポリュクレイトスのドリフォロスとプラクシテレスのアポロ・サウロクトノスを彷彿とさせます。[38]ヘレニズム時代ギリシャ美術と様式的に関連する他の匿名の作品としては、ローマのテルメ美術館の『休息中のボクサー』 (紀元前100-50年)と、同じ美術館の『ヘレニズム時代の王子』(紀元前100-50年)がある。

ローマの作品自体については、ギリシャの影響を保ちながらも、神格化されたローマ皇帝の彫像は、ギリシャの神々のように裸体で特徴づけられており、ある種の観念論を保ちながらも、肖像の特徴においてはより自然を研究したものとなっている。[39]いくつかの作品では、ギリシャの彫像とは異なる様式上の特徴が認められ、例えば「キュレネのヴィーナス」(ローマ・テルメ美術館所蔵)では、ギリシャの人物像よりも解剖学的な自然主義が顕著である一方、ギリシャ女性の裸体の優雅さと官能性は保たれている。独自のテーマ的革新は「三美神」で、その複製がいくつか存在し(シエナ美術館、ルーブル美術館)、そのほとんどが1世紀のものとされている。これは、アフロディーテに随伴するカリテー(美の神々)の一団に由来する図像的主題であり、一般的には三姉妹(エウフロシネ、タリア、アグライア)が互いに腕を抱き合い、二人を正面向きに、中央の一人を後ろ向きに配して表現される。この主題はルネサンス期とバロック期に非常に成功を収めた。[40]

帝政期には、裸体への関心は低下し、彫刻の理想化が進むにつれて、写実主義や細部の描写、さらには醜悪で不快なものまでもが重要視されるようになった。こうしたスタイルは肖像画に最も顕著に現れた。それでもなお、ハドリアヌスの別荘を飾るマルスとメルクリウスの像(125)、アントニヌスの記念柱の土台に描かれたアントニヌスとファウスティナの神格化(161)、ローマのクイリナーレ広場にあるコンスタンティヌス浴場のモンテカヴァッロのディオスクーリ(330)など、素晴らしい作品が制作された。 [41]

絵画については、主にポンペイとヘルクラネウムの発掘調査によって多数のサンプルが入手されましたが、その装飾性が際立っているにもかかわらず、様式の多様性とテーマの豊かさに富み、神話から宴会、舞踏会、サーカスといった日常の場面まで、図像表現は多岐にわたります。これらの場面にはヌードが溢れており、エロティシズムへの明確な傾向が見られます。エロティシズムは、人生のもう一つの側面として、隠すことなく表現されています。ポンペイの壁を飾る裸婦画の中には、三美神、アフロディーテ・アナデュオメネー、プリアポスへの祈り、アイアスに誘拐されるカサンドラ、踊る牧神、サテュロスに驚かされるバッカンテ、ニンフのイフティマの強姦、アルカディアで息子テレポスを認識するヘラクレス、幼いアキレスに教えるケンタウロスのケイロン、アンドロメダを解放するペルセウス、アルドブランディーニの結婚式など、覚えておく価値のあるものがたくさんあります。 [42]

-

メノファントスのアフロディーテ(紀元前 1 世紀)、国立ローマ博物館。

-

カピトリーノのアンティノウス(2 世紀)、カピトリーノ美術館の剣闘士の間。

中世美術

西ローマ帝国の崩壊は、ヨーロッパにおける中世の幕開けを告げるものであった。帝国が小国に分裂し、新たな軍事貴族による社会的支配が強まったことで、それまで帝国官僚機構によって統治されていた領土はすべて封建化され、政治的・社会的に衰退の時代となった。古典芸術はゲルマン起源の新たな支配的文化によって再解釈され、新たな宗教であるキリスト教が中世の芸術作品のほとんどに浸透した。中世芸術は、旧キリスト教美術からプレロマネスク、ロマネスク、ゴシック、ビザンチン美術、ゲルマン美術まで、いくつかの段階を経た。[43]

中世の道徳神学では、裸体を4つの種類に分類していました。「自然裸体(nuditas naturalis)」は人間の自然な状態、「時間裸体(nuditas temporalis)」は移ろいによって強制された人工的な状態であり、一般的に貧困と結び付けられます。 「仮想裸体(nuditas virtualis)」は美徳と無垢の象徴、「犯罪裸体(nuditas criminalis)」は情欲と虚栄心と結び付けられます。中世美術、特に「ベアトゥスの黙示録」において、裸体表現のもう一つの頻繁な要素は死者の表現であり、これは地上のあらゆるものの剥奪の象徴として用いられました。[44]

キリスト教神学は人間を滅びゆく肉体と不滅の魂に分け、後者は唯一保存すべき貴重なものとみなした。異教の消滅とともに、裸体に関する図像的内容の大部分は失われ、聖書の中でそれを正当化するわずかな箇所に限られていた。裸体表現のごくわずかな例は、角張ったデフォルメされた人物像で、古典的な裸体の調和のとれたバランスからは程遠い。ただし、意図的に醜く傷ついた姿に描かれているのは、魂の単なる付属物とみなされていた肉体に対する軽蔑の表れである。女性の裸体表現(一般的にはイヴの姿)はごくわずかで、ふっくらとした腹、狭い肩、まっすぐな脚を持つ人物像である。顔は通常、個性的に描かれているが、これは古代には見られなかった。[45]

人物像は様式化の過程を経て、キリスト教の超越的性格と象徴言語を強調するために自然主義的な描写が失われ、遠近法の喪失と空間の幾何学化が進んだ。その結果、象徴的な内容、つまりイメージに内在するメッセージが現実の描写よりも重視されるような表現様式が生まれた。プラトンの身体を魂の牢獄とする思想に影響を受けたキリスト教は、自然主義的な解剖学的形態の研究への関心を失い、人間の表現においては表現力に重点を置くようになった。[46]

人体の比例に関する研究は中世に失われたが、人体は数学的および美的応用を伴う宇宙論的象徴の対象であった:ホモ・クアドラートゥス。プラトンの全集に始まる中世文化は、世界を偉大な動物、したがって人間とみなし、人間を世界、すなわち創造の大宇宙内の小宇宙として考えていた。この理論は、数字の4の象徴性を自然と関連づけ、それが芸術にも応用された:4つの基本方位、4つの季節、4つの月の満ち欠け、4つの主な風がある。そして、4は人間の数であり、この理論はウィトルウィウスと彼の人間の概念に遡り、伸ばした腕の幅が身長に相当する理想的な正方形であるとした。 [47]

キリスト教は、その初期にはユダヤ教の影響を強く受けており、裸体のみならず、ほぼあらゆる人体像を禁じていた。これは第二戒律に違反するからであり、異教の偶像は悪魔の住処であると非難していた。多くの異教の神々が絵画や彫刻の中で人間の姿で、しかも多くの場合裸で表現されていたため、原始キリスト教徒は裸体を異教の偶像崇拝と同一視し、直接悪魔との関連を見ていたわけではないにせよ、同一視していた。しかし、異教の終焉と新プラトン主義哲学がキリスト教道徳に吸収されると、肉体は魂の器として、裸体は人間の堕落した状態だが自然で容認できるものとして受け入れられるようになった。それでもなお、中世美術は古典美術に内在する肉体美の概念を完全に失い、アダムとイブなど聖書の描写を必要とする箇所において肉体美が表現された際も、それらは歪んだ身体で、基本的な線に還元され、性的特徴は最小限に抑えられ、美的特質を欠いた魅力のない身体であった。ゴシック時代は、より精巧でより自然主義的な前提に基づいた、人体像を作り直そうとする臆病な試みであったが、ある種の慣習主義の下では、形態は硬直化し、幾何学的な構造へと従属させられた。その結果、身体は常にキリスト教の図像学の前提の下で、イメージの象徴的側面に従属させられた。[48]

中世美術における裸体表現は少なく、楽園のアダムとイブやイエス・キリストの殉教と磔刑など、それを正当化する聖書の一節に限られていました。十字架上のイエス像には、主に二つの図像転写がありました。裸のキリスト像は「アンティオキアの」と呼ばれ、上着を着た救世主像は「エルサレムの」と呼ばれていました。しかし、初期キリスト教の清教徒的かつ反裸体主義的な性格にもかかわらず、裸体版が勝利を収め、特にカロリング朝時代以降、このテーマの正典版として受け入れられました。十字架上のキリストの受難は常に大きなドラマのテーマであり、ヘレニズム時代のパトスとも結びついています。裸体は激しい苦しみを表現する媒体であり、解剖学的構造が変形され、構造化されておらず、痛みという感情的な表現にさらされているように描かれています。イエスの典型的な姿勢は、頭を片側に傾け、体の位置を補正するために体を傾けた姿勢で、これは禿頭王カールの祈祷書とケルン大聖堂のゲロの十字架(10世紀)に初めて見られ、後にチマブーエの十字架の絵画のように、体がより湾曲し膝が曲がるなど、若干の修正が加えられました。しかし、北欧では、マティアス・グリューネヴァルトのイーゼンハイム祭壇画のように、苦痛が本物の発作のレベルに達する、より劇的な磔刑のイメージが定着しました。[49]

古代キリスト教美術は、数多くの古典的モチーフをキリスト教の情景へと変容させた。例えば、古代のヘルメス・モスコフォロスは善き羊飼いとしてのイエスの像となり、オルフェウスは慈悲深いキリストとなった。聖書においては、アダムとイブに加え、預言者ダニエルがライオンに囲まれた裸の姿で描かれることが多かった。この姿は、ローマのジョルダーノ墓地(4世紀)の壁画や、サン・ジョバンニ・イン・ラテラノ大聖堂の石棺にも保存されている。[50]

ロマネスク美術における裸婦像は少なく、一般に創世記のアダムとイブに関する箇所に限られているが、基本的な線で描かれており、女性の姿は男性の姿と乳房によってかろうじて区別がつき、乳房は形のない二つの突起物に縮小されていた。それらは粗雑で図式的な人物像であり、恥じらいの態度を示し、礼儀正しく局部を覆っているのが好まれた。これは、ヒルデスハイム大聖堂の青銅扉の天地創造、堕落、追放のレリーフ( 1010年頃)、モデナ大聖堂ファサードのアダムとイブ(ウィリゲルムス作、 1105年頃)、マデロの巨匠の楽園(プラド美術館)のアダムの創造、アダムとイブなどの例に見られる。[51]聖人の殉教場面では、全裸または部分的な裸体が見られる場合もあります。例えば、サン=サヴァン=シュル=ガルトンプ(ポワトゥー)の聖ギャバンと聖キプリアンの殉教場面などが挙げられます。同様の図像的テーマは、おそらくより自由に扱われたと思われる挿絵入りのミニアチュールにも見られます。例えば、ウェルギリウス写本(エル・エスコリアル修道院)のアダムとイブや、ヴィシェフラド福音書(1085年、プラハ大学)のキリストの洗礼などが挙げられます。[52]

ゴシック美術において裸体像は、主に13世紀初頭のゲルマン文化圏で制作され始めました。裸体を表現した最初の独立した等身大の像は、バンベルク大聖堂のアダムとイブ( 1235年頃)です。この像は、依然として硬直した聖職者的な形態の二本の柱のように見えますが、ある種の高貴な雰囲気を帯びています。[53]この時期、図像のレパートリーは若干拡大し、特にマタイによる福音書第24章と第25章に由来する「最後の審判」が取り入れられました。それまで、大聖堂のレリーフに描かれた聖書の物語の場面のほとんどは、黙示録で終わっていました。肉体の復活の場面では、肉体は裸である一方、魂は再生し、完全な美の基準に従って表現されるべきであると考察されたため、芸術家たちは古代ギリシャ・ローマ美術の作品に再び目を向け、ヴァンサン・ド・ボーヴェの『スペキュラム』などの論文を著した。そこには、古代の古典論文に基づいた芸術家への指示が記されていた。自然研究が再び始まり、一部の芸術家が公衆浴場に通ってより詳細に身体を研究していたことを示す資料がある。その証拠として、ブールジュ大聖堂の最後の審判には、古代の石棺の像を彷彿とさせる、より自然主義的な形態が見られた。この作品では、中央の女性はより女性的な形態をしており、コントラポストの姿勢にはポリレティア派の雰囲気が漂っている。ただし、彼女の形態は様式化されており、小さく離れた胸、平らな腹部、そして引き締まった腰など、官能的ではない。[54]

ゴシックヌードは少しずつ自然さと解剖学的な精密さを増していき、主題のレパートリーが広がり、裸体像の使用は彫刻やミニアチュールだけでなく、祭壇後壁の背面、ステンドグラス、聖歌隊席、金銀細工など、芸術のあらゆる分野に広まっていった。表現された新しい主題の中には、現世の財産を放棄することで物質的なすべてを剥ぎ取られた聖ヒエロニムスやその他の禁欲主義者、あるいはマグダラのマリアやエジプトのマリアといった女性像があった。時には楽園でイブを誘惑した蛇や聖ゲオルギオスに退治された竜も裸の人間の姿で表現される。[55]旧約聖書の特定の女性像、例えばバテシバ、スザンナ、ユディト、デリラ、サロメには、より官能的な表現が与えられた。時には、聖母マリアは幼子イエスに授乳しているため乳房を見せることも許された。例えばジャン・フーケの『聖母子』(1450年、『赤い天使の聖母』とも呼ばれる)がそうだ。[56]

14世紀初頭、オルヴィエート大聖堂のファサードはロレンツォ・マイターニの作品で、この絵画には裸婦像の大規模な連作が配置された。これは、創造、人間の堕落、最後の審判といった、この主題を正当化するあらゆるテーマを選んだことから、この画家の主題に対する個人的な関心を示しているように思われる。アダムの脇腹から立ち上がるイブの作品は、間違いなく古代のネレイデスの石棺に着想を得たもので、ある種の理想主義、魂の受け皿としての肉体の概念、それ自体が考察に値する概念を初めて示している。一方、最後の審判は北欧から着想を得たものと思われる。その多彩な場面は、戦いの石棺や古代のガリア人の死にゆく場面を彷彿とさせる。[57]

15世紀には、当時の流行、いわゆる「国際ゴシック」の流れを汲み、ヌードはより広く普及しました。この流行は、1400年頃にフランス、ブルゴーニュ、ネーデルラントの間で勃興しました。その初期の代表作の一つが、リンブール兄弟による『ベリー公爵の極楽浄土』(1416年)です。この作品には、 『堕落と楽園追放』の一場面が描かれており、エデンでの自然な生活から罪の恥辱へと堕ち、楽園から追放されたイヴが、イチジクの葉で覆われた恥辱のヴィーナスの姿へと変化していく様子が描かれています。彼女の細長く球根状の体、小さな胸、膨らんだ腹部は、200年間続くゴシック様式の女性ヌードの原型となりました。このことは、ヤン・ファン・エイクの『ヘントの祭壇画のイブ』、フーゴ・ファン・デル・グースの『アダムとイブ』 、ロヒール・ファン・デル・ウェイデンの『アダムとイブ』、ハンス・メムリンクの『虚栄心』 、コンラート・マイトの『ユディット』などの女性像にも見られ、裸体を恥ずべきものとした中世の慎み深い態度は、より官能的で、より挑発的で、より肉欲的な人間像へと移行しつつある。[58]スペインでは、バルトロメ・ベルメホの『キリストの冥界への降下』、フェルナンド・ガジェゴの『聖カタリナの殉教』 、ペレ・ヨアン(1429年)のタラゴナ大聖堂の主祭壇画の聖テクラ像、アイネ・ブルーの『聖ククファテの虐殺』(1504-1507年)など、官能とは程遠い、真剣なヌードへの最初の控えめな試みが現れました。[59]

多かれ少なかれ自然主義的な裸婦像は、ルネサンス以前のイタリアで、一般的には寓意の形で、ひっそりと現れ始めた。例えば、ピサ洗礼堂の説教壇に置かれたニコラ・ピサーノ作の『不屈の精神』のダニエル像は、ローマのヘラクレスに基づいており、多神教徒の運動選手をやや想起させる。また、ピサ大聖堂(1300-1310年)の説教壇に置かれたジョヴァンニ・ピサーノ作の『節制』像は、慎み深いヴィーナスの姿で、両腕で陰部を隠している。[60]これは、ジョットの作品、特にパドヴァのスクロヴェーニ礼拝堂の『最後の審判』にも見られる。[61]

-

アダムとイブと善悪の木、エミリアネンシス写本(994)のミニチュア、サン・ロレンソ・デ・エル・エスコリアル修道院王立図書館。

-

『宇宙と宇宙人による創造』、リベル・ディヴィノルム・オペラム(1230年)のミニチュア、ビンゲンのヒルデガルト作、スタダーレ・ディ・ルッカ図書館。

-

聖カタリナの殉教(15 世紀後半)、フェルナンド・ガジェゴサークル、マドリードのプラド美術館。

-

ハンス・メムリンク作「虚栄」(1485年)、ストラスブール美術館。

近世美術

近世美術(現代美術の同義語としてしばしば用いられる近代美術とは混同してはならない)は15世紀から18世紀にかけて発展した[注3] 。近世は政治的、経済的、社会的、そして文化的に急激な変化をもたらした。中央集権国家の統合は絶対主義の確立を意味し、新たな地理的発見、特にアメリカ大陸の発見は領土拡大と商業拡大の時代を開き、植民地主義の始まりを告げた。印刷機の発明は文化の普及を加速させ、あらゆる層の人々に開かれたものとなった。宗教は中世に持っていた優位性を失ったが、これはプロテスタントの台頭に助けられた。同時に、ヒューマニズムが新たな文化潮流として台頭し、人間と宇宙に対するより科学的な概念が台頭した[62] 。

ルネッサンス

15世紀(クアトロチェント)にイタリアで出現し、同世紀末から16世紀初頭にかけてヨーロッパ全土に広まりました。芸術家たちは古典ギリシャ・ローマ美術に触発されたため、中世の暗黒主義に倣い、芸術的な「ルネサンス」と呼ばれました。自然からインスピレーションを得た様式では、遠近法の使用など、新しい表現モデルが生まれました。宗教的なテーマを放棄することなく、人間とその周囲の描写がより重要になり、神話や歴史といった新しいテーマ、風景画や静物画といった新しいジャンルが登場し、ヌードの復活にも影響を与えました。美は中世のような象徴的なものではなく、調和とプロポーションに基づいた、より合理的で均整のとれた要素を持つようになりました。[64]

ルネサンス美術は、新たに幕を開けた近代の世界観の中心に人間を据えた人文主義哲学の人間中心主義と並行して、人体表現をより明確にするために解剖学の研究に依拠した。1543年、アンドレアス・ヴェサリウスの『人体について』(De humani corporis fabrica)が出版された。これは解剖に基づく人体解剖学の研究書であり、本書には本文に加え、ヤン・ファン・カルカル作とされる複数の人体図版が掲載されていた。これらの図版は、客観的リアリズムをますます重視する他の芸術家たちの絵画制作の基礎となった。本書の図版は芸術的な基準に基づいて構想され、骸骨や皮を剥がれた人物像が芸術的なポーズや、身振り手振りを交えた、ほとんど演劇的な態度で描かれていた。[65]

ルネサンス期の裸体画は、古代ギリシャ・ローマの古典絵画のモデルに影響を受けていますが、その役割は古代とは異なるものでした。ギリシャにおいて男性の裸体画が英雄像を体現していたのに対し、ルネサンス期のイタリアでは、裸体画はより美的な性格を持ち、宗教的戒律から脱却し、人間を再び宇宙の中心とする新たな世界観と結びついていました。女性の裸体画が際立ったのは、主に貴族や裕福な商人による庇護によってであり、彼らは社会における特権的な地位を示していました。こうして裸婦の世俗化が進み、中世の宗教的テーマから俗世俗的なものへと移り変わり、時には宗教的領域の外でこの種の表現を正当化しようとするやや強引な試みも見られました。ボッティチェリの主作である『プリマヴェーラ』と『ヴィーナスの誕生』は、マルシリオ・フィチーノがヴィーナス神話から推論した新プラトン主義の概念を表現しています。ヴィーナス神話は徳の高い女性の理想であり、誕生後、成人するまで裸であるにもかかわらず、彼女の最初の反応は古代の「恥じらいのヴィーナス」の概念に従って、身を覆うことです。[66]

ルネサンス美術は、肉体的にも精神的にも理想的な美の典型として、古典的な裸体像を復活させた。裸体は、最も自然主義的なものから最も象徴的なものまで、あらゆる構図の完璧な口実であり、後者は多様な寓意や擬人化を通して表現された。ルネサンスにおける人体表現は、時に裸体のための裸体、つまり芸術のための芸術であり、宗教的なものであれ神話的なものであれ、絵画の主題そのものをしばしば脱自然化させた。[67]ルネサンスにおいて、裸体はもはや恥の源ではなくなり、対照的に新たな英雄的、あるいは神聖な性格(sacra nuditas)を獲得した。[68]ルイ・レオ(『キリスト教美術の図像学』、1955年)によれば、「ルネサンスの芸術家たちは、勝利を収めた裸体像における人体の表現を、造形芸術の主たる対象とみなした」[68] 。

同様に、裸体は主要な芸術だけでなく、燭台からナイフやドアノブに至るまで、無数のマイナーな芸術や物品にも存在した。ベンヴェヌート・チェッリーニは「人体は最も完璧な形態である」という理由で、裸体表現の多さを正当化した。したがって、裸体が頻繁に描かれていることは驚くべきことではない。[69]一方、図像学においては、神話を題材とした作品が増え始めたにもかかわらず、芸術作品の大部分は依然として宗教的なものであった。そのため、古典的な裸体像の神話的人物像と、裸体で登場することが最も正当化されるキリスト教の人物像との間に、奇妙な共生関係が生まれた。このように、ギベルティの『イサクの犠牲』のイサクの姿が『ニオベの子ら』の古典的な類型を呈していること、ドナテッロの『墓』の横たわるキリストの姿が古典的なメレアグロスを思い起こさせていること、あるいはマサッチオの『楽園追放』のイヴの姿勢が恥辱のヴィーナスの姿勢であることなどが分かる。[70]

15世紀、ゴシック美術から受け継がれたいくつかの様式はイタリアで依然として生き残りましたが、徐々に自然主義と真実味を増していきました。これは、マザッチオ(『アダムとイブのエデン追放』、1425–1428年)、マソリーノ・ダ・パニカーレ( 『アダムとイブの誘惑』、1426–1427年)、アントネッロ・ダ・メッシーナ(『聖セバスティアヌス』、1476年、『天使に支えられた死せるキリスト』、1476–1479年)といった芸術家の作品に見て取れます。アンドレア・マンテーニャ( 『ゴルゴタの丘』1458年、『酒槽のあるバッカス祭』1470年、『死せるキリストを悼む』 1475 年頃- 1490年、『パルナッソス』 1497年、『ヴィーナス、マルス、ディアナ』制作年不明、『聖セバスティアヌス』 1459年、1480年、1490年の3つのバージョン)など。彫刻の分野でも同様のことが起こり、ロレンツォ・ギベルティはフィレンツェ洗礼堂の『天国の門』(1425-1452年)の作者で、『アダムとイブの創造』、『原罪』、『天国からの追放』などの作品を制作した。[71]

過去を打破し、古典的規範への回帰を象徴する最初の作品の一つが、ドナテッロの『ダビデ像』( 1440年頃)である。この作品は、当時としては極めて独創的で、その後50年間、比較対象となる作品がなかったほど、時代を先取りしていた。しかし、ドナテッロのモデルはギリシャの作品ほど運動能力に優れておらず、10代の少年のような優美で細身の体型を呈している。同様に、アポロ的な美の静謐さではなく、ディオニュソス的な美の官能性が感じられ、ユダヤ王の足元にあるゴリアテの頭部は、ギリシャ神話のワインの神像の台座を飾っていたサテュロスの頭部を想起させる。ドナテッロはまた、特に胴体において古典的なプロポーションから逸脱しており、ポリレティアンの美的胸甲とは対照的に、腰が体の中心軸を担っている。[72]

ドナテッロ以降、裸体像はよりダイナミックなものとなり、特にフィレンツェではアントニオ・ポライウォーロとボッティチェリ、ウンブリアではルカ・シニョレッリの作品において、動き、エネルギー、恍惚とした感情の表現が重視されるようになった。ポライウォーロは『メディチ宮殿のヘラクレスの二大功業』(1460年)において、ギリシャ彫刻の「英雄的対角線」を復活させ、裸体像の描写において卓越した技巧を披露した。ヴァザーリによれば、彼の裸体像の扱いは「彼以前のどの巨匠の作品よりも現代的」である。ポライウォーロは解剖学を深く研究し、ヴァザーリは彼が死体を解剖し、特に筋肉を研究したことを認めている。こうして彼は、形態の自然主義を基盤としながらも理想化されたギリシャ・ローマ古典主義から遠ざかり、ポライウォーロがもたらした解剖学的リアリズムからは程遠ざかりました。その好例が『ヘラクレスとアンタイオス』(1470年)に見られるように、英雄が巨人の体を押し潰す場面の緊張感は、作者の解剖学的な研究の細部を暗示しています。弟ピエロと共に『聖セバスティアヌスの殉教』(1475年)を制作しましたが、ここでも彼の解剖学的な研究が顕著に表れており、特に弓を引く力で顔を赤らめた射手が顕著です。[73]

ルカ・シニョレッリもまた、躍動感あふれる解剖学的な裸体画の代表的人物であり、特に、内包されたエネルギーを象徴する角張った、幅広く引き締まった肩と、肩と臀部、胸と腹部といったボリューム感の対照的な身体部位の単純化によって、人物像に緻密な可塑性と触感を与える表現が際立っています。オルヴィエート大聖堂(1499-1505)のフレスコ画では、《地獄に落とされる罪人たち》の人物像に見られるように、輪郭のはっきりした筋肉質な人物像に、潜在的な躍動感を宿しています。ポライウォーロとシニョレッリの緊張感と躍動感あふれる裸体画は、1480年から1505年まで続く「裸の男たちの戦い」の流行の火付け役となった。これは特別な図像的根拠もなく、ただ単にその美的感覚のためだった。フィレンツェではこれを「ベル・コルポ・イグンド(裸の男たちの闘い)」と呼んだ。それはベルトルド・ディ・ジョヴァンニの『戦い』(1480年)、ラファエロの『戦う男たち』、ミケランジェロの『ケンタウロスの戦い』(1492年)や『カッシーナの戦い』(1504年)といった作品に表れている。[74]

ボッティチェリは、中世道徳主義の時代を経て女性の裸体画の復興に大きく貢献したフィレンツェの新プラトン主義派と関連のある、高度に知的な裸体画を制作しました。この学派の主要理論家の一人、マルシリオ・フィチーノは、ヴィーナス像を美徳と神秘的な高揚の象徴として復活させ、プラトンの『饗宴』に登場する天上のヴィーナス(天上のヴィーナス)と世俗的なヴィーナス(自然のヴィーナス)を対比させ、女性における神性と地上性を象徴しました。この象徴主義は、ボッティチェリの二大作品『プリマヴェーラ』(1481年 - 1482年)と『ヴィーナスの誕生』(1484年)で見事に表現されています。このために、彼は手元にあった数少ない古典作品の遺物、すなわち石棺、宝飾品、レリーフ、陶磁器、素描からインスピレーションを得て、ルネッサンス以来の古典的美の理想として特定されることになる美の原型を創り出した。『プリマヴェーラ』では、ポンペイやヘルクラネウムの絵画、あるいはプリマ・ポルタやハドリアヌスの別荘のスタッコに由来する古典主義の感覚を備え、体の輪郭が見える半透明の繊細な布を使ったドレープリー・ムイエのジャンルを復活させた。しかし、ボッティチェリは古典的な裸婦像のボリューム感から離れ、現代の人体概念にもっと呼応する繊細で細い人物像を描き、その顔は理想的な古典的な原型よりも個人的で人間味にあふれている。ローマに滞在しシスティーナ礼拝堂のフレスコ画を制作した後に描かれた『ヴィーナスの誕生』では、教皇の街にあったローマの遺物に触れたことで、より純粋な古典主義が表れている。そのため、彼の描くヴィーナスはすでに衣服や道徳的な束縛を一切剥ぎ取られており、中世美術を完全に放棄して近代美術へと完全に移行している。図像の主題はアンジェロ・ポリツィアーノの『ジョストラ』[注 4]の詩句から取られているが、これはホメーロスの一節に触発されたもので、プリニウスによれば、その一節は既にアペレスが『アフロディーテ・アナデュオメネ』の中で描いていたという。彼は美しい貴族シモネッタ・ヴェスプッチをモデルにしている。ボッティチェリの人物像は、構図は古典主義的であるにもかかわらず、プロポーションというよりはリズムと構造においてゴシック様式の基準に合致している。曲線を描くため人物像は均等に分散されておらず、体重は右側に偏り、輪郭と髪の波打つような動きはまるで宙に浮いているかのような印象を与える。図像学的には、両腕で陰部を覆う恥じらいのヴィーナスが描かれている。この構図は、古典的な要素とはかけ離れた『アペレスの中傷』に登場する真実の姿にも部分的に繰り返されている。ボッティチェリの作品で裸婦が登場する作品には他に、『聖セバスティアヌス』(1474年)、『ナスタージョ・デッリ・オネスティの物語』(1482年 - 1483年)、『ヴィーナスとマルス』(1483年)、『聖ヒエロニムス、聖パウロ、聖ペテロとピエタ』(1490年 - 1492年) 、 『死せるキリストへの哀悼』(1492年 - 1495年)などがある。[75]

ピエロ・ディ・コジモは、シモネッタ・ヴェスプッチをクレオパトラ(1480年)として描いた作品も残しており、ファンタジーに恵まれた独創的な画家で、神話にインスピレーションを得た作品はやや風変わりな雰囲気を持ちながらも、豊かな感情と優しさにあふれ、人物は多様な動物とともに広大な風景の中に溶け込んでいる。その代表作には、『ウルカヌスとアイオロス』(1490年)、『ヴィーナス、マルス、キューピッド』(1490年)、『シレノスの災難』(1500年)、『プロクリスの死』(1500年)、『バッカスによる蜂蜜の発見』(1505年 - 1510年)、『ラピテース族とケンタウロス族の戦い』(1515年)、『プロメテウスの神話』(1515年)などがある。[76]

より穏やかな古典主義は、イタリア中部で感じられ、ピエロ・デッラ・フランチェスカの「アダムの死」(1452-1466)では裸婦像がペイディアスやポリュクレイトスの彫刻のような重厚さを帯びており、あるいはペルジーノの「アポロンとマルシュアス」(1495)には明らかにプラクシテレス的な雰囲気が漂っている。この古典主義はラファエロの「パルナッソス」(1511)で頂点を極めたが、これは間違いなく1479年に発見されたベルヴェデーレの「アポロン」にインスピレーションを得たもので、ラファエロはこのアポロンから、そのほっそりとした体つきだけでなく、聖人、詩人、哲学者に垣間見えるリズム、優美さ、調和も取り戻した。しかし、彼は古典的な人物像を単に再現したのではなく、自分のデザイン感覚に従って、芸術家の美的理想を甘美で調和のとれた概念として解釈した。[77]一方、ラファエロは、理想的な美の共観的なヴィジョンを提示する作品で、最も官能的な感覚から最も理想的な完璧さを引き出すことに成功した。『三美神』(1505年)では、ボッティチェリ風の優美なヴィーナスほど天空感はないものの、古代からの模倣というよりはむしろ芸術家特有の、やや素朴な古典主義でありながらも新鮮な活力に満ちた、簡素な形態を巧みに表現した。教皇室の部屋を描いた『アダムとイブ』(1508年)では、レオナルドの『レダ』に影響を受けた最初の女性の姿を、やや複雑なボリューム感で再現している。その後、アゴスティーノ・キージの遊園地ラ・ファルネジーナで制作した作品の中で、ネロの黄金宮殿の絵画にインスピレーションを得た「ガラテアの勝利」(1511年)が際立っています。ラファエロはこの作品の実現にあたり、どのモデルも十分に完璧だとは思えなかったため、異なるモデルから異なる部分を使用したことを認識していました。伝説によると、アペレスも同様にそう感じていたそうです。[78]

対照的に、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチは古典的な規範から逸脱し、広範な解剖学研究に基づいて自然主義的な人物像をデザインしました。初期にはポライウォーロの力強い造形に触発され、「アンギアーリの戦い」はミケランジェロの「カッシーナの戦い」の影響を受けています。後に、解剖学への深化により、彼の人物像は響き渡るほどのリアリズムを獲得しました。そこには科学的な関心が垣間見える一方で、ある種の英雄的な態度、道徳的かつ人間的な尊厳が表現され、静謐で生命力に満ちた力強さが与えられています。[79]しかし、解剖学への関心にもかかわらず、彼は数百、おそらくは数千ものデッサンにその関心をとらえており、今日では多くの美術館や個人コレクションに散在しているが、絵画においては裸婦を描いた作品はわずかしかなく、[80]例えばバッカス(または洗礼者聖ヨハネ、1510–1515年)やレダと白鳥などである。レダと白鳥は1504年から1506年の間に少なくとも3つのバージョンを制作しており、裸婦はもはや到達不可能な理想ではなく、創造的生命の象徴であることを証明している。[注 5]レオナルドにとって、解剖学の研究は、それ自体が目的というよりも、たとえ女性が服を着ていたとしても、表現される人物のプロポーションを知るために役立った。例えば、有名なモナ・リザの半裸のデッサン『ラ・ジョコンダ』(1503年)が現在シャンティイのコンデ美術館に所蔵されている。[81]

ルネサンス裸婦像の頂点はミケランジェロの作品で迎えられた。彼にとって裸婦は神聖な性格を帯びており、同時代の他の裸婦像とは比べものにならない尊厳をその肉体に与えていた。新プラトン主義の信念から、彼は男性美を前にした感情を極端に理想化した。そのため、彼の裸婦像の官能性は超越的なもの、すなわち高尚で非物質的、捉えがたい、崇高で純粋で無限なものの表現となった。彼の人物像は支配的で感動的、大いなる力と情熱、響き渡る生命力と強烈な精神力に満ちている。彼の宗教的作品でさえ、十字架に架けられたキリストの姿に本来備わっている苦しみの哀れみは失われ、バチカンのピエタ( 1498–1499)に見られるように、救い主を精神的な静けさで表すようになった。その静けさは、痛みよりも美しさへの同情を生むのである。[82]彼の初期の裸婦デッサンには、柔らかな古典的輪郭とはかけ離れた、神経質な表現の生き生きとした様子が表れており、プロポーションや幾何学的図式とはかけ離れた豊かな造形が特徴的である。解剖学は節くれだったが引き締まり、躍動的で、胴体の厚みが際立ち、筋肉が際立ち、輪郭がしっかりしており、ねじれや短縮された人物像の効果を強調している。その好例が、彼の初期の傑作の一つである「酔いどれバッカス」 (1496–1497年)である。フィレンツェの「ダビデ像」(1501–1504年)には、アポロ的な均衡のとれた古典主義の雰囲気が残っているが、個人的な解釈がなされており、胴体はギリシャ彫像のように見えるものの、頭と手足の不均衡が緊張を表し、反抗的な表情は古典的な精神から逸脱している。ルーブル美術館所蔵の奴隷像(瀕死の奴隷と反抗的な奴隷、1513年)の劇的な表現も同様で、ヘレニズム美術のヌーバイド像を想起させ、ラオコーンの影響を示している(ミケランジェロは1506年にサン・ピエトロ・イン・ヴィンコリ近郊で発掘されたこの彫刻群を最初に目にした人物の一人である)。同様に、メディチ家の墓(1524年)の像もギリシャ美術を彷彿とさせる。男性像(昼と薄暮)はベルヴェデーレのトルソを、女性像(夜明けと夜)はバチカンのアリアドネを彷彿とさせる。[83]

その後、豊満で躍動感がありながらも感情の激しさに満ちた解剖学という彼の構想は、システィーナ礼拝堂のアダム(1508-1512年)に体現された。パルテノン神殿のペディメントに描かれたディオニュソス像を彷彿とさせるが、調和のとれたフィディアス像とはかけ離れた、生命力に満ちた力強さを帯びている。同様に、システィーナ天井画の運動選手像(通常は単にイグヌーディ(裸体)と呼ばれる)は、運動能力のエネルギーと、聖書の預言者たちの魂を体現する神聖な使命の超越性とが調和し、物質界と精神界の仲介役を調和的に果たしている。そのため、その肉体的な美しさは神の完全性を反映している。「大洪水」(1509年)などの他の場面でも、彼は肉体的な力強さが精神的な強さを物語る、力強い人物像を描いている。「イヴの創造」(1509–1510年)は、輪郭が非常にはっきりした、丸々とした力強い女性像を描いている。一方、「最後の審判のキリスト」(1536–1541年)は、正統神( sol justitiae)として理解されるアポロンの荘厳さを備えているが、その丸み――ほぼ四角い胴体に顕著――は、古典期の規範から既に大きく逸脱している。彼が描くイエス像は、もはやビザンチン様式の典型的な髭面の人物像ではなく、オリンポスの神、あるいはヘレニズム時代の王の肖像であり、ユダヤ人の大工というよりはアレクサンダー大王に近い。神秘主義的なキリスト教の禁欲主義者に期待されるよりも、より運動的な体格をしている。[84]最後の作品である3つのピエタ(パレストリーナ、ドゥオーモ、ロンダニーニのピエタ)では、彼は物理的な美の理想を完全に放棄し、歪んだ人物像(パレストリーナ)、角張った人物像(ドゥオーモ)、あるいはゴシック様式に近い図式(ロンダニーニ)を描いている。[85]

ギリシャ彫刻の黄金時代以来、裸体と偉大な具象芸術の同一性を初めて完全に理解したのはミケランジェロでした。彼以前は、裸体は衣服に包まれた人物像を捉える手段として、科学的な視点から研究されていました。ミケランジェロは裸体自体が目的であると理解し、裸体を自身の芸術の至高の目的としました。彼にとって、芸術と裸体は同義語でした。

— バーナード・ベレンソン『イタリア・ルネサンスの画家たち』(1954年)[86]

16世紀には、マルカントニオ・ライモンディの作品をはじめとする古典ギリシャ・ローマ作品を題材とした版画が出版され、裸婦像は広く普及しました。ヴェネツィア派が台頭し、古典主義的な手法の継承のみならず、新たな技法や様式の革新と実験においても、裸婦像に重要な貢献を果たしました。ヴェネツィア人は、室内でも自然風景の中でも、より精巧な構図の中に裸婦像を調和させることに成功しました。また、色彩と照明の革新によって、裸婦像にさらなるリアリズムと官能性を与え、古典の規範から逸脱し始めた、大きくて生き生きとした人物像を生み出しました。この様式の主な創始者はジョルジョーネであるが、ジョルジョーネは女性の裸体を一般的な装飾スキームの中に組み込んだ最初の人物であり、フォンダコ・デイ・テデスキ(1507-1508年、現在は消失)のフレスコ画や、田園音楽会(1510年) 、あるいは横たわる姿勢がうんざりするほど模倣されている「眠れるヴィーナス」(1507-1510年)に見られるように。ジョルジョーネの裸体画の豊かなプロポーションと広いウエストという身体的類型は、長らくヴェネツィアの女性裸体画を支配し、デューラーを介してドイツやネーデルラントに伝わり、バロック時代のルーベンスなどの芸術家の作品に生き残ったことは注目に値する。[87]

.jpg/440px-Tiziano_-_Amor_Sacro_y_Amor_Profano_(Galería_Borghese,_Roma,_1514).jpg)

ジョルジョーネの初期からの模倣者としてティツィアーノが挙げられます。彼の『ウルビーノのヴィーナス』(1538年)と『パルドのヴィーナス』(あるいは『ユピテルとアンティオペ』 (1534年 - 1540年))は『眠れるヴィーナス』と同じポーズを再現しているものの、より大きな名声を得ています。『聖なる愛と世俗の愛』 (1514年 - 1515年)では、プラトンの『饗宴』に描かれた天上のヴィーナスと、フィチーノやフィレンツェの新プラトン学派によって復活した世俗のヴィーナスの神話を捉えています。天上のヴィーナスは、道徳的美徳の純粋さを鑑みて、古典的な裸婦像の理想に従って裸体であり、一方、世俗のヴィーナスは、不道徳さの恥辱から、衣服をまとった姿で描かれています。他の作品でも、彼は豊満で肉感的な女性の原型を作り続け、バッカスとアリアドネ(1520–1523)や懺悔するマグダラのマリア(1531–1533)や、ヴィーナスと音楽家(1547)や、オルガン奏者、キューピッド、犬とヴィーナス(1550)や、黄金の雨を受けるダナエ(1553)や、ヴィーナスとアドニス(1553)や、エウロペの略奪(1559–1562)や、ディアナとアクタイオン(1559)や、ディアナとカリスト(1559)、アルフォンソ1世デステ(1518–1526)のために描いた2つのバッカス祭の絵、あるいはエルズミーア・コレクションのヴィーナス・アナディオメネ(1520)などがある。そのあからさまな官能性は、裸婦を主題とするようになった出発点であり、これは印象派にも引き継がれることになる。[89]

ティツィアーノの弟子にはパリス・ボルドーネ(『眠れるヴィーナスとキューピッド』 1540年、『水浴するバテシバ』1549年、『ヴィーナスとマルスとキューピッド』1560年)とティントレットがいた。ティントレットの野望はミケランジェロのデッサンとティツィアーノの色彩を再び融合させることだったが、完全には達成されなかった。ティントレットの作品は大型で、多数の人物像と、彼が愛したヴェネツィアの明るい性質を反映したまばゆい光が描かれている。ヴェネツィアのドゥカーレ宮殿(1560年 - 1578年)の装飾では、古典神話(マルス、ミネルヴァ、メルクリウス、バッカス、アリアドネ、ウルカヌス、三美神)からの多数の人物像を、通常は短縮法をふんだんに用いたポーズや遠近法で描き、真に神格化された裸婦像を制作した。その他の裸婦画には、『ヨセフとポティファルの妻』(1544年)、『アダムとイブ』(1550年 - 1552年)、『ヴィーナス、ウルカヌス、マルス』 (1555年)、『アルシノエの解放』 (1555年 - 1556年)、『スザンナと長老たち』 (1560年 - 1565年)、 『天の川の起源』(1575年 - 1582年)、『ユディトとホロフェルネス』(1579年)などがある。娘のマリエッタ・ロブスティも父の跡を継ぎ、幾度となく父のモデルを務めた。[90]

パオロ・ヴェロネーゼは、無限の色合いを巧みに組み合わせた色彩と構図を完璧に掌握し、豪華絢爛で遊び心のある装飾的な場面を再現することに力を注ぎ、ドージェのヴェネツィアの華やかさを強調しました。彼の宗教画でさえ、祝祭的で喜びに満ち、世俗的で、時にやや不遜な性格を帯びています。しかし、彼の裸婦画は慎ましく、控えめで、露骨な描写はなく、チュニックや衣服の襞の間の裸体部分のみを描いています。例えば、『愛の寓意I 不貞』(1575–1580年)、『イヴの創造』(1575–1580年)、『マルスとヴィーナス』(1580年)、『スザンナと長老たち』 (1580年) 、 『ヴィーナスとアドニス』(1580年)などが挙げられます。[91]

一方、コレッジョは古典主義から完全に離れ、形態や人物だけでなく、色彩の遊びや光の効果においても、レオナルドのスフマートの影響を受けた、芸術家の溢れんばかりの想像力のみに委ねられた独創的な構成を精緻に描き出した。『サテュロスとヴィーナスとキューピッド』 (または『ユピテルとアンティオペ』 、1524–1525年)、『キューピッドの教育』(1528年)、『ダナエ』(1530年)、『レダと白鳥』(1531–1532年) 、 『ユピテルとイオ』(1531–1532年)といった作品では、人物像を気まぐれで躍動的なポーズで描き、暗い絵画の他の部分から際立たせることで、芸術家の主な関心事に焦点を絞っている。[92]

16世紀後半にはマニエリスム[注 6]が出現し、近代美術はこれをもって特定の様式へと転換した。すなわち、事物はあるがままに表現されるのではなく、芸術家が見たように表現されるのである。美は相対化され、科学に基づくルネサンス期の単一美から、自然から派生したマニエリスム期の多元的な美へと移り変わる。マニエリスムにとって、古典美は空虚で魂を欠いたものであり、精神的で夢想的で主観的で無秩序な美と対置される。これはペトラルカの「ノン・ソー・シェ(私は何なのかわからない)」[93]という定式に要約される。マニエリスムの裸婦像は、細長く誇張された、ほっそりとしたフォルムで、ほとんどマナー的な優雅さを帯びている。それは、一方ではミケランジェロの形式的な歪み、他方ではパルミジャニーノの優雅さを併せ持つ。良い例としては、ブロンズィーノの「ヴィーナスとキューピッドの寓意」(または情熱の寓意、1540-1545年)が挙げられますが、非常に細身で、ほとんど好色な態度をとっているヴィーナスのジグザグの姿勢は、ミケランジェロの「ピエタ」の死せるキリストに由来しています。これらの洗練された優美さを持つ細身の像は、彫刻、特にブロンズ作品にも多く見られ、バッチョ バンディネッリ(ヘラクレスとカークス、1534年、フィレンツェのシニョリーア広場にあるミケランジェロのダビデ像の隣に所蔵)、バルトロメオ アンマナーティ(レダと白鳥、1535年、ヴィーナス、1558年、ネプチューンの噴水、1563–1565年)、ベンヴェヌート チェッリーニ(エル エスコリアルの磔刑像、1539年、フランチェスコ 1 世の塩入れ、1540–1543年、ガニメデ、1547年、メデューサの首を持つペルセウス、1554年)、ジャンボローニャ(ペリシテ人を殺すサムソン、1562年、メルクリウス、1564年、ネプチューンの噴水、 1565年の『フィレンツェの凱旋』 、 1570年の『ピサの凱旋』、1582年の『サビニの女たちの略奪』 、1599年の『ヘラクレスとケンタウロスのネッソス』などである。[94]一方、裸婦の悲劇的側面、つまりヘレニズム的情念は、ポントルモとロッソ・フィオレンティーノによって、概して宗教的な主題を用いて開拓され、マニエリスムの感情主義をよりよく表現することができた。例えばロッソの『イエトロの娘たちを守るモーゼ』(1523年)では、その平坦で角張った身体は古典主義とは正反対である。[95]

16世紀、裸体画が芸術的テーマとして受け入れられ、それがイタリアからヨーロッパ各地へと広がり、特にドイツとオランダにおいて、この種の作品を熱心に消費するブルジョワ階級の間で、裸体画への大きな需要が生まれました。裸体画は非常に人気が高く、エラスムス・フォン・ロッテルダムの『新約聖書』の表紙にも登場しました。この分野で最も人気のある芸術家の一人はルーカス・クラナッハ(父)で、彼は作品を通してゴシック起源の北欧裸婦像のより個人的なバージョンを作り上げました。その丸みを帯びたフォルムを保ちながらも、より様式化され、古典的な規範に従い、長くほっそりとした脚、細い腰、緩やかに波打つシルエットで表現されています。その例としては、 『ヴィーナスとキューピッド』 (1509年)、『泉のニンフ』(1518年)、『ルクレティア』(1525年)、『パリスの審判』(1527年)、『アダムとイブ』(1528年)、『アポロとダイアナ』(1530年)、 『三美神』 (1530年)、『黄金時代』(1530年)、『ヴィーナス』(1532年) 、 『蜂蜜を盗むヴィーナスとキューピッド』(1534年) 、 『正義の寓意』 (1537年)、 『若返りの泉』 (1546年)、『ダイアナとアクタイオン』(1550年 - 1553年)などがあります。彼の人物像は帽子、ベルト、ベール、ネックレスといった複数の小道具を用いてモデルのエロティシズムを強調し、後に繰り返されるイメージを確立した。[96]

アルブレヒト・デューラーは、祖国に深く根付いたゴシック美術の様式を受け継ぎながらも、イタリア・ルネサンス古典主義の研究によって進化を遂げました。初期の作品には、小さな胸とふくらんだ腹部を持つ、細長い体型のゴシック女性の原型が見られるものがあり、例えば『主婦』(1493年)、『女の浴場』(1496年) 、 『四人の魔女』(1497年)などが挙げられます。その後、彼は人体のプロポーションの研究に没頭し、解剖学的な完璧さへの鍵を探ろうとしましたが、成果は芳しくありませんでした。しかし、こうして彼はある種の古典主義的様式へと近づいていきました。それは1504年の『アダムとイブ』に見られるように、古典的調和とは幾何学的な規則の規範というよりもむしろ精神状態であったことを示しています。それでも彼は満足せず、晩年の作品では『ルクレティアの自殺』(1518年)のように、ゴシック美術の球根状の形態へと回帰しました。画家であると同時に優れた版画家でもあったデューラーの最高傑作には、ベレニス、博士の夢、海の怪物といった裸婦像、あるいは寓意画や皇帝の凱旋シリーズ、あるいはイエスの受難と死、聖ヒエロニムス、聖ジュヌヴィエーヴ、聖マグダラのマリアといった聖人の生涯を描いた版画などがある。デューラーの作品は、ウルス・グラーフ( 『猛り狂う軍隊』、1520年)やニクラウス・マヌエル・ドイチュ(『パリスの審判』、1516-1528年)の作品に見られるように、ゴシック様式と古典的理想が融合した作品において、ゲルマン世界の多くの芸術家に影響を与えた。[97]

ハンス・バルドゥングもまたデューラーの弟子で、人生のはかなさを想起させる、死や年齢を擬人化した、道徳的な含みを持つ寓意的な作品を数多く手がけた。例えば、『聖セバスチャン三連 祭壇画』(1507年)、『二人の恋人と死』(1509年 - 1511年)、 『女と死の三歳』 ( 1510年)、『イヴと蛇と死』(1512年) 、『三人の魔女』 (1514年)、 『死と女』(1518年 - 1520年)、『虚栄』(1529年)、『ヘラクレスとアンタイオス』(1530年)、『アダムとイヴ』 (1535年)、 『女の七歳』(1544年)などである。一方、ハンス・ホルバインは宗教画や肖像画を多く手がけ、裸婦像は少なかったが、中でも傑作『墓の中の死せるキリストの遺体』 (1521年)は特筆すべき作品である。[98]

ネーデルラントでは、ヒエロニムス・ボスがゴシック様式の連続性をある程度表現したが、より自然主義的で、溢れんばかりのファンタジーで描かれており、彼の作品は創造性と想像力の驚異と言えるだろう。『快楽の園』(1480年 - 1490年)、『最後の審判』(1482年)、『七つの大罪と四つの最後のもの』(1485年) 、『干し草の山三連祭壇画』(1500年 - 1502年)では、裸の人間あるいは人間以下の姿(悪魔、サテュロス、神話上の動物、怪物、空想上の生き物)が、いかなる図像学的意味も超越し、芸術家の熱狂的な想像力のみに従う情欲の激発の中で増殖している。ピーテル・ブリューゲル(父)もまた、広大なパノラマと多数の人物像を描いた作品を制作し、風景画や風俗肖像画を好んだが、裸婦画は少ない。これらは、彼の息子ヤン・ブリューゲル・ド・ヴェルールの作品に顕著に表れています。彼は、神話や聖書の場面を題材に、小さな裸体人物を多数描いた風景画を制作しました。ヤン・ホッサールトはフランドルでラファエル派の影響を受け、故郷に神話寓話を導入しました。その例としては、『ネプトゥヌスとアンフィトリテ』(1516年)、『両性具有とサルマキスの変身』(1520年)、『ダナエ』(1527年)などが挙げられます。[99]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Gabrielle_d'Estrées_and_one_of_her_sisters_(30612730014)_(cropped).jpg)

フランスでは、ゴシックからマニエリスムへと芸術が急速に発展し、初期ルネサンスの古典主義の影響はほとんど感じられませんでした。これは主に、ロッソ・フィオレンティーノ、フランチェスコ・プリマティッチオ、ベンヴェヌート・チェッリーニといったイタリアのマニエリスム芸術家たちがフォンテーヌブロー宮殿の作品に滞在したためです。彼らはフォンテーヌブロー派を生み出し、宮廷的で官能的な趣味、装飾的で官能的で物憂げな優雅さを特徴とし、壁画やスタッコのレリーフが主流でした。プリマティッチオの優雅で角張った、長い手足と小さな頭を持つ人物像は流行し、16世紀末までフランス芸術に残りました。この流派の作品には無名の作者によるものもあり、例えば「狩猟の女神ディアナ」( 1550年頃)や「ガブリエル・デストレと妹のヴィラール公爵夫人の肖像」(1594年)は、宮廷の優雅なエロティシズムを描いている。著名な作者としては、ジャン・クザン・ザ・エルダーの「イヴ・プリマ・パンドラ」(1550年)、フランソワ・クルーエの「ディアナの入浴」(1550年)、トゥーサン・デュブレイユの「貴婦人の目覚め」、彫刻ではジャン・グージョンの「狩猟の女神ディアナ」(1550年)とジェルマン・ピロンの「三美神」(1560年)がいる。裸婦像は、タペストリーから陶芸、金細工に至るまで、あらゆるマイナーアートにもこの同じ環境で表現されており、例えばピエール・レモンの「アダムとイブの物語」を6つの段落で描いた有名なエナメル細工の皿などがある。 [100]

スペインではルネサンスの影響が遅れて到来し、ゴシック様式は16世紀半ば近くまで存続しました。それ以外の点では、革新はテーマよりも様式的なものであり、中世と同様に宗教的なテーマが主流でした。エル・グレコは当時のスペイン絵画の主要な革新者の一人でした。ヴェネツィア派で学んだ彼は、この流派から作品の鮮やかな色彩を得ていますが、長身で不均衡な人物像はイタリア古典主義の自然主義というよりも、ある種の形式的表現主義を示しています。彼の作品の多くは宗教的なものです。しかし、そこには多かれ少なかれテーマにふさわしい裸婦像が描かれており、全作品で100点以上の裸婦像を数えることができます。この傾向は、聖セバスティアヌスの殉教(1577–1578)、洗礼者聖ヨハネ(1577–1579)、聖三位一体(1577–1580)、聖モーリスの殉教(1580–1582)、二人の寄進者によって礼拝される十字架上のキリスト(1590)、キリストの洗礼(1596–1600)、磔刑(1597–1600)、聖マルティヌスと乞食(1597–1600)、神殿から両替商を追い払うキリスト(1609)、聖ヨハネの幻視(1609–1614) 、ラオコーンとその息子たち(1614)などの作品に見ることができます。また、彫刻家としても、プラド美術館所蔵のエピメテウスとパンドラ(1600–1610)などの作品を残しています。両登場人物の性器が隠すことなくリアルに描かれていることは注目に値する。[101]

スペイン・ルネサンス期の他の芸術作品では、礼儀作法と慎み深さが主流であり、ビセンテ・カルドゥーチョの『絵画の寓意』、フランシスコ・パチェコの『絵画芸術』 、フセペ・マルティネスの『実践的演説』といった論文の中で芸術理論にまで高められたスペイン美術の黄金律である。こうした文脈において、裸体の人物像は宗教的領域、特にアロンソ・ベルルゲテの『聖セバスティアヌス』(1526年 - 1532年)、フアン・デ・ジュニの『キリストの埋葬』(1541年 - 1545年)、フアン・マルティネス・モンタニェスの『悔悛の聖ヒエロニムス』(1598年)といった彫刻作品にのみ見られる。この規則の例外はごくわずかで、例えばガスパール・ベセラによるミケランジェレスクの影響を受けたエル・パルド王宮のダナエ物語のフレスコ画(1563年)などがある。[102]

-

ハンス・バルドゥング作「女性と死の三つの時代」(1510年)、ウィーン美術史美術館。

-

若返りの泉(1546年)、ルーカス・クラナッハ(父)作、ベルリン・ゲオルゲ美術館。

バロック

バロック[注7]は17世紀から18世紀初頭にかけて発展した。政治と宗教の両面で大きな論争が繰り広げられた時代であり、絶対主義国家を強固にするカトリック反改革派諸国と、より議会主義的な性格を持つプロテスタント諸国との間に分裂が生じた。芸術はより洗練され、華麗になった。ある種の古典主義的合理主義は生き残ったものの、よりダイナミックで劇的な形態、意外性や逸話性、錯覚や効果音への嗜好が高まった。 [ 103]

バロック時代においても、女性の裸体は貴族のパトロンにとって、依然として享楽の対象として優勢であり、彼らは女性が一般的に男性に従属するこの種の構図を好んでいました。神話的なテーマに加え、裸の女性が正義、真実、寛大さなどの概念を表す寓意的な肖像画を描く習慣も始まりました。[104]バロックの裸体画は、マニエリスムやミケランジェロの作品に見られるねじれとダイナミズムの効果を強調しました。彼らはミケランジェロから螺旋構図を取り入れました。ミケランジェロはフィレンツェのヴェッキオ宮殿の勝利の寓意像に螺旋構図を導入し、これにより胴体の重量を支えるためのより強固な基盤を得ることができました。こうして、古典的な「英雄的対角線」は「英雄的螺旋」へと発展し、激しく力強い動きによってバロック芸術のドラマ性と効果性を説得力のある形で表現することができました。[105]

バロック時代は、裸婦画家のピーテル・パウル・ルーベンスが先駆けであり、そのたくましく肉感的な女性像は、当時の美の概念に新たな一時代を築きました。しかし、この肉欲的な豊かさにもかかわらず、宗教的なテーマの作品も数多く残したルーベンスの作品には、ある種の理想主義、ある種の自然の純粋さが欠けてはいません。それが彼のキャンバスに、夢見るような率直さ、人間と自然との関係についての楽観的で統合的なビジョンを与えています。ルーベンスは人物の図柄を非常に重視し、そのために先人の芸術家の作品を徹底的に研究し、とりわけ裸婦画に関しては、ミケランジェロ、ティツィアーノ、マルカントニオ・ライモンディといった最高の資料を得ました。彼は、肌の色調の正確な色調表現において、ティツィアーノとルノワールに匹敵する名手でした。肌の質感の多様性、そして明るさや光の反射による多様な効果を巧みに捉えることにも長けていました。また、身体の動きや人物像に重みと立体感を与えることにも気を配っていました。しかし、心理的な側面や表情への配慮も怠りませんでした。彼の描く人物像の顔には、気ままな幸福感、自分が美しいと自覚しながらもうぬぼれのない誇り、そして生命の恵みに対する画家自身の生々しい感謝の念が見て取れます。[106]ヌードに関連した作品の中で特筆すべきものは、以下の通りである:『セネカの死』(1611–1615)、『ヴィーナス、キューピッド、バッカス、ケレス』( 1612–1613)、『キューピッドとプシュケ』(1612–1615 )、『ヴィーナスの頭飾り』(1615 )、 『ライオンの穴のダニエル』 (1615)、『ペルセウスとアンドロメダ』(1622)、『マリー・ド・メディシスのマルセイユ到着』(1622–1625)、『真実の勝利』(1622–1625)、『マルスから平和を守るミネルヴァ』(1629)、『ヴィーナスとアドニス』(1635)、『三美神』(1636–1639、彼の生涯の二人の女性、イザベラ・ブラントとエレーヌ・フールマンが描かれている)、『レウキッポスの娘たちの略奪』(1636年)、『天の川誕生』(1636–1638年)、『ディアナとカリスト』(1637–1638年)、『牧神に驚くディアナとニンフたち』(1639–1640年)、『パリスの審判』(1639年)など。2000点以上の絵画を制作した彼は、おそらく歴史上最も多くの裸婦を描いた画家であろう。[107]

宗教的なテーマに関しては、ルーベンスは他の裸婦画と同様の総合力を発揮し、人物に肉体的な実体を与えて精神的な側面を高めた。アントワープ大聖堂の2つの作品『十字架上』(1611年)と『十字架降下』(1613年)に見られるように、これらの作品にもミケランジェレスクの影響とラオコーン像の波打つような動きの同化が見られる。これらの像では肉体の色が重要な役割を果たしており、キリストの青白く青白い姿と他の人物の鮮やかな色の対比が、場面のドラマ性により大きな効果を与えている。ボイマンス・ファン・ベーニンゲン美術館の「磔刑」(1620年)にも同様の効果が見られる。キリストと盗賊の異なる色彩が嵐のような光の効果に加えられ、異なる人物の解剖学的構造の差異が盗賊の粗野な物質性とは対照的にイエスの理想的な体格を強調している。[108]

ルーベンスの弟子には、アンソニー・ヴァン・ダイクとヤコブ・ヨルダーンスがいます。ヴァン・ダイクは偉大な肖像画家でしたが、プラド美術館の『ピエタ』 (1618年 - 1620年)やミュンヘンのアルテ・ピナコテークにある『聖セバスティアヌス』 、あるいは『サテュロスに驚かされるダイアナとエンディミオン』 (1622年 - 1627年)や『ビーナスとアドニスに扮したバッキンガム公爵夫妻』 (1620年)に見られるように、イタリアの影響を強く受け、より個人的なスタイルへと進化していきました。ヨルダーンスは、アントワープの天才の裸婦画に匹敵するほどの裸婦画を数多く制作したことからもわかるように、その頂点には達しなかったものの、師匠に忠実であった。その証拠として、ヨルダーンスは『サテュロスと農夫』(制作年不明)、『エウロペの略奪』(1615–1616)、 『豊穣』( 1623)、『パンとシュリンクス』( 1625)、『アポロンとマルシュアス』 (1625)、 『縛られたプロメテウス』(1640)、『エリクトニオスを見つけるケクロプスの娘たち』 (1640)、 『バッカスの勝利』(1645)、『ディアナの休息』(1645–1655)、『大地の豊穣』(1649)などを挙げている。[109]

ルーベンスの理想主義とは対極にあるのがレンブラントの作品で、ゴシック様式を起源とする北欧裸婦像の丸みを帯びたフォルムを受け継いでおり、人物描写はルーベンスの作品と同様に生々しく、しかしより平凡で、肉のひだや皮膚のしわを隠すことなく、肉体のむき出しの物質性を、その最も屈辱的で哀れな側面で強調する哀愁をもって描かれている。レンブラントは、反骨精神に満ちた真実の誠実さ、そしておそらくは社会で恵まれない人々、老人、売春婦、酔っぱらい、乞食、障害者などへの同情心から、規則に反して自然に訴えかけている。聖書的なキリスト教感覚に染まっていた彼にとって、貧困や醜さは自然に内在するものであり、富や美しさと同様に注目に値するものだった。この啓示的な不完全さは、『水浴のダイアナ』(1631年)、『塚に座る裸婦』(1631年)、『クレオパトラ』(1637年)、『小川で足を洗う女』 (1658年)といった作品に顕著に表れています。また、 『ニコラース・トゥルプ博士の解剖学講義』 (1632年)では、人体解剖の最も粗雑な描写を厭いませんでした。さらに魅力的なのは、 『スザンナと長老たち』 (1634年)、『楽園のアダムとイブ』(1638年)、『牧神に見守られるバッカス』( 1636年 - 1647年、妻サスキア・ファン・ウイレンバーグを描いた)です。おそらく官能的な美を表現しようとした作品が、1654年の「浴場のバテシバ」である。この作品では、バテシバの恋人ヘンドリキエ・ストッフェルスが描かれている。丸みを帯びた寛大な体つきにもかかわらず、誠実に描かれたこの作品は、理想的ではないものの崇高な高貴さを伝えることに成功している。一方、瞑想的な表現は肉体的な姿に内なる生命を与え、魂の受け皿としての肉体というキリスト教の概念を反映した精神的なオーラを与えている。[110]

イタリアでは、建築家であり彫刻家でもあるジャン・ロレンツォ・ベルニーニの作品が有名です。彼はローマ教皇の栄華を豪華絢爛かつ雄弁に演出し、その作品はバロックの特徴である躍動的でしなやかな動きを表現しています。その特徴は、彼の主な彫刻群である「トロイから逃げるアエネアス、アンキス、アスカニオス」(1618–1619年)、「プロセルピナの略奪」(1621–1622年)、「投石器を投げるダビデ」 ( 1623–1624年)、 「時が明かす真実」(1645– 1652年)、「アポロとダフネ」(1622–1625年)に表れており、これらの作品では、彼の優れた造形技術、動きのドラマチックさ、大胆な短縮法、そして繊細なバランスで浮かんでいる祭服によく表れている装飾感覚が明らかです。もう一人の偉大な創造者はカラヴァッジョで、彼は厳密な自然現実に基づき、光と影の相互作用による劇的で驚くべき効果を生み出すためにキアロスクーロ(テネブリズム)の使用を特徴とする自然主義またはカラヴァジズムとして知られるスタイルを創始しました。奇抜で挑発的な芸術家であり、その作品の中で際立っているのは、洗礼者ヨハネ(羊を連れた若者)(1602年)、 「勝利のキューピッド」( 1602年 - 1603年)、 「キリストの埋葬」(1602年 - 1604年)、「キリストの鞭打ち」 (1607年)、「柱の前のキリスト」(1607年)、「書く聖ヒエロニムス」(1608年)、「ラザロの復活」(1609年)などである。彼の弟子には、ジョヴァンニ・バッティスタ・カラチョーロ(砂漠の若い聖ヨハネ、1610年 - 1620年、 「眠れるキューピッド」、1616年、「聖セバスティアヌスの殉教」、1625年)やアルテミジア・ジェンティレスキ(スザンナと長老たち、1610年、「ダナエ」、1612年、「クレオパトラ」、1621年、「ヨセフとポティファルの妻」、 1622年、『眠れる金星』 1625–30年)。[111]

イタリアとフランスの間では、古典主義と呼ばれる別の潮流が生まれました。これは同様に写実的ですが、より知的で理想化された現実の概念を持ち、神話のテーマはローマのアルカディアに匹敵する完全さと調和の世界を喚起しました。これはボローニャ派で、アンニーバレ・カラッチの手によって始まりました。彼のバッカスとアリアドネの勝利(1597年 - 1602年)には裸婦でいっぱいの行列が描かれており、これは彼がローマのファルネーゼ宮殿を手がけた装飾にも豊富に見られます。キリストの屍(1583年 - 1585年)は、マンテーニャの同名の作品にインスピレーションを得ています。この流派のもう一人の画家はグイド・レーニで、彼は『アタランテとヒッポメネス』(1612年)、 『ロバのあご骨から水を飲むサムソン』(1611年 - 1612年)、『デイアニラの略奪』(1620年 - 1621年)など、裸体によって尊厳と壮大さを際立たせた神や英雄の神話的寓話や絵画を数多く制作した。フランチェスコ・アルバーニは、神話の中に、彼が自然に好んでいた優雅で愛嬌のある主題を求めた。その例としては、連作『四季』(1616-1617年、 『冬』(ディアナの勝利)、『秋』 (ヴィーナスとアドニス)、『春』 (ヴィーナスの化粧』、『夏』 (ヴィーナスのウルカヌスの鍛冶場)、『素手の恋』(1621-1633年)、『メルクリウスとアポロン』 ( 1623-1625年)、『ディアナとアクタイオン』(1625-1630年)、『水の寓意』(1627年)などが挙げられる。グイド・カニャッチはこの流派の最後の代表者の一人で、古典主義をゲルマン圏に輸出した。『人生の寓意』、『クレオパトラの死』(1658年)、『聖ヒエロニムス』 (1659年)、『無意識のマグダラのマリア』(1665年)などである。[112]

フランスにおいては、静謐な古典主義の芸術家ニコラ・プッサンは、神話や古代史を主題とする博学な文化を絵画に表現し、教養と理想化を追求する点で、アカデミックな裸体画の創始者と言えるでしょう。ラファエル派の影響を受けた彼は解剖学にも関心を持ち、造形的かつ知的な視点から、すべての作品を丹念に作り上げました。考古学にも関心を持ち、クロード・ロランと共に、いわゆる「歴史的風景画」を創始しました。これは、風景画の枠の中に、古代の建築物や遺跡と共に、様々な歴史上または神話上の人物を配置する手法です。彼の作品には、アポロンとダフネ(1625)、アポロンとバッカス(1627)、エコーとナルキッソス(1628)、パルナッソス(1630)、ケパロスとオーロラ(1630)、ミダスとバッカス(1630)、フローラの帝国(1631)、ガラテイアの勝利(1634)、バッカス祭(1634–1635)、金の子牛の礼拝(1636)、ヴィーナスとアエネアス(1639)などがあります。[113]他の古典主義に影響を受けた芸術家は、シモン・ヴーエ(キューピッドとプシュケ、1626、眠れるヴィーナス、1630–1640)、シャルル・ル・ブラン(メレアグロスの死 、1658、ヘラクレスの功業、1658–1661)、ジャック・ブランシャール(『アンジェリカとメドーロ』 1630年、『ダナエ』 1630–1633年、『人間に驚かされるヴィーナスと三美神』 1631–1633年)。[114]

17世紀後半の「フル・バロック」様式では、光学的効果(トロンプ・ルイユ)と豪華で華麗な舞台美術を好んで、多くの芸術家がヴェルサイユ宮殿の装飾に携わり、この様式はフランス全土に広まりました。裸婦像は彫刻において特に発展し、フランス中の広場や庭園を埋め尽くしました。ピエール・ピュジェ( 『クロトーナのミロン』(1671-1682年)、『ペルセウスとアンドロメダ』(1685年))やフランソワ・ジラルドン(『ニンフに世話されるアポロ』(1666年)、『プロセルピナの略奪』(1677年))といった芸術家が活躍しました。彼は応用美術、特にブロンズや磁器、さらには彫刻や家具製作にも秀でていました。[115]

スペインは当時も芸術的に貞潔で慎み深い国であり、裸体像は慎み深いものとして捉えられていました。そのため、バルトロメ・エステバン・ムリーリョのような画家は、裸体像を幼児の姿でのみ描き、聖母マリアとその幼子イエス、そして聖母マリアのプットー、つまり作品の神聖な空間のいたるところで遊び、飛び回る小さな天使たちを描いた作品に多く登場させました。しかし、この頃からある種の開放性が始まり、教会関係者であったフアン・リジ修道士は、著書『賢明な絵画論』の中で裸体像の正当性を主張しました。この論の中で、彼は詳細な解剖学的研究を行い、自筆の多数の挿絵を添えています。[116]また、カルロス5世からフェリペ4世に至るまで、スペインの君主たちは裸体像の熱心な収集家であり、マドリード王宮の黄金の塔は、かつて真の裸体博物館であったことも特筆に値します。[117]

スペインにおける裸婦像は、フランシスコ・リバルタ、フセペ・デ・リベラ、フランシスコ・デ・スルバラン、グレゴリオ・フェルナンデス、ペドロ・デ・メナの作品に見られるように、依然として宗教的なテーマが主流であった。リベラの作品には、おそらくイタリア滞在の影響によると思われる、酩酊状態のシレノス(1626年)やアポロとマルシュアス(1637年)、イクシオン(1632年)とプロメテウス(1630年)の像、あるいはアロンソ・カノの「キリストの冥府への降下」(1646年 - 1652年)など、いくつかの例外が見られる。スルバランはまた、ベラスケスの依頼でパラダの塔のためにヘラクレスの絵を数枚描いている。[118]

しかし、スペイン・バロックの偉大な天才は、間違いなくフェリペ4世の画家ディエゴ・ベラスケスであり、彼の壮大な作品は美術史における画期的な作品の一つです。ベラスケスは、王室画家という立場から、制作において大きな自由を享受し、同時代の他のどのスペイン人画家よりも多くの裸婦像を描くことができました。しかし、聖職者による検閲の制約を受け、一部の作品では図像的な意味合いを変えざるを得ませんでした。神話的な裸婦像から、風俗画や衣装を題材とした場面へと変化していったのです。こうして、ディオニュソス的なテーマの酒宴となるはずだったものが『酒飲みたち』(1628-1629年)となり、マルスとビーナスの姦通を題材にした『ウルカヌスの鍛冶場』(1630年)が生まれました。[119]宗教画においては、論理的に問題が少ない。例えば『磔刑のキリスト』(1639年)や『鞭打ちの後のキリスト』(1632年) 、 『ヨセフのチュニック』(1630年)などでは、裸婦像に古典主義的、アカデミックな要素が色濃く表れており、このことは人物像の解剖学的概念にも表れている。ただし、後には服を着た姿で描かれる『糸紡ぎ』(1657年)では、システィーナ礼拝堂のミケランジェレスクの影響が顕著に見られる。[120]

しかし、セビリア出身の画家ベラスケスは、歴史上最も壮麗かつ有名な裸婦像の一つである『鏡のヴィーナス』(1647-1651年)で自らの探求に成功した。この作品は、当時としては珍しかった後ろ姿で描かれている点において、非常に独創的な裸婦像であり、その発想には、ベラスケスがイタリアで知っていたであろうボルゲーゼ美術館の『両性具有者』の影響が見て取れる。一方、鏡に映る自分を見つめるヴィーナスの姿勢は、おそらく虚栄心の寓意を表しているのだろう。この才気あふれる画家は、現在では失われている他の裸婦像も制作している。例えば、フェリペ4世が所有していた『キューピッドとプシュケ』や『ヴィーナスとアドニス』、ドミンゴ・ゲッラ・コロネル所有の女性裸婦像、そして画家自身が死去時に所蔵していた『横たわるヴィーナス』などである。[35]

-

横たわるキリスト(1634 年)、グレゴリオ・フェルナンデス作、バリャドリードのサン・ホアキン・アンド・サンタ・アナ王立修道院博物館。

ロココ

18世紀初頭にはバロック様式と、そして世紀末には新古典主義と共存しながら発展した[注8]。バロック様式の主要な芸術的表現が、より強調された装飾感覚と装飾趣味を伴って生き残ったことを意味しており、豊かさ、洗練、そして優雅さの爆発的な高まりを見せている。ブルジョワジーの社会的地位の向上と科学の進歩、そして啓蒙主義の文化的環境は、宗教的な主題を放棄し、新たな主題とより世俗的な態度を重視するようになり、贅沢さと虚飾が社会的威信の新たな要素として強調された[121] 。

この時代のヌードはルーベンスから受け継いだもので、特に肌の色彩と質感は彼から受け継がれ、よりエロティックな意味合いを帯びていた。洗練された宮廷風のエロティシズム、繊細で刺激的であるが挑発的である種の不遜さを伴い、古典主義的理想化の痕跡を一切放棄し、このジャンルの世俗的な性格を帯びていた。ヌードがより完全に発展したフランスでは、ルネッサンス期にもフランス美術から完全には消え去っていなかったゴシック様式の雰囲気が人物像に残っており、小さな胸と突き出た腹部を持つ細長い人物像に反映されている。19世紀半ばには、小柄で細身の人物像(プチ)がより人気となり、ブーシェの絵画作品(水浴びのディアナ)やクロディオンの彫刻作品(ニンフとサテュロス、犬と遊ぶ少女)に見ることができる。また、それまで卑猥だと考えられ、稀にベラスケスの『鏡の前のヴィーナス』やヴァトーの『パリスの審判』 、ブーシェの『休息する少女』などを除いてほとんど描かれていなかった背後からの裸婦も描かれるようになった。[122]

ジャン=アントワーヌ・ヴァトーは、この様式の創始者の一人であり、華やかな宴や田園風景を描いた作品には、神話上の人物、あるいはそうでない人物が人生を楽しむ姿が数多く描かれています。ルーベンスやヴェネツィア派の影響を受け、ヴァトーのパレットは鮮やかな色彩と、神経質で素早い、表現力豊かで躍動感あふれる筆致が特徴です。裸婦画は数少ないものの、それらは真に傑作であり、丹念な作風と卓越した優雅さで仕上げられています。 『パリスの審判』 (1718–1721年)に加え、 『泉のニンフ』(1708年)、『武器なき愛』(1715年)、『ユピテルとアンティオペ』(1715–1716年)、『水浴のディアナ』 (1715–1716年)、 『春』 (1716年)なども記憶に残る作品です。ヴァトーの弟子には、この巨匠の勇敢な作風を踏襲した芸術家が数多くいた。フランソワ・ルモワーヌ(『ヘラクレスとオンファレ』、1724年)、シャルル=ジョゼフ・ナトワール(『化粧をしたプシュケ』 、1735年)、ジャン・フランソワ・ド・トロイア(『ダイアナとニンフたちの水浴』、1722年–1724年、『スザンナと長老たち』、1727年)などである。[123]

フランソワ・ブーシェは、バロックの巨匠たちから学んだ遠近法を完璧にマスターし、ルーベンスやコレッジョの色彩表現を巧みに再現した。その作品は歴史画、肖像画、風景画、風俗画など、あらゆるジャンルに及んでいる。彼の絵画は牧歌的で田園的な雰囲気を漂わせ、しばしばオウィディウスの神話に触発されている。同時に、勇敢で宮廷的なセンスも持ち合わせており、流行画家、学者、そして国王の第一画家として高く評価された。彼の作品には、『休息する少女』(ルイ15世の愛妾マリー=ルイーズ・オマーフィーの肖像画。ブーシェが5姉妹全員を描いたが、その末っ子である。)のほか、『ヴィーナスの勝利』(1740年)、『レダと白鳥』(1742年)、『水浴後の休息するディアナ』(1742年)、『ヴィーナスの化粧』(1751年)などが特に有名である。[124]

弟子のジャン=オノレ・フラゴナールは、気品があり上品なカットの素晴らしいエロティシズムで、勇敢な愛の魅力をすべて表現する宮廷風のスタイルを継承した。彼はデュ・バリー夫人の弟子であり、夫人のために『恋の進展』 (1771–1773)という連作を制作した。これは5つの大きなパノー、「出会い」「追跡」「恋文」「満足した恋人」「見捨てられ」から構成されている。彼の他の作品には、『ヴィーナスの誕生』 (1753–1755)、『引き戻された変化』 (1761–1765)、『水浴者』 (1765)、『犬を連れた少女』 (1768)、『愛の泉』 (1785)、そしてレズビアンをテーマにした、より著しくエロティックな『二人の恋人』がある。[125]

彫刻の分野では、ロココ調の悪ふざけと勇ましい雰囲気と、17世紀のフランス彫像から受け継がれたある種の古典主義的雰囲気、そして肖像画への関心が融合した注目すべき裸婦像もありました。最も優れた代表例としては、ジャン=バティスト・ルモワーヌ(『水浴びから出るニンフ』)、エドメ・ブシャルドン(『ヘラクレスのメイスから弓を作るキューピッド』、1750年)、ジャン=バティスト・ピガール(『翼のあるサンダルをつけるメルクリウス』、1744年、『ヴィーナス』、1748年、『ヴォルテール』、1770~1776年)、エティエンヌ・モーリス・ファルコネ(『クロトーナのミロン』、1754年、 『ヴィーナス役のポンパドゥール夫人』 、1757年、『ピュグマリオンとガラテイア』、1763年)、ジャン=アントワーヌ・ウードン(『モルフェウス』、1770年、 『女狩人のダイアナ』、1776年、『冬の寓話』、1783年)、オーギュスタン・パジュ( 『捨てられたプシュケ』 、 (『ライン川を隔てる水』 1790年)とクロディオン(『ライン川を隔てる水』 1765年、『ガラテイアの勝利』1779年)。[126]

,_de_Juan_Carreño_de_Miranda..jpg/440px-La_monstrua_desnuda_(1680),_de_Juan_Carreño_de_Miranda..jpg)

フランス以外では、ヨーロッパの多くの地域でバロック様式は18世紀半ばまで存続したが、ロココ様式の隆盛に取って代わられるか、あるいはロココ様式と混ざり合った。バロック様式が生き残った明確な例は、フアン・カレーニョ・デ・ミランダの『裸の怪物』(1680年)である。ジャンバッティスタ・ティエポロは、豊かな色彩、澄んだ空、透き通った風景、荘厳な建築物、そして彼の作品に素晴らしい壮大さと華麗さを与えているある種の舞台美術的雰囲気を持つヴェネツィア派の追随者だった。彼の作品は寓話や歴史や神話のテーマが豊富で、『ダイアナがカリストの妊娠に気づく』(1720-1722年)のように神々や裸の英雄でいっぱいである。コラド・ジャクイントは、宗教画を好んでいたが、 『平和、正義、ヘラクレス』など裸の人物が登場する寓話や神話の絵画も制作した。スペインでは、マドリード王宮の柱廊の天井を、複数の裸神(アポロ、バッカス、ヴィーナス、ディアナ)で装飾しました。ドイツのアントン・ラファエル・メングスはすでに新古典主義を先導し、ミケランジェロの素描とラファエロの色彩、そしてコレッジョの明暗法を融合させようと試み、常に古代崇拝を背景にしていました。スペインに設立され、サンフェルナンド王立美術アカデミーの学長を務めた彼は、裸体表現における自然研究を提唱しました。マドリード王宮のガスパリーニ・ホール(1765-1769)の装飾では、ユピテルの前に立つヘラクレス、トラヤヌス帝の勝利、ユピテル、ヴィーナスと美の女神、オーロラなどの神々と古典的な英雄の本物のオリンポスを表現しました。ドイツでは、彫刻家ゲオルク・ラファエル・ドナー(アタランタ)とフランツ・イグナーツ・ギュンター(クロノス、1765-1770)も際立っていました。[127]

分類の難しい画家にフランシスコ・ゴヤがいる。彼はロココからロマン主義的精神の表現主義へと進化した無比の天才だが、その個性が作品に美術史上比類のない独自の個性を与えている。裸婦画における彼の最高傑作は『裸のマハ』 (1797-1800年)で、 『服を着たマハ』 (1802-1805年)と並行して描いたもので、陰毛がはっきりと見える最初の裸婦画のひとつである。[128]これは歴史的、神話的、宗教的な主題に正当化されない最初の裸婦画のひとつであり、単に匿名の裸婦が描かれ、[注 9]親密な雰囲気を漂わせながら、ある種ののぞき見するような雰囲気を漂わせている。これは誇り高く、ほとんど反抗的な裸婦画であり、マハはいたずらっぽく遊び心のある様子で私たちをまっすぐに見つめ、見る者の歓喜にその肉体のしなやかな美しさを披露している。アラゴン出身の天才が初期に制作した裸婦画には、他に『ピエタ』(1774年)、『十字架にかけられたキリスト』(1780年)、『プシュケとキューピッド』(1798年~1805年)、『女を裸にする盗賊』(1798年~1800年)などがある。[129]その後、聴覚障害、個人的な不幸、宮廷生活の倦怠感、戦争の恐怖、亡命生活、孤独、老齢といった様々な要因が、彼の人格と作品に影響を与え、より表現力豊かで内省的になり、強い風刺性と醜悪な美的感覚を帯びるようになり、周囲の人々と世界の最も過酷で残酷な側面を浮き彫りにするようになった。この時期の彼の裸婦像は、より劇的で、時に哀愁を帯び、奇形で荒々しい肉体を特徴としている。例えば、『魔女の台所』(1797–1798)、『斬首』(1800–1805)、『狂気の館』(1812–1819)、『焚き火』(1812–1813)や、残忍な『我が子を食らうサトゥルヌス』(1819–1823)などが挙げられる。その後、彼は彫刻に力を入れ、苦悩する内面を理想的に捉える手段を得た。『戦争の惨劇』 (1810–1815)などの連作には、主に死体を描いた裸婦像がいくつかある。例えば、『Se aprovechan(邦題:死の試練)』、『Esto es peor (邦題:この男は) 』、『¡Grande hazaña! ¡Con muertos!(邦題:死者と共に! )などである。あるいは『ロス・カプリチョス』(1799年)では、「ミレン・ケ・グレイブス!」、「セ・レピュレン」、「クイエン・ロ・クレイエラ!」、「ソプラ、アグアルダ・ケ・テ・ウンテン、シ・アマネス、ノス・ヴァモス、リンダ・マエストラ、アッラー・ヴァ・エソ、¿ンデ・ヴァ・ママ?」のように、魔女や他の同様の存在の服を脱がせる。、等[130]

-

ジャン=アントワーヌ・ヴァトーの「春」(1716年)が破壊された。

-

フランソワ・ブーシェ作「水浴後の休息をとるダイアナ」(1742年)、ルーブル美術館、パリ。

-

「水浴びする人たち」 (1765 年)、ジャン=オノレ・フラゴナール作、ルーヴル美術館、パリ。

-

ヴォルテール(1776 年)、ジャン・バティスト・ピガール作、ルーヴル美術館、パリ。

新古典主義

フランス革命後のブルジョワジーの台頭は、貴族階級を象徴するバロックやロココの装飾過多とは対照的に、より純粋で簡素な古典様式の復活を促した。こうした古典ギリシャ・ローマ遺産への評価の風潮は、ポンペイとヘルクラネウムの考古学的発見、そしてヨハン・ヨアヒム・ヴィンケルマンによる古典様式の完全性というイデオロギーの普及に影響を受けた。ヴィンケルマンは古代ギリシャには完全な美があったと仮定し、古典美の完全性に関する神話を生み出した。この神話は、今日に至るまで芸術の認識を規定している。[注 10]

新古典主義の裸婦像は、古代ギリシャ・ローマの形態を回復したものの、その精神、理想性、模範的な精神を失って、純粋な形態のみで、人生から遊離した形で自らを再現しようとした。その結果、冷淡で冷徹な芸術が生まれた。この芸術は、ほとんど反復的な回帰感覚を伴いながらアカデミズムの中で長期化していくことになる。古典の研究は、芸術家自身の個性的な表現を阻害する。これは、最初の破壊運動である印象派以来、芸術の前衛精神によって闘われてきた。ジロデやプリュードンといったこの時代の芸術家たちの作品には、特にコレッジョの影響により、古典主義とある種のマニエリスムの奇妙な融合が見られる。彼らは古き古典主義の復興を志向しながらも、文脈から切り離され、時代を超越した作品を生み出した。[131]

ジャック=ルイ・ダヴィッドは、新古典主義の推進力となった人物です。一見アカデミックな作風でありながら、情熱的で才気溢れる作風で、知的な節度を保ちながらも美しく色彩豊かな表現を妨げませんでした。画家であると同時に政治家でもあった彼は、新古典主義を擁護し、革命期およびナポレオン期のフランスにおける美的潮流を築きました。1775年から1780年にかけてローマに滞在し、古代彫刻家ラファエロやプッサンに影響を受け、厳格で均整のとれた、高度な技術的純粋さを備えた古典主義へと導かれました。彼の作品の中でも特に有名なのは、『パリスとヘレネの恋』(1788年)、『マラーの死』(1793年)、『サビニの女たちの介入』(1799年)、『テルモピュライのレオニダス』(1814年)、『キューピッドとプシュケ』 (1817年)、 『ヴィーナスに武装解除されるマルス』(1824年)などです。[132]

ダヴィッドの弟子や信奉者たちは、彼の古典的な理想を継承しつつも、その厳格な厳格さから離れ、ある種の官能主義的なマニエリスムへと傾倒していった。マックス・フリードレンダーはこれを「ヴォリュプテ・デセント(適切な官能性)」と呼んだエロティックな優美さを帯びていた。 [133] フランソワ・ジェラールは、柔らかな色彩と青い肌の質感、大理石模様でありながらも柔らかく、シロップのような甘さを持つ体を通して、理想的な美の完成を追求した。彼の最も有名な作品は『プシュケと愛』(1798年)で、アカデミズム的な技巧を凝らしながらも、色彩の豊かさが洗練された叙情的な情感を呼び起こす。ピエール=ナルシス・ゲランもまた、コレッジョの影響を受けた洗練されたエロティシズムを育み、『オーロラとケファロス』(1810年)や『イリスとモルフェウス』(1811年)に見られるように。ジャン=バティスト・ルニョーは、ボローニャ派に近い古典主義路線を開拓した。『自由と死の間のフランスの天才』(1795年)では、天才がラファエロの『ヴァチカンのスタンザ』のメルクリウスを想起させる。ダヴィッドの他の弟子には、ジャン・ブロック(『ヒュアキントスの死』、1801年)とジャン=ルイ・セザール・レール(『プロメテウスの拷問』、1819年)がいる。一方、アンヌ=ルイ・ジロデ・ド・ルシー=トリオゾンは、特に彼女の主力作『エンデュミオンの眠り』 (1791年)で、細長く真珠のような体とある種の性的曖昧さを特徴とし、イタリアのマニエリスムやアール・ポンピエの前奏曲を思わせるややぼんやりとした雰囲気を漂わせながら、ダヴィッドの道徳的古典主義を破った。その他の作品には、『ヴィーナス役のマドモアゼル・ランゲ』(1798年)、『ダナエ役のマドモアゼル・ランゲ』(1799年)などがある。[134]ピエール=ポール・プリュードンはロココと新古典主義の中間に位置する画家であり、ダヴィッドは彼を軽蔑的に「同時代のブーシェ」と呼んだ。今でも彼をロマン派と呼ぶ人もいる。彼はローマで教育を受け、そこでレオナルドとコレッジョの影響を受け、古典美術と共に彼の作風の基礎を築き、独自の個性を育んだ。だからこそ、彼は分類が難しい画家なのだ。彼の作品の中では、『正義と神の復讐は罪を追う』(1808年)、『ゼピュロスによるプシュケの誘拐』(1800年)、『ヴィーナスとアドニス』(1810年)などが記憶に残る。[135]

ダヴィッドが新古典主義の巨匠の傑作だとすれば、彫刻界における彼の比肩する人物はアントニオ・カノーヴァです。彼はルネサンスの巨匠たち(ギベルティ、ドナテッロ、ミケランジェロ)の作品を学びましたが、インスピレーションの源は、故郷イタリアの偉大なコレクションを通して得た、古典的なギリシャ・ローマ彫刻でした。そのため、彼の作品は、純粋な古典主義の静謐さと調和を備えながらも、イタリアの祖先に特徴的な人間的な感受性と装飾的な雰囲気を確かに示しています。作品には『ダイダロスとイカロス』(1777–1779)、『テセウスとミノタウロス』(1781–1783)、『キューピッドの接吻で蘇るプシュケ』(1786–1793)、『ヴィーナスとアドニス』(1789–1794)、『ヘラクレスとリカス』(1795–1815)、『勝利のペルセウス』(1800)、『平和の使者マルスとしてのナポレオン』 ( 1803–1806)、『勝利のヴィーナスとしてのポーリーヌ・ボナパルト』(1804–1808)、『ケンタウロスと戦うテセウス』(1804–1819)、『三美神』(1815–1817)などがある。[136]

もう一人の傑出した彫刻家はデンマークのベルテル・トルヴァルセンです。高貴で静謐な古典主義にもかかわらず、冷たく計算された制作手法は一部の批評家から評価を下げ、作品を味気なく空虚だと批判されました。それでもなお、生前は大きな成功を収め、故郷のコペンハーゲンには彼のための美術館が建てられました。トルヴァルセンは、ミュンヘンのグリプトテークに収蔵される前のアイギナ島のアファイア神殿のペディメントの修復を通して、ギリシャ彫刻を直接学びました。彼の最も有名な作品は、ポリュクレイトスの『ドリフォロス』に触発された『金羊毛のイアソン』 (1803–1828)であるが、他の作品には『キューピッドとプシュケ』(1807)、『マルスとキューピッド』 (1812 )、『リンゴとヴィーナス』 (1813–16)、 『光の精霊とオーロラ』 (1815) 、『ヘーベ』(1815)、『木星の鷲とガニメデ』(1817)、『キューピッドと三美神』 (1817–1818)などがある。[137]

もう一人の著名な彫刻家は、イギリス人の ジョン・フラックスマンである。彼は10歳にしてすでに彫刻を制作していた早熟の芸術家であり、芸術家としても、学術論文執筆者としても実りある経歴の持ち主で、『彫刻と解剖学に関する10の論考』など、彫刻の実践に関するいくつかの著作を残している。彼の作品には、『ケパロスとオーロラ』(1790年)、『アタマスの怒り』(1790年 - 1794年)、『メルクリウスとパンドラ』(1805年)、『蠍座に犯されるアキレウス』(1810年)、『悪魔に打ち勝つ聖ミカエル』(1818年 - 1822年)など、多数の裸婦像がある。さらに、彼は優れた製図家および彫刻家でもあり、線を引く技巧と美しい横顔の持ち主で、数多くの古典文学作品を巧みに図解した。[138]ゲルマン民族にも注目すべき彫刻の流派が発達し、フランツ・アントン・フォン・ツァウナー(『天才ボルニイ』、1785年)、ルドルフ・シャドウ(パリ、1812年)、ヨハン・ハインリヒ・ダネッカー(『豹のアリアドネ』 、1812年~1814年)、ヨハン・ネポムク・シャラー(『キマイラと戦うベレロフォン』 、1821年)などがその代表的人物である。

スペインでは、新古典主義は、エウセビオ・バルデペラス(『スザンナと長老たち』)やディオスコロ・テオフィロ・プエブラ( 『ラス・ヒハス・デル・シド』、1871年)などの数人の学術画家によって実践され、新古典主義の彫刻家にはホセ・アルバレス・クベロ(ガニメデ、1804年、アポリノ、1810~1815年、1810~1815年)が含まれる。ネストルとアンティロコス[またはサラゴサの防衛]、1818)、フアン・アダン (アラメダのヴィーナス、1795)、ダミア・カンペニー(入浴中のダイアナ、1803;瀕死のルクレティア、1804;かかとから矢を抜くアキレス、1837)、アントニ・ソラ (メレアグロ、 1818)、サビノメディナ(エウリュステウスから逃げる途中にアスプに噛まれたニンフ・エウリュディケ(1865年)、ジェロニモ・スニョル(ヒメナエウス、1864年)など[139]

-

エンディミオンの夢(1791 年)、アンヌ・ルイ・ジロデ・ド・ルシー・トリオソン作、ルーヴル美術館、パリ。

-

フランソワ・ジェラール作「プシュケと愛」(1797年)、ルーブル美術館、パリ。

-

黒人女性の肖像(1800 年)、マリー・ギルミーヌ・ブノワ作、ルーヴル美術館、パリ。

-

プロメテウスの拷問(1819 年)、ジャン・ルイ・セザール・レア作、クロザティエ美術館、ル・ピュイ・アン・ヴレ。

現代美術

19世紀

18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけて、現代社会の基盤が築かれました。政治面では、フランス革命を契機とした絶対主義の終焉と民主主義政府の樹立、経済面では産業革命と資本主義の強化が顕著で、これはマルクス主義と階級闘争という形で呼応することになります。芸術の分野では、様式の進化のダイナミズムが時系列的に加速的に進行し、20世紀には様式と潮流が細分化され、共存し、対立し、影響し合い、対峙するようになりました。アカデミックな芸術とは対照的に、近代美術が誕生し、芸術家は人類の文化的進化の最前線に立つこととなりました。[140]

19世紀のヌードは、それ以前の様式によって定められたヌード表現のガイドラインを踏襲していますが、より写実的な表現を目指すか、古典的ルーツに根ざした理想主義を目指すかによって、様々な解釈がなされています。19世紀、特に19世紀後半には、美術史における他のどの時代よりも、女性のヌードがかつてないほど豊富に描かれました。しかし、女性の役割は変化し、性欲の対象としてのみ捉えられるようになり、マッチョ社会の支配下で女性像は非人間化されていきました。これらの作品には強い盗み見的な側面があり、女性は眠っている時や身繕いをしている時に驚かされます。親密な場面でありながら、鑑賞者に開かれており、鑑賞者は禁断のイメージ、盗み見た瞬間を思い浮かべながら、その姿を再現することができます。これは計画的なヌードでも、モデルのポーズでもなく、日常生活の場面を、一見自然に見えるものの、作者によって無理やり再現されたものです。カルロス・レイエロの言葉を借りれば、「私たちは裸の女性たちではなく、服を脱がされた女性たちと出会うのです」[注 11] [141]

ロマン主義

あらゆる芸術ジャンルにおける根本的な革新運動であったロマン派は、精神性、想像力、幻想、感情、夢想、自然愛といった領域に特別な関心を寄せました。同時に、より暗い非合理性、オカルティズムへの傾倒、狂気、夢といった要素も重視しました。特に重視されたのは、大衆文化、異国情緒、そして過小評価されてきた過去の芸術形式、とりわけ中世の芸術形式への回帰でした。ロマン派は、個人から自発的に生じる芸術という概念を抱き、「天才」の姿を強調しました。芸術とは芸術家の感情の表現である、と。[142]ロマンティックな裸婦像はより表現力豊かで、新古典主義とは異なり、人物の線よりも色彩に重点が置かれ、より劇的な感覚で描かれ、異国情緒や東洋趣味から、ドラマ、悲劇、英雄的で情熱的な行為、高ぶった感情、自由への歌、人間の内面の純粋な表現まで、さまざまなテーマが描かれています。[141]

ロマン主義には、イギリスに二人の著名な先駆者がいた。ヨハン・ハインリヒ・フュスリとウィリアム・ブレイクである。スイス出身のフュスリは、デューラー、ポントルモ、バッチョ・バンディネッリ、ミケランジェロの影響を受けたマニエリスム様式を展開し、エロチックで暴力的なテーマと、ルソーの影響を受けた美徳と簡素さという、ある種の概念的二重性の作品を制作した。 1770年から1778年にかけて、彼は「シンプルグマ(絡み合う素描)」と呼ばれるエロティックなイメージの連作を制作した。そこではセックスは情熱と苦しみと関連付けられており、古代のバッコスの儀式や男根の儀式を想起させる版画に、ロココ調の勇敢さとはかけ離れた粗野で写実的なエロチシズムが表れている。彼の作品には、ハムレット、ホレイシオ、マルセラスと幽霊(1780–1785)、ティターニアとボトム(1790)、横たわる裸婦とピアノを弾く女(1800)および羽根飾りの娼婦(1800–1810)などがある。[143] ウィリアム・ブレイクは幻想的な芸術家であり、その夢のような作品はシュルレアリスムの幻想的な非現実性に匹敵する。芸術家で作家の彼は、自分の文学作品や『神曲』(1825–1827)や『ヨブ記』(1823–1826)などの古典に、夢と感情に満ちた自分の内面世界を表す独自のスタイルで挿絵を描いた。その挿絵は、一般に夜間の、物理法則に従わない空間に漂っているように見えるはかない人物や、冷たく流動的な光、豊富なアラベスク模様などである。ミケランジェロとマニエリスムの影響を受け、彼の人物像はミケランジェロ風の『最後の審判』のような躍動感に溢れているが、時には古典的な規範に基づいている。例えば『アルビオンの踊り(喜びの日)』(1794-1796年)では、その姿勢は『普遍建築の理念』に登場するヴィンチェンツォ・スカモッツィの『ウィトルウィウス的人体図』の版から取られている。彼の他の作品には、『ネブカドネザル』 (1795年)、『ニュートン』(1795年)、『アフリカとアメリカに支えられたヨーロッパ』 ( 1796年)、『本来の栄光のサタン』(1805年)、『恋人の旋風』、フランチェスカ・ダ・リミニとパオロ・マラテスタ(1824-1827年)などがある。[144]

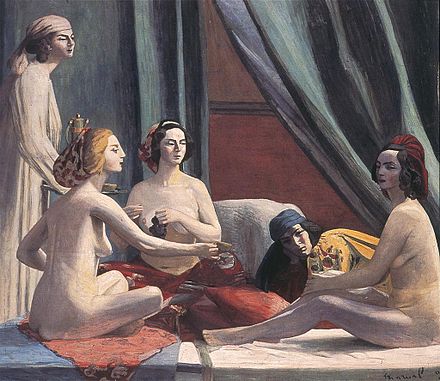

新古典主義とロマン主義の中間に位置するのがジャン・オーギュスト・ドミニク・アングルの作品である。アングルの人物像は官能性と純粋な形態へのこだわりの中間にあり、アングルはその両方を細心の注意を払って、ほとんど頑固とも言えるほどに扱っている。アングルの女性像にはゴシック風の雰囲気(小さな胸、突き出た腹部)があり、アングルが心地よく感じ、生涯を通じて繰り返し採用した少数の姿勢デザインに従っている。例えばその 1 つが仰向けに座る裸婦の像で、アングルは『ヴァルパンソンの水浴女』 (1808 年)で導入し、 『トルコ風呂』の集団場面の中に見ることができる。もう 1 つはボッティチェリ風の立ち姿のウェヌス・アナデュオメネ(1848 年)で、アングルはこれをベースとした複数のバージョンを制作し、後に水差しを持った若い女性の『泉』(1856 年)に作り変えている。その他の作品はより個人的なもので、例えば「グランド・オダリスク」 (1814年)はフォンテーヌブロー派のマニエリスムを想起させ、東洋主義、異国情緒あふれる人物や環境への傾倒のきっかけとなった。黄金時代(1840-1848年)には、裸婦のみで構成された大壁画を制作したが、未完成に終わった。「トルコ風呂」(1862年)はおそらく彼の最も有名な作品であり、生涯をかけた裸婦研究の集大成と言えるだろう。彼は東洋主義に戻り、ハーレムを舞台にした作品を制作した。この作品では、モデルの曲線美と丸みを強調し、豊かな胸と広い腰を恥ずかしげもなく見せ、当時の西洋美術では異例の官能性を見せている。その他の作品としては、『アガメムノンの使者』(1801年)、『オイディプスとスフィンクス』(1808年 - 1825年)、『ジュピターとテティス』 ( 1811年)、『オシアンの夢』(1813年)、『アンジェリカを解放するロジャー』(1819年)、『奴隷とオダリスク』(1842年)などがある。[145]

彼の弟子には、ナポレオンの功績の記録者アントワーヌ=ジャン・グロがおり、グロは『ヤッファのペスト患者を見舞うボナパルト』(1804年)の中で、病気の影響を粗野に描いた強烈なドラマチックなヌードをいくつか制作した。また、アングルの作風とドラクロワの色彩感覚を融合させようとしたが、作品はアカデミズムに傾倒していたテオドール・シャセリオー( 『アナディオメネのヴィーナス』(1838年) 、 『スザンナと長老たち』(1839年)、『アクタイオンに驚かされるダイアナ』(1840年)、『ネレイデスに岩に鎖でつながれるアンドロメダ』 (1840年)、 『エステルの化粧』(1841年) 、 『眠れるニンフ』 (1850年) 、『テピダリウム』(1853年)などである。[146] テオドール・ジェリコーはミケランジェロの影響を受けており、システィーナ礼拝堂の運動選手の一人である『メデューズ号の筏』 (1819年)の中央人物像にそれが見て取れる。また、他の人物像はラファエロの『変容』の人物像を彷彿とさせる。ジェリコーは解剖学の研究のため、遺体安置所や囚人が処刑される刑務所を頻繁に訪れた。『レダと白鳥』(1822年)では、古代の運動選手の躍動感を女性像に描き出しており、その姿勢はパルテノン神殿のイリュソスを彷彿とさせ、運動能力を性的興奮へと転換させている。[147]

.jpg/440px-Delacroix_-_La_Mort_de_Sardanapale_(1827).jpg)

ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワは、公式のアカデミック美術から逸脱した最初の画家の一人で、輪郭線によるデッサンを、より正確性に欠け、流動的で、躍動的で示唆に富んだ線、鮮やかな隣接色調による色彩主義、そしてある種の色彩分割主義に基づく効果性へと置き換えた。修行中、ルーヴル美術館に展示されていた巨匠の作品の模写をしており、ルーベンスやヴェネツィア派の画家への偏愛が目立った。初期作品である『地獄のダンテとウェルギリウス』(1822年)、『キオス島の虐殺』 (1824年)、『サルダナパールの死』(1827年)において、すでに独創性と発明の豊かさ、そして後に彼を特徴づける情熱的で色彩豊かな作風が見られた。1832年にはモロッコとアルジェリアを旅し、異国情緒と細部へのこだわりを持つ東洋主義の影響を自身の作風に取り入れた。彼の多数の裸婦作品の主題は非常に多様で、宗教的なもの(アダムとイブの楽園追放、円柱のキリスト、十字架上のキリスト、復活したキリスト、聖イレーネと侍女に世話される聖セバスティアヌス)、神話的なもの(アポロンの勝利、ヘラクレスの二百年の冒険、アキレウスとケンタウロス、アナクレオンと愛、アンドロメダとペルセウス、アリアドネとテセウス、メディアとその子供たち)、歴史的および文学的なもの(神曲、マルフィセ、解放されたエルサレム)、風俗画や裸婦そのもの(オダリスクの横臥、水浴びをするトルコ人女性、絹のストッキングをはいた女性、髪を梳かす女性、仰向けになって水浴びをする女性、眠るニンフ、オウムを撫でる女性)などがあります。ドラクロワにとって、肉体的な美を表現するにはどんな口実でも良いことだった。例えば、民衆革命を率いるヒロインが胸を露わにした『民衆を導く自由の女神』 (1830年)の寓意画がそうだ。優れたデッサン家でもあった彼は、裸体像の素描や下絵を数多く残している。[148]

ドラクロワの後継者には、ナルシス・ヴィルジル・ディアス・デ・ラ・ペーニャ、風景画の巨匠で『妖精の池』『ヴィーナスとアドニス』『森のニンフ』『戒められ武装解除された愛』などの裸婦画の作者。ギュスターヴ・ドレ、主に文学作品のデッサン家および挿絵画家として優れ、聖書や『神曲』『狂えるオルランド』、シェークスピアの 戯曲、ゲーテの 『ファウスト』などで想像力と造形力の高さを示した。フェリックス・トゥルタ、彼の『豹の皮を被った裸婦』(1844年)はゴヤの 『裸のマハ』を彷彿とさせ、マネの『 オランピア』に先行する作品である。[149]

彫刻において、フランソワ・リュードは新古典主義からロマン主義へと発展し、裸婦が主役を務める表現力豊かな作品を生み出した。巨大な人物像は、その構造において動作のダイナミズムを表現している。その例としては、メルクリウスがかかとに翼をつける(1827年)、カメと遊ぶ若いナポリの漁師(1833年)、勝利の愛(1855年)、ヘーベと鷲(1855年)、そしてパリの凱旋門にある主作ラ・マルセイエーズ(1833年)が挙げられる。ジャン=バティスト・カルポーも同様の様式的変化を示し、古典的な静寂からロマン主義へと移行した。その強烈なダイナミズムを表現する人物像としては、チュイルリー宮殿の植物相(1865年)、ウゴリーノとその息子たち(1863年)、パリ・オペラ座のダンス集団(1869年)などが挙げられる。[150]

イタリアでは、ナポレオンの征服とともにロマン主義が到来し、ペラージョ・パラージ(『キューピッドとプシュケの婚約』、1808年)やフランチェスコ・アイエツ(『懺悔するマグダラのマリア』 、1825年)といった芸術家が活躍した。彫刻においては、ロレンツォ・バルトリーニが古典主義から自然主義へと発展し、フィレンツェの18世紀末期の塑像に触発された作品『神への信頼』 (1835年)を制作した。もう一人の代表例はジョヴァンニ・デュプレ(『アベルの死』 、1842年)である。[151]

スペインでは、エウジェニオ・ルーカスが描いた2枚の裸のマハスや、ホセ・グティエレス・デ・ラ・ベガ(『裸のマハ』、1840年 - 1850年)、アントニオ・マリア・エスキベル(『解剖されたヴィーナス』 、1838年、『スザンナと長老たち』、1840年、『ヨセフとポティファルの妻』、1854年)、ビクトル・マンサノ(『異端審問の場面』、1860年)などの作品に見られるように、ロマン主義にゴヤの影響が浸透していた。彫刻では、メキシコに拠点を置いたスペイン人マヌエル・ビラールが『イアソン』(1836年)や『メキシコのヘラクレス』とも言うべき『トラウイコレ』(1851年)を制作した。[152]

-

悔い改めのマグダラ(1825 年)、フランチェスコ・ヘイズ作、ミラノ市立近代美術館。

-

ヒョウの皮をかぶった裸の少女(1844 年)、フェリックス・トルタ作、ルーヴル美術館、パリ。

アカデミズム

.jpg/440px-Hypatia_(Charles_William_Mitchell).jpg)

アカデミック芸術とは、16世紀以降、芸術家の教育訓練を統制していた美術アカデミーによって推進されてきた芸術です。 [注12 ]アカデミーは原則として当時の芸術と調和していたため、明確な様式を語ることはできません。19世紀、様式の進化のダイナミズムが古典主義の規範から離れ始めると、アカデミック芸術は厳格な規則に基づく古典主義様式に閉じ込められました。そのため、今日ではアカデミック芸術は19世紀の一時代として理解され、フランスのアール・ポンピエなど、様々な呼称が並行して受け継がれています。[注13]アカデミズムは主にブルジョア階級を対象としていたため、「公式」芸術としての地位と、芸術は教えられないというロマンチックな考えに基づく保守主義や想像力の欠如という非難が相まって、19世紀末にはアカデミズムは過去に縛られ、陳腐な定型を繰り返すものと見なされ、軽蔑的な意味合いを帯びるようになった。[注14]

しかし、今日ではアカデミック芸術を再評価し、その本質的な性質を重視する傾向があり、様式としてよりもむしろ芸術の一時代として捉えられることが多い。アカデミズムは様式的にはギリシャ・ローマ古典主義を基盤としていたが、ラファエロ、プッサン、グイド・レーニといったそれ以前の古典主義の画家たちの作品にも影響を受けている。技術的には、丁寧なデッサン、形式的なバランス、完璧な線、造形の純粋さ、そして緻密なディテール、そして写実的で調和のとれた色彩を基盤としていた。彼らの作品は、歴史、神話、学術文献といった学問的なテーマと、理想化された美の概念に基づいていた。[153]

アカデミズムにおいて、裸体は特別な意味を持ち、自然の高貴さを最もよく表現するものと考えられていました。ポール・ヴァレリーの言葉を借りれば、「物語作家や詩人にとっての愛が、この形式の芸術家にとっての裸体であった」のです。[154]アカデミズムにおける裸体とは、厳格な主題と形式上の規則に服従する古典的な前提に基づく標準化を意味し、19世紀社会の概して清教徒的な環境に従属していました。裸体は理想的な美の表現としてのみ受け入れられ、解剖学的研究に厳密に基づいた、控えめで無菌的な裸体でした。古典的な裸婦像が美の理想の表現として受け入れられたことで、古典主義の規範からの逸脱はすべて検閲されるようになった。例えば、1851年のロンドン万国博覧会では、有名な水晶宮が大理石の裸婦像のギャラリーで飾られたが、ハイラム・パワーズの「ギリシャの奴隷」を除くすべての裸婦像が受け入れられた。「ギリシャの奴隷」はクニドスのアフロディーテの模写であるにもかかわらず、手首に手錠をかけられていることで批判された。しかし、デッサン学校で実践されていた教育実践によって、場合によっては形式や様式に目新しいものが導入され、このジャンルが活性化し、同時に知的な精緻化の産物としてより大きな尊敬を集めることになった。[155]

_-_01.jpg/440px-Jean-Léon_Gérôme,_Phryne_revealed_before_the_Areopagus_(1861)_-_01.jpg)

アカデミックな裸体画の中心はアングルの作品であった。ヴィンケルマンの理論によれば、男性の裸体は性格しか表現できず、女性の裸体だけが美しさを反映できる。美しさは柔らかくしなやかな形態でより明確に表現されるからである。アングルの裸体画は、人物像に丸みを帯びたフォルム、滑らかな質感、そして柔らかな輪郭を与える筆致の連続性を反映していた。結果として、アカデミック美術は男性よりも女性の裸体画に重点を置き、滑らかな形態と蝋のような質感を持つ人物像を描いた。[156]

アカデミズムの代表的な画家のひとりにウィリアム・アドルフ・ブグローがいます。彼は、一般に神話を題材にした裸婦像を多数制作しました。人物は解剖学的に非常に完璧で、青白く、髪が長く、官能的な雰囲気を漂わせる優雅な身振りをしています(『ヴィーナスの誕生』 1879年、『夜明け』 1881年、『波』 1896年、『オレイアス』1902年)。もうひとりの代表例としてアレクサンドル・カバネルがいます。彼は官能的で官能的な美しさを持つ女性を表現する口実として、神話的、寓話的な裸婦像を制作しました。たとえば有名な『ヴィーナスの誕生』 (1863年)などです。ウジェーヌ・エマニュエル・アマウリ=デュヴァルも同様で、同じく『ヴィーナスの誕生』(1862年)を制作しました。ジャン=レオン・ジェロームは、純粋なアングル様式でハーレムやトルコ式浴場を舞台にした作品や、神話や歴史を題材にした作品(『アレオパゴスの前のフリュネ』、1861年、『ムーア人の浴場』、1870年、『ハーレムの池』、1876年、『ピグマリオンとガラテイア』、1890年)で、アカデミックな東洋主義を代表する画家の一人です。その他の画家としては、フランソワ=レオン・ベヌヴィル(『アキレスの怒り』1847年)、オーギュスト・クレサンジェ(『蛇に噛まれた女』1847年、『レダと白鳥』1864年)、ポール・ボードリー(『真珠と波』1862年)、ジュール・ジョゼフ・ルフェーブル(『真実』1870年、 『洞窟の中のマグダラのマリア』 1876年)、アンリ・ジェルヴェックス(『ローラ』1878年)、エドゥアール・ドゥバ=ポンサン( 『ハマムのマッサージ』1883年)、アレクサンドル・ジャック・シャントロン( 『ダナエ』1891年)、ガストン・ビュシエール(『ネレイス』1902年)、ギヨーム・セニャック(『プシュケの目覚め』1904年)などが挙げられる。 [141]

イギリスでは、ヴィクトリア朝社会がアカデミズムを、ブルジョワジーと貴族の間で広まっていた清教徒的道徳を最もよく表現する公式の芸術として奨励し、ジョセフ・ノエル・パトン(『オーベロンとティターニアの口論』、1846年)、チャールズ・ウィリアム・ミッチェル(『ヒュパティア』、1885年)、フレデリック・レイトン( 『水浴のプシュケ』、1890年)、ジョン・コリアー(『リリス』、1887年、『ゴディバ夫人』、1898年、『ヴィーナスベルクのタンホイザー』、1901年)、エドワード・ポインター(『ディアデュメネ』、1884年、 『嵐のニンフの洞窟』、1903年)、ローレンス・アルマ=タデマ(『愛用の習慣』、1909年)、ジョン・ウィリアム・ゴッドワード(『水浴のヴィーナス』、1901年、『テピダリウムにて』、 1913年の『裸婦』、 1922年の『浜辺の裸婦』、ハーバート・ジェームズ・ドレイパー(『ユリシーズとセイレーン』、1909年)など。

スペインでは、ルイス・リカルド・ファレロも女性像に特別な愛着を持っており、幻想的な要素と東洋主義的なテイストが際立つ作品を残している。『東洋美人』 (1877年)、『ファウストの幻影(安息日に向かう魔女たち)』(1878年)、『魔女』 (1878年)、 『ポーズ』 (1879年)、『寵児』 (1880年)、『双子の星』(1881年)、『百合の精』(1888年)、『蝶』(1893年)などである。

-

真実(1870年)、ジュール・ジョゼフ・ルフェーブル作、オルセー美術館、パリ。

-

安息日に向かう魔女たち(1878年)、ルイス・リカルド・ファレロ作。

-

ネレイス(1902年)、ガストン・ビュシエール作、個人所蔵。

-

Les Oréades (1902)、ウィリアム アドルフ ブーグロー作、個人コレクション。

-

「オダリスク」(1902-1903年)、ジャクリーヌ・マルヴァル作、グルノーブル美術館。

-

嵐のニンフの洞窟(1903年)、エドワード・ポインター作、個人所蔵。

リアリズム

,_Paris,_Petit_Palais.jpg/440px-Gustave_Courbet_-_Le_Sommeil_(1866),_Paris,_Petit_Palais.jpg)

19世紀半ば以降、現実を強調し、産業革命という新たな枠組みの中で、特に労働者や農民といった周囲の世界を描写する傾向が生まれた。そこには、ユートピア社会主義などの政治運動や実証主義などの哲学運動と結びついた、ある種の社会的非難の要素が込められていた。19世紀前半に古典芸術理論が崩壊する中で、リアリズムは、多くの新進芸術家にインスピレーションを与えた写真技術の出現による技術的解放と相まって、主題の解放を意味した。そこでは、主人公はもはや貴族や英雄や神ではなく、路上の普通の人々であり、その悲惨さと粗野さをすべて描き出していた。[157]

その主唱者はギュスターヴ・クールベでした。彼は情熱的で政治的な気質を持ち、「ロマン主義者や古典主義者の誤り」を克服しようと決意した芸術家でした。クールベの作品は、裸体におけるリアリズムの導入を意味しました。それ以前の時代にも、多かれ少なかれ自然主義的なアプローチはありましたが、それらは概して人体の理想化概念に従属していました。クールベは、理想化も文脈化も図像的テーマで囲むこともせず、自然から捉えた形態をそのまま転写し、自らが知覚した通りの人体を描いた最初の人物でした。彼のモデルは概して、《水浴者》 (1853年) 《画家のアトリエ》(1855年)のモデル《横たわる裸婦》(1862年) 《オウムを連れた女》 (1865年) 《ロトと娘たち》 ( 1844年)《二人の水浴者》(1858年)《春》(1867年)のように、がっしりとした体格をしていました。彼は時に他の芸術家からインスピレーションを得ており、例えばアングルの有名な作品の複製である『泉』(1868年)や、フラゴナールの『二人の女友達』を想起させる『眠り姫たち』(1866年)などがその例である。彼の最も有名な作品の一つは『世界の起源』(1866年)で、頭部のない女性の身体を前面に出し、恥骨を前面に出すという、当時の人々を驚かせ、憤慨させた、極めて斬新なヴィジョンを描いている。[158]

もう一人の代表的人物はカミーユ・コローで、彼は主に風景画を描いていたが、時折風景画に人物像を描き加え、その中には裸婦像も含まれていた。その風景画は、アルカディア風の、蒸気のような雰囲気と繊細な色調を帯びた作品で、例えば『横たわるニンフ』(1855年)や『海辺のニンフ』(1860年)に見られる。後に彼は風景画と人物像を切り離し、1865年から1875年にかけて、女性像の研究に焦点を当てた作品を多数制作した。例えば『中断された読書』(1865年–1870年)や『真珠を持つ女』(1869年)などである。その他の作品としては、『ローマのオダリスク、マリエッタ』(1843年)、『ピンクのスカートの少女』(1853年–1865年)、『ディアナの浴室』(1855年)、『ニンフの踊り』(1857年)などがある。[159]

彫刻におけるリアリズムに相当するのはコンスタンタン・ムニエで、彼は古典的な英雄を現代のプロレタリアに置き換え、新しい産業時代の労働者や労働者を好んで描き、人物の立体感に特別な関連性を持たせた作品、例えば『水たまりの人』(1885年)やブリュッセルの労働記念碑( 1890-1905年)の『老人』などである。[160]もう一人の著名な彫刻家はカルポーの弟子であるエメ=ジュール・ダルーで、彼は自然主義であるにもかかわらず、 『バッカス祭』(1891年)、『足を乾かす水浴者』 (1895年) 、 『シレノスの勝利』 (1898年)などの作品で一定のバロックの影響を示している。

ヨーロッパに定住したアメリカ人、ジョン・シンガー・サージェントは、当時最も成功した肖像画家であり、風景画の才能に恵まれた画家、そして多くのアカデミーを去った偉大なデッサン家でもありました。ベラスケス、フランス・ハルス、アントニー・ヴァン・ダイク、そしてトーマス・ゲインズバラの影響を受け、優雅で高潔な作風を特徴としており、その作風は『浜辺の裸体少年』(1878年)や『ニコラ・ディンヴェルノ』(1892年)といった裸体画にも表れています。

スペインでも、19世紀半ばにはリアリズムが主流でした。エドゥアルド・ロサレスは多くのジャンルを手がけ、裸婦像は少ないものの(『眠る女』1862年、『水浴の後』1869年)、その質の高さは高く評価されるべきです。ライムンド・マドラソについても、デザインと構成のセンスが素晴らしい『水浴の後』(1895年)が特筆に値します。ナザレ主義の教育を受けたマリアノ・フォルトゥニは、東洋のテーマを扱った作品(『オダリスク』1861年)のほか、風俗画や風景を背景にした裸婦像(『牧歌』 1868年、『モデルの選択』 1870~1874年、『太陽の下の裸の老人』 1871年、『カルメン・バスティアン』 1871~1872年、『ポルティチの浜辺の裸婦』1874年)を数多く制作しました。他のアーティストとしては、カスト プラセンシア(『サビニ族の女性の強姦』、1874 年)、ホセ ヒメネス アランダ( 『売りに出される奴隷』、1897 年)、エンリケ シモネ( 『心臓の解剖学』、1890 年、『パリの審判』、1904 年)、そして彫刻家としてリカルド ベルベール( 『エル アンヘル カイド』、 1877年)。[161]

-

コンスタンタン・ムニエ作「労働記念碑」(1890-1905年)の「老人」(ブリュッセル)。

-

ニコラ・ディンベルノの肖像(1892 年)、ジョン・シンガー・サージェント作。

-

Leafless Flowers (es) (1894)、ラモン・カサス作

印象派

印象派は、アカデミックな芸術との決別と芸術言語の変革を象徴する、極めて革新的な運動であり、前衛芸術への道を拓きました。印象派の画家たちは自然からインスピレーションを得て、そこから視覚的な「印象」を捉えようとしました。写真の影響を受けた彼らは、キャンバス上の一瞬の瞬間を、自由な筆致と明るく鮮やかな色調、特に光を重視する技法を用いて捉えました。[162]

印象派の作品は古典的な伝統を大きく打ち破り、あらゆる慣習や古典的あるいは学問的な規制から離れて、自然の中にインスピレーションを求める新しい絵画様式を生み出した。例えば、エドゥアール・マネの『草上の昼食』(1863年)は、ラファエロの古典的な輪郭に明らかに影響を受けていたにもかかわらず、当時は完全なスキャンダルとなった。もっとも、論争は裸体画そのものではなく、不当な裸体画、匿名の現代女性であったことから生じたのだが。[163]マネが推し進めたもう一つの革命は『オランピア』(1863年)で、カラヴァッジョ風の雰囲気が繊細な気取りの様相を呈していたが、その写実的な外観が当時スキャンダルを引き起こし、作者はパリを去らざるを得なくなった。オリンピアは生身の女性であり、娼婦を体現しているがゆえに、恥知らずなまでにリアルである。そして、彼女は牧歌的な森や絵のように美しい遺跡ではなく、現実の舞台に立っている。これは親密な情景であり、鑑賞者に人間の最もプライベートな側面、すなわち親密さを見せる。一方で、モデルの具体的で個性的な特徴は、古典的な裸婦像の理想化された顔とはかけ離れた、彼女自身のアイデンティティを与えている。[164]

マネが始めた道を他の作家たちも引き継いだ。例えばエドガー・ドガ は、初期のアングル派に影響を受けた裸婦画の後、デッサンのデザインを基にした独自のスタイルへと進化し、本質的には生き生きとした自発性に満ちた場面での動きの転写にこだわった。ドガは、従来の美の規範から自発的に離れ、「若きスパルタ人」(1860年)やダンサーの描写に見られるように、未発達で思春期の体型を選んだ。一方、彼の作品は、写真や日本の 版画の影響を受け、ある種の盗み見的な要素を伴う、自発的に捉えた瞬間を捉えたスナップショットという顕著な特徴を持つ(「入浴中の女性」、1880年、「入浴後」、1883年、「足を乾かす女性」、1886年、「トイレ」、1886年、「入浴後、首を乾かす女性」、1895年)。[165]ドガはヌードの中に、トイレ(トイレット)というサブジャンルを開拓しました。トイレットとは、浴室で女性が個人的な衛生行為を行う様子を描いたもので、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて大きく発展しました。 1886年に開催された印象派最後の展覧会で発表された、入浴、手洗い、体を拭く、髪を梳かす、あるいは梳かされるといった女性たちを描いたヌード連作において、彼はヌードの新たなビジョンを提示しようと試みました。正面からではなく、横や後ろから描くことで、一瞬の出来事として捉えられた効果を強調し、女性が公衆の前に姿を現しているようには見えないようにしました。彼自身の言葉によれば、「これまでヌードは観客を前提としたポーズで表現されてきた。しかし、私の描く女性は素朴で誠実な人々であり、身だしなみに気を配るだけである。もう一つ、彼女は足を洗っている。まるで鍵穴から彼女を見ているかのようだ」とのことです。[166]

しかし、女性の身体を最もよく表現した一人はルノワールであり、彼は女性の身体を写実的に表現しながらも、ある種の崇拝を込め、理想的な完璧さを漂わせていた。「グリフォンの浴衣」 (1870年)では、クニドスのアフロディーテの版画にインスピレーションを受け、構図のコンセプトはクールベから受け継いでいる。ルノワールは、明るく感情を掻き立てる環境の中で、裸体の穏やかで落ち着いたイメージ、自然との一体化という理想を表現し、標準的な古典主義的姿勢と自然の現実感を融合させようとした。彼は、印象派の技法に倣い、光と影の斑点で空間をまだらにすることで人物の輪郭を薄くしようと努めた。これは、「アンナ」(1876年)や「トルソ」(1876年)に見られるように、色彩を通してフォルムを捉えるヴェネツィア派に影響を受けたものだった。後に、裸婦像を簡素化しようと試みる中で、ラファエロのフレスコ画「ラ・ファルネジーナ」やポンペイ、ヘルクラネウムの絵画に触発され、その影響は「 金髪の浴女」(1882年)に顕著に表れている。 「大浴女たち」(1885-1887年)では、ジラルドンの「ニンフの噴水」(ヴェルサイユ宮殿)に着想を得た、流麗な線と豊かな立体感を持つ彫刻的な裸婦像を描いた。晩年の作品では、アレクサンドリア・ヘレニズム、ミケランジェレスク・マニエリスム、ブーシェやクロディオンのバロック様式の影響を受けており、ふくよかで豊満な容姿の人物像と、身体や周囲の環境(一般的には川、湖、森、海岸)に対する自然な態度が描かれている(『座る水浴女』1885年、『体を乾かす水浴女』 1895年、『パリスの審判』 1908-1910年、『水浴者』1916年)。[167]

印象派の後継者は新印象派であり、これは点描技法、すなわち色の点による絵画の精緻化を根本とする様式である。その代表的人物の一人がジョルジュ・スーラで、彼は生涯を通じて海景、田園風景、サーカス、ミュージックホール、裸婦など、様々なテーマを好んで描いた。この分野における彼の代表作は『模型』(1886-1888年)である。スーラは、点描技法は風景画しか描けないとしばしば非難されていたため、この作品で点描技法があらゆるジャンルに応用可能であることを証明しようとした。この作品でスーラは、自身のアトリエにあるデッサンモデルを用いて、三美神のよく知られたテーマを現代的な解釈で再解釈した。そのヴィジョンは、ある意味でアングルの作品に影響を受けていた。[168]

その後、いわゆるポスト印象派は、印象派による新しい技術的発見から出発して、それを個人的な方法で再解釈し、20世紀の芸術の発展にとって非常に重要なさまざまな発展の道を切り開いた一連の芸術家たちでした。したがって、ポスト印象派は特定のスタイル以上に、異なるサインの多様な芸術家をグループ化する方法でした。ポール・セザンヌは、キュビズムの先駆けとなる現実の分析的統合において、幾何学的形状(円柱、円錐、球)で構成を構築しました。彼は、パリのプティ・パレにある彼の「水浴者」(1879-1882年)に見られるように、光に浸された色彩の量の関係の表現として、裸婦を風景画または静物画として扱いました。ポール・ゴーギャンは、象徴的な特徴を持つ平坦な色彩を用いて奥行きの実験を行い、絵画の平面に新しい価値をもたらしました。点描画法(『裸婦の習作』 、1880年)に着手し、ナビ派と共にポンタヴァンに滞在した経験(『黄色いキリスト』 、1889年)を経て、タヒチ滞在をきっかけに、裸婦が自然に観想される原始的な平穏な世界を再現するに至った。その作品は、『I Raro te Oviri』(1891年)、『Loss of Innocence』(1891年)、『Tahitian Eve』(1892年)、『Two Tahitian Women on the Beach』(1892年)、『Woman at Sea』(1892年)、『Manao tupapau』(1892年)、『The Moon and the Earth』(1893年)、『Otahí or Solitude』(1893年)、『Delicious Day』(1896年)、『The Mango Woman』(1896年)、『Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?(1897年)、『ヴァイルマティ』(1897年)、『ネバーモア』(1897年)、『そして彼女たちの肉体の黄金』(1901年)など。アンリ・ド・トゥールーズ=ロートレックは、アカデミックなサロンの様式化された裸婦画とは対照的に、サーカスやミュージックホール、ボヘミアンや売春宿の環境を好み、女性の姿を最も粗野な肉欲のままに研究し、肉体自身の欠陥を無視しませんでした。例えば、『太ったマリー』(1884年)、『ストッキングを上げる女』(1894年)、『検診』(1894年)、『二人の友人』(1894~1895年)、『ラ・トワレット』(1896年)、『シャツを持ち上げる女』(1901年)など。フィンセント・ファン・ゴッホ彼は力強いドラマと内面の探求を描いた作品を制作した。その筆致は、しなやかで濃密な筆致と強烈な色彩で、現実を歪め、夢のような雰囲気を醸し出していた。裸婦像もいくつか制作しており、そのほとんどは1887年にパリで制作された。横たわる裸婦像、ベッドの上の裸婦像、後ろ姿の裸婦像などである。[169]

彫刻の分野において、オーギュスト・ロダンは偉大な革新者でした。彼は物理的な面だけでなく、テーマの革新においても、神話や宗教とはかけ離れた、当時の環境における普通の人間に焦点を当てていました。彼は人体に関する深い知識を持ち、心理的な内省を強く意識しながら、親密な方法で人体を扱いました。ミケランジェロやドラクロワの影響も受けていましたが、彼の作品の本質は革新的で、裸体というテーマに新たな類型をもたらしました。そのために、彼はモデルをアトリエで自由に歩き回らせ、あらゆる形態をとらせました。ロダンは、あらゆる瞬間、あらゆる姿勢の自発性を巧みに捉え、不滅のものにしました。彼の人物像は、ドラマチックで、悲劇的な緊張感に満ち、運命に抗う人間という芸術家のコンセプトを表現しています。こうして彼は、30 年以上もの間、パリの装飾美術館(現在はロダン美術館が所蔵)の未完成プロジェクトである「地獄の門」(1880 年 - 1917 年)の人物像の制作に取り組んでいました。このプロジェクトからは、カルポーの「ウゴリーノ」にインスピレーションを得た「考える人」(1880 年 - 1900 年)や、 「神曲」で語られるパオロとフランチェスカの愛を表現した「接吻」(1886 年 - 1890 年)など、独立した人物像として切り離された作品がいくつかありました。その他の作品には『青銅時代』(1877年)、『洗礼者ヨハネ』(1878年)、『イヴ』(1881年)、『冬』(または『美しい女』 ( 1884年 - 1885年)、 『殉教者』(1885年)、『トルソ』(1889年)、『ミューズ』 (1896年)、 『三つの影』(1899年)、『ダナイド』(1901年)などがある。ロダンの後を継いだ彫刻家には、アントワーヌ・ブールデル(『射手ヘラクレス』(1909年)、カミーユ・クローデル(『懇願者』 (1894年 - 1905年)、 『成熟時代』(1899年 - 1913年)、ジョゼフ・ベルナール(『大釜を持つ女』(1910年) 、シャルル・デスピオー(『イヴ』 1925年)などがいる。[170]

スウェーデン人のアンデシュ・ゾルンは、主に風景画に、大胆に官能的で健康的なヌードを描きました。肌に鮮やかな光の効果を施し、鮮やかな色彩の筆致で描いた作品で、例えば『 野外にて』(1888年)、『水浴者たち』(1888年)、『サウナで水浴する女たち』(1906年)、『日光浴する少女』(1913年)、『ヘルガ』(1917年)、『スタジオ牧歌』(1918年)などが挙げられます。[171]

スペインでは、ホアキン・ソローリャの作品が際立っていました。彼は、自由な技法と力強い筆遣い、明るく繊細な色彩で印象派を独自の方法で解釈し、光が特に重要で、子供たちが遊び、社交界の貴婦人が散歩し、漁師が仕事に従事するビーチや海の景色など、地中海をテーマにした彼のシーンを囲む明るい雰囲気が特徴です。彼の作品には、「悲しい相続」(1899 年)、「死の女神」(1902 年)、「馬の風呂」(1909 年)、「浜辺の子供たち」(1910 年)、 「風呂のあと」 (1911 年)などのいくつかのヌードが含まれています。彼の弟子には、義理の息子フランシスコ・ポンス・アルナウ(作曲家)、イグナシオ・ピナソ(デスヌード・デ・フレンテ)がいます。 、1872–1879)、リゴベルト・ソレル(ニネタ、デプス・デル・バーニョ)、フリオ・モイセス(エヴァ、ピリ)。[172]

-

横たわる女性の裸体(1887 年)、フィンセント・ファン・ゴッホ作、S. ヴァン・デーヴェンター、デ・ステーグコレクション。

-

Desnudo de mujer (1902)、ホアキン・ソローリャ作、マドリードのソローリャ美術館。

象徴主義

象徴主義は幻想的で夢想的な様式であり、写実主義や印象派の自然主義への反動として現れ、夢の世界、悪魔的・恐怖的側面、性、倒錯に特に重点を置いた。象徴主義の主要な特徴は、当時支配的だった功利主義と産業時代の醜悪さと物質主義への反動である、美学主義であった。これに対し、芸術と美に独自の自律性を与える傾向が生まれ、テオフィル・ゴーティエの「芸術のための芸術」という定式に統合され、「美的宗教」とさえ呼ばれるようになった。この立場は、芸術家を社会から孤立させ、自らのインスピレーションを自律的に求め、個人的な美の探求のみに突き動かされることを目指した。[173]

象徴主義の特徴の一つは、倒錯した女性、ファム・ファタール、イヴがリリスに変貌したような、謎めいてよそよそしく、不安を掻き立てる女性への暗い魅力である。マヌエル・マチャドは彼女を「脆く、邪悪で神秘的な、ラファエル前派の処女にしてパリの猫」と形容した。彼女は愛され、憎まれ、崇拝され、中傷され、称賛され、拒絶され、高潔で、罪深い女性であり、スフィンクス、人魚、キメラ、メデューサ、翼のある精霊など、様々な象徴的・寓意的な形態をとることになる。人工的で両性具有的で、曖昧なタイプの美、レオナルド風の美が流行し、その特徴は不明瞭であり、ユリなどの花や、白鳥や孔雀などの動物に象徴的に等価物を持つことになる。[174]

象徴主義は特にフランスで発展しましたが、その創始者の一人であるロマン主義の継承者である芸術家ギュスターヴ・モローは、イタリアの40世紀を代表する巨匠たちに深い尊敬の念を抱いていました。彼の作品は幻想的で装飾的なスタイルで、あらゆる種類の物体や植物の要素が密集した多彩な構成と、彼の恐怖と執着を反映した示唆的なエロティシズム、無邪気さと倒錯の間の曖昧な女性の原型を持っている。次のような作品がある:『オイディプスとスフィンクス』(1864年)、『オルフェウス』(1865年)、『イアソン と メディア』( 1865年)、『レダ』(1865年 - 1875年)、 『キマイラ』 ( 1867年)、 『プロメテウス』(1868年)、『エウロペの略奪』 ( 1869年)、『セイレーン』 (1872年)、 『亡霊』(1874年 - 1876年)、『サロメ』 (1876年)、『レルナのヘラクレスとヒュドラ』(1876年)、『ガラテイア』(1880年)、『ユピテルとセメレ』(1894年 - 1896年)。[175]

ピエール・ピュヴィス・ド・シャヴァンヌなどの芸術家が彼の後を継ぎ、印象派の実験の後に線描に戻り、メランコリックな風景画で裸体像を豊富に描いた大壁画を制作した。その例としては、『仕事』( 1863年)、『秋』(1865年)、『希望』(1872年)、『海辺の少女たち』 (1879年)、『聖なる森、芸術とミューズに愛された人々』(1884年 - 1889年)などがある。オディロン・ルドンは夢の中に尽きることのないインスピレーションの源を見出し、柔らかな描写と燐光のような色彩を基調とした作風で、強い夢想的要素を持つ作品を制作した(『キュクロプス』、1898年 - 1900年)。アリスティード・マイヨールは、自然界の女性の姿に大きな関心を抱き、絵画から始めた(『地中海』1898年、『波』 1898年、『風景の中の二人の裸婦』1900年)。後に彫刻に移り、そこで彼は最も適した表現手段を見つけた:『夜』(1902–1909年)、『地中海』(1902–1923年)、『連鎖行為』(1906年)、 『若い自転車乗り』 (1908年)、『水浴びの少女が乾く』(1921年)、『首飾りのヴィーナス』(1930年)、『三人のニンフ』(1930–1937年)、『山』(1937年)、『河』(1938–1943年)、『空気』(1939年)。[176]

ゴーギャンの影響を受け、色彩表現にこだわったナビ派と呼ばれる芸術家集団がポン=タヴァンで会合を持った。そのメンバーには、ブラックユーモアを含んだ皮肉な作風を展開したフェリックス・ヴァロットンや、露骨なエロティシズムを湛え、日本的な平坦な体型と仮面のような顔をしたフェリックス・ヴァロットン(『夏の午後の水浴』、1892年)などがいた。ピエール・ボナールは、自然光と人工光の両方を使って、寝室や閨房など親密な場面で裸婦を描き、鏡に映る絵を好み、写真を参考にすることが多かった(『ベッドに寄りかかる女性』、1899年、『昼寝』、1900年、『男と女』、1900年、『光に逆らう裸婦』、1907年、『鏡効果』、1909年、『鏡付き化粧台』、1913年、『バケツの中の裸婦』、1916年)。そして、チャールズ・フィリガーは、特にゴシックのステンドグラスから影響を受けた、平面的な色彩と黒い輪郭の中世風のスタイルを発展させました。その一例として、ホルバインの「墓の中のキリストの遺体」に触発された「横たわるキリスト」(1895年)が挙げられます。この作品は、単純で純粋な形にまで削ぎ落とされ、キリストを超越的で喚起的な人物、純粋さを暗示する素朴さに変えるような象徴的な率直さを示しています。[177]

ベルギーでは、フェリシアン・ロップスも幻想世界や超自然の世界からインスピレーションを受け、悪魔的な側面や死への言及、そして愛の暗く倒錯した側面を反映したエロティシズムを作品に表現しました。『冷たい悪魔たち』(1860年)、『聖アントニウスの誘惑』(1878年)、『ポルノクラテス』(1878年)、『犠牲』(1882年)などが挙げられます。ジャン・デルヴィルはオカルティズムに興味を持ち、作品の中で秘密の執着を表現し、肉体と精神が混ざり合った人物像を描きました。『倒錯の偶像』(1891年)、『悪魔の宝物』(1895年)、『プラトンの学校』(1898年)、『魂の愛』(1900年)などが挙げられます。彫刻では、ジョルジュ・ミンネが「ひざまずく若者たちのいる噴水」 (1898-1906)の作者である。この作品では、裸の若者の同じ姿が池の周りに5回繰り返され、まるでナルキッソスが水面に映る自分の姿を見つめているかのように、視線を内面へと導き、そこに映る苦悩の解決策を探している。[178]

オランダでは、ヤン・トーロップが傑出した作品を残しました。彼は『三人の花嫁』(1893年)を制作し、長い腕と繊細なシルエットを持つ人物像によって、生まれ故郷のジャワ島に漂う中国の影の影響を強く感じさせます。ピエト・モンドリアンは、新造形主義的 抽象表現に至る以前、秘教への関心から生まれた象徴主義的な作品を制作しました。『進化』(1910-1911年)は、完全に霊化された3人の裸体を描いた三連祭壇画で、知識と神秘的な光へのアクセスを象徴しています。[179]

イギリスでは、ラファエル前派という流派が生まれました。彼らは、その名前が示すように、ラファエロ以前のイタリアの画家たちや、当時登場した写真術からインスピレーションを得ました。彼らの主題は叙情的で宗教的なものを好んでいたが、ダンテ・ゲイブリエル・ロセッティ(『めくるヴィーナス』、1868年)、エドワード・バーン=ジョーンズ(『ピグマリオン』シリーズ、1868年~1870年、 『パンの園』、1876年、『運命の輪』、1883年、 『三美神』、1890年)、ジョン・エヴァレット・ミレー(『遍歴の騎士』 、1870年)、ジョン・ウィリアム・ウォーターハウス(『ヒュラスとニンフ』、1896年)などが裸婦像にも取り組んだ。ラファエル前派の象徴主義と近代主義の装飾主義の間には、イラストレーターのオーブリー・ビアズリーの作品があり、彼はエロティックな性質の作品を数多く制作した( 『リシストラタ』やオスカー・ワイルドの『サロメ』の挿絵など)。そのスタイルは、高度に様式化された線と大きな黒い線をベースとしており、大きな風刺と不遜な感覚で描かれている。そして白い表面。[180]

The German Franz von Stuck developed a decorative style close to modernism, although its subject matter is more symbolist, with an eroticism of torrid sensuality that reflects a concept of woman as the personification of perversity: Sin (1893), The Kiss of the Sphinx (1895), Air, Water, Fire (1913). In Austria, Gustav Klimt recreated a fantasy world with a strong erotic component, with a classicist composition of ornamental style, where sex and death are intertwined, dealing without taboos with sexuality in aspects such as pregnancy, lesbianism or masturbation. In Nuda Veritas (1899) he moved away from the iconographic symbolism of the female nude, becoming a self-referential symbol, the woman is no longer an allegory, but an image of herself and her sexuality. Other works of his are: Agitated Water (1898), Judith I (1901), the Beethoven Frieze (1902), Hope I (1903), The Three Ages of Woman (1905), Danae (1907), Judith II (Salome) (1909), The Girlfriends (1917), Adam and Eve (1917–1918), etc.[181] Alfred Kubin was above all a draftsman, expressing in his drawings a terrifying world of loneliness and despair, populated by monsters, skeletons, insects and hideous animals, with explicit references to sex, where the female presence plays an evil and disturbing role, as evidenced in works such as Lubricity (1901–1902), where a priapic dog harasses a young woman huddled in a corner; or Somersault (1901–1902), where a small homunculus jumps as if in a swimming pool over a huge female vulva.[182]

_-_Ferdinand_Hodler_(Kunstmuseum_Bern).jpg/440px-Der_Tag_(1899-1900)_-_Ferdinand_Hodler_(Kunstmuseum_Bern).jpg)

In Switzerland, Ferdinand Hodler was influenced by Dürer, Holbein and Raphael, with a style based on parallelism, repeating lines, colors and volumes: Night (1890), Rise in Space (1892), Day (1900), Sensation (1901–1902), Young Man Admired by Women (1903), Truth (1903). Arnold Böcklin was heir to Friedrich's romanticism, with an allegorical style based on legends and imaginary characters, recreated in a fantastic and obsessive atmosphere, as in Venus Genitrix (1895). The Czech František Kupka was also interested in occultism, going through a symbolist phase before reaching abstraction: Money (1899), Ballad of Epona (The Joys) (1900), The Wave (1902). In Russia, Kazimir Malevich, future founder of suprematism, had in its beginnings a symbolist phase, characterized by eroticism combined with a certain esoteric mysticism, with a style tending to monochrome, with a predominance of red and yellow: Woman picking flowers (1908), Oak and Dryads (1908).[183]

Linked to symbolism was also the so-called naïf art, whose authors were self-taught, with a somewhat naive and unstructured composition, instinctive, with a certain primitivism, although fully conscious and expressive. Its greatest exponent was Henri Rousseau, who, starting from academicism, developed an innovative work, of great freshness and simplicity, with humorous and fantastic touches, and a predilection for the exotic, jungle landscape. He made some nudes, such as The Snake Charmer (1907), Eve (1907) and The Dream (1910).[184]

-

The Temptations of Saint Anthony (1878), by Félicien Rops, Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

-

Sin (1893), by Franz von Stuck, Neue Pinakothek, Munich.

-

Agitated Water (1898), by Gustav Klimt, Private Collection, New York City.

-

The Knight's Dream (1902), by Richard Mauch, private collection.

-

Nudes (1919), by Suzanne Valadon, São Paulo Museum of Art.

20th century

_by_Florine_Stettheimer,_c_1915-16.jpg/440px-A_Model_(Nude_Self-Portrait)_by_Florine_Stettheimer,_c_1915-16.jpg)

The art of the 20th century underwent a profound transformation: in a more materialistic, more consumerist society, art addresses the senses, not the intellect. Likewise, the concept of fashion has gained special relevance, a combination of the speed of communications and the consumerist aspect of today's civilization. Thus the avant-garde movements arose, which sought to integrate art into society, seeking a greater artist-spectator interrelationship, since it is the latter who interprets the work, being able to discover meanings that the artist did not even know. The latest artistic trends have even lost interest in the artistic object: traditional art was an art of the object, the current art of the concept. There is a revaluation of active art, of action, of spontaneous, ephemeral manifestations, of non-commercial art (conceptual art, happening, environment).[185]

In the twentieth century the nude has been gaining more and more prominence, especially thanks to the mass media, which have allowed its wider dissemination, especially in film, photography and comics, and more recently, the Internet. It has also proliferated to a great extent in advertising, due to its increasing social acceptance, and being a great attraction for people. Nudity no longer has the negative connotation it had in previous times, mainly due to the increase of secularism among society, which perceives nudity as something more natural and not morally objectionable. In this sense, nudism and naturism have been gaining followers in recent years, and no one is scandalized to see another person naked on a beach. It is also worth noting the growing cult of the body, with practices such as bodybuilding, fitness and aerobics, which allow the body to be shaped according to standards that are considered aesthetically pleasing.

Vanguardism