L. L. Zamenhof

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards.(January 2026) |

L. L. Zamenhof | |

|---|---|

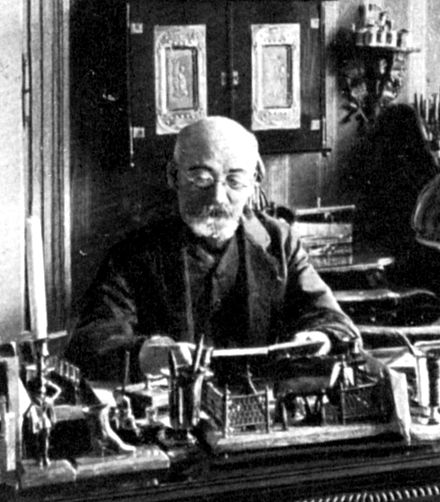

Zamenhof, c. 1895 | |

| Born | Leyzer Zamengov[a] (1859-12-15)15 December 1859[b]Belostok, Russian Empire |

| Died | (1917-04-14)14 April 1917[b] (aged 57) Warsaw, Poland |

| Burial place | Jewish Cemetery, Warsaw52°14′43″N20°58′34″E / 52.24528°N 20.97611°E / 52.24528; 20.97611 |

| Occupation | Ophthalmologist |

| Known for | Esperanto |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Awards | Legion of Honour (Officer, 1905) |

| Writing career | |

| Pen name | Dr. Esperanto |

| Notable works |

|

| Signature | |

| |

L. L. Zamenhof[a] (15 December 1859 – 14 April 1917)[b] was the creator of Esperanto, the most widely used constructedinternational auxiliary language.[1][2]

Zamenhof published Esperanto in 1887, although his initial ideas date back as far as 1873. He grew up fascinated by the idea of a world without war and believed that this could happen with the help of a new international auxiliary language (IAL).[3] The language was intended as a tool to gather people together through neutral, fair, equitable communication.[4] He successfully formed a community which has survived to this day, despite the World Wars of the 20th century[5] and various attempts to reform the language or create more modern IALs (Esperanto itself had displaced another similarly-motivated language, Volapük). Additionally, Esperanto has developed like other languages: through the interaction and creativity of its users.[6]

In light of his achievements, and his support of intercultural dialogue, UNESCO selected Zamenhof as one of its eminent personalities of 2017, on the 100th anniversary of his death.[7][8] According to Esperanto communities, as of 2019 there are approximately 2 million people speaking Esperanto, including approximately 1,000 native speakers,[9][10] although evidence to that has been heavily disputed,[11] and the last major effort to improve the estimate occurred in 2004.[9]

Name

Zamenhof came from a multilingual area. His name is transliterated as follows:

- English: Louis Lazarus Zamenhof – English pronunciation:/ˈzæmənhɒf,ˈzæmɪnhɒf,-nɒv,-nɒf/

- Esperanto: Ludoviko Lazaro Zamenhof – pronounced[ludoˈvikolaˈzarozamenˈhof]

- French: Louis Lazare Zamenhof – pronounced[lwila.zaʁza.mɛn.of]

- German: Ludwig (Levi) Lazarus Zamenhof – pronounced[ˈluːtvɪçˈlaːtsaʁʊsˈt͡saːmənhoːf]

- Hebrew: אליעזר (לודוויג) זמנהוף, romanized: Eli'ezer Ludvig Zamenhof – pronounced[eliˈ(ʕ)ezeʁˈludvigˈzamenhof]

- Lithuanian: Liudvikas Lazaris (Leizeris) Zamenhofas

- Polish: Ludwik Łazarz Zamenhof – pronounced[ˈludvʲikˈwazaʐzaˈmɛnxɔf]

- Russian: Людвик Лазарь (Лейзер) Маркович Заменгоф, romanized: Lyudvik Lazar' (Leyzer) Markovich Zamengof

- Belarusian: Людвіг Лазар Маркавіч Заменгоф (Заменгоў), romanized: Liudvih Lazar Markavič Zamienhof (Zamienhoŭ)

- Yiddish: לײזער לוי זאַמענהאָף, romanized: Leyzer Leyvi Zamenhof

Born into an Ashkenazi family, at his birth Zamenhof was given the common Hebrew name Eliezer by his parents, which is translated into English as Lazarus. However, as the area was a part of the Russian Empire at the time, his name was recorded on his birth certificate as Лейзер Заменгов, Leyzer Zamengov, using the Yiddish form of the forename and a russified version of his surname;[12] many later Russian language documents also include the patronymicМаркович, Markovich « son of Mark » (in reference to his father, Markus), as is the custom in the language. His family name is of German origin and was originally written Samenhof; this was later transcribed into Yiddish as זאַמענהאָף, then re-romanized back as Zamenhof. The change of the initial letter from «S» to «Z» is not unusual, as in German an initial «s» is pronounced [z].

In his adolescence, he used both the Yiddish Leyzer and the Russian Lazar when writing his first name. While at university, Zamenhof began using the Russian name Lyudovik (also transcribed Ludovic or translated as Ludwig) in place of Lazar, possibly in honour of Francis Lodwick, who in 1652 had published an early conlang proposal.[13] When his brother Leon became a doctor and started signing his name "Dr L. Zamenhof",[14] Zamenhof reclaimed his birth name Lazar and from 1901 signed his name "Dr L. L. Zamenhof" to avoid confusion with his brother. The two Ls do not seem to have specifically represented either name and the order Ludwik Lejzer is a modern convention.

Early years

Zamenhof was born on 15 December 1859,[b] the son of Mark and Rozalia Zamenhof (née Sofer), in the multi-ethnic city of Belostok in the Russian Empire[15] (now Białystok in Poland).[16][17][18] He went to a cheder until age 13, and later to secondary school in Warsaw. He developed an interest in poetry and drama, and wrote several pieces, including a five act play about the Tower of Babel.[19]

He appears to have been natively bilingual in Yiddish and Russian, however according to Zamenhof himself he used to speak mainly in Polish.[18] His father was a teacher of French and German. From him, Zamenhof learned both languages, as well as Hebrew. He also spoke Belarusian, which was popular in Białystok. Polish became the native language of his children in Warsaw. In school, he studied the classical languages Latin, Greek, and Aramaic. He later learned some English, though in his own words not very well. He had an interest in Italian and Lithuanian and learned Volapük when it came out in 1880. By that time, his international language project was already well-developed.[20][21]

In addition to the Jewish Yiddish-speaking minority, the population of Białystok included Polish Catholics and the Russian Orthodox (the latter of whom were mainly government officials), with smaller groups of Belarusians, Germans and other ethnicities. Zamenhof was saddened and frustrated by the many quarrels among these groups. He supposed that the main reason for the hate and prejudice lay in the mutual misunderstanding caused by the lack of a common language. If such a language existed, Zamenhof postulated, it could play the role of a neutral communication tool between people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds.[22][23]

| Part of a series on |

|

|---|

As a student at secondary school in Warsaw, Zamenhof attempted to create an international language with a grammar that was rich, but complex. When he later studied English, he decided that the international language must have simpler grammar. Apart from his parents' native languages Russian and Yiddish and his adopted language Polish, his projects were also aided by his mastery of German, a good passive understanding of Latin, Hebrew and French, and a basic knowledge of Greek, English and Italian.[24]

His project, Lingwe uniwersala, was finished by 1878.[25] He went to Moscow the next year to study medicine. While there, he experienced the rise of antisemitism in the Russian Empire at the time, and became involved with Zionism. He returned to Warsaw to finish his studies and began an ophthalmology residency in 1885.[19] He began his practice as a doctor in Veisiejai. After 1886, he worked as an ophthalmologist in Płock and Vienna. While healing people there, he continued to work on his project of an international language.[26]

He moved to Grodno and became involved in Zionism again, and later began to develop a new religion, Hillelism, later called Homaranism.[19] For two years, he tried to raise funds to publish a booklet describing the language, until he received financial help from his future wife's father. In 1887, the book titled Международный язык. Предисловие и полный учебникъ (International language: Introduction and complete textbook) was published in Russian[27] under the pseudonym "Doktoro Esperanto" (Doctor Hoper, or literally "Doctor One Who Hopes"). Zamenhof initially called his language "Lingvo internacia" (international language), but those who learned it began to call it Esperanto after his pseudonym, and this soon became the official name for the language. For Zamenhof, this language, far from being merely a communication tool, was a way to promote peaceful coexistence between people of different cultures.[2]

Homaranismo

Besides his linguistic work, Zamenhof published a religious philosophy he called Homaranismo (the term in Esperanto, usually rendered as "humanitism" in English,[28] sometimes rendered loosely as humanitarianism or humanism), based on the principles and teachings of Hillel the Elder. He said of Homaranismo: "It is indeed the object of my whole life. I would give up everything for it."[29]

Yiddish language and Jewish issues

In 1879, Zamenhof wrote the first grammar of Yiddish. It was partly published years later in the Yiddish magazine Lebn un visnshaft.[30] The complete original Russian text of this manuscript was only published in 1982, with parallel Esperanto translation by Adolf Holzhaus, in L. Zamenhof, provo de gramatiko de novjuda lingvo (An attempt at a grammar of neo-Jewish language), Helsinki, pp. 9–36. In this work, not only does he provide a review of Yiddish grammar, but also proposes its transition to the Latin script and other orthographic innovations. In the same period, Zamenhof wrote some other works in Yiddish, including perhaps the first survey of Yiddish poetics (see p. 50 in the above-cited book).

A wave of pogroms within the Russian Empire in 1882, including Congress Poland, motivated Zamenhof to take part in the Hibbat Zion, and to found a Zionist student society in Warsaw.[31] He left the movement following the publication of Unua Libro in 1887, and in 1901 published a statement in Russian with the title Hillelism, in which he argued that the Zionist project would fail due to Jews not having a common language.[31]

In 1914, he declined an invitation to join a new organization of Jewish Esperantists, the TEHA. In his letter to the organizers, he said, "I am profoundly convinced that every nationalism offers humanity only the greatest unhappiness ... It is true that the nationalism of oppressed peoples – as a natural self-defensive reaction – is much more excusable than the nationalism of peoples who oppress; but, if the nationalism of the strong is ignoble, the nationalism of the weak is imprudent; both give birth to and support each other".[31] The Hebrew Bible is among the many works that Zamenhof translated into Esperanto.

Death

Zamenhof died in Warsaw on 14 April 1917,[b] possibly of a heart attack,[32] and was buried at the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery. The farewell speech was delivered by the chief rabbi and preacher of the Great Synagogue in Warsaw, Samuel Abraham Poznański, who said: "There will be a time where [sic] the Polish soil and nation will understand what fame gave this great son of God to his homeland."[33]

Family

Zamenhof and his wife Klara Silbernik raised three children, a son, Adam, and two daughters, Zofia and Lidia. Lidia, in particular, took a keen interest in Esperanto, and as an adult became a teacher of the language, travelling through Europe and to America to teach classes in it. Through her friendship with Martha Root, Lidia became a member of the Baháʼí Faith. As one of its social principles, the Baháʼí Faith teaches that an auxiliary world language should be selected by the representatives of all the world's nations. All three of Zamenhof's children were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.[34]

Zamenhof's grandson through Adam, Louis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof, lived in France from the 1960s until his death in 2019, and whose daughter, Margaret Zaleski-Zamenhof, is still active in the Esperanto movement.

Honours and namesakes

In 1905, Zamenhof received the Légion d'honneur for creating Esperanto.[35] In 1910, Zamenhof was first nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, by four British Members of Parliament (including James O'Grady and Philip Snowden) and Professor Stanley Lane Poole.[36] (The Prize was instead awarded to the International Peace Bureau.) Ultimately Zamenhof was nominated 12 times for the Nobel Peace Prize.[37] On the occasion of the fifth Universala Kongreso de Esperanto in Barcelona, Zamenhof was made a Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic by King Alfonso XIII of Spain.[38]

A monument or place linked to Zamenhof or Esperanto is known as a Zamenhof-Esperanto object (or ZEO).

The minor planet1462 Zamenhof is named in his honour. It was discovered on 6 February 1938 by Yrjö Väisälä. There is also a minor planet named in honour of Esperanto (1421 Esperanto).

Hundreds of city streets, parks, and bridges worldwide have also been named after Zamenhof. In Lithuania, the best-known Zamenhof Street is in Kaunas, where he lived and owned a house for some time. There are others in Poland, the United Kingdom, France, Hungary, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Spain (mostly in Catalonia), Italy, Israel, Belgium, the Netherlands and Brazil. There are Zamenhof Hills in Hungary and Brazil, and a Zamenhof Island in the Danube.[39]

In some Israeli cities, street signs identify Esperanto's creator and give his birth and death dates, but refer to him solely by his Jewish name Eliezer, his original birth name. Zamenhof is honoured as a deity by the Japanese religion Oomoto, which encourages the use of Esperanto among its followers. A genus of lichen has been named Zamenhofia in his honour,[40] as well as the species Heteroplacidium zamenhofianum.[41]

Russian writer Nikolaj Afrikanoviĉ Borovko , who lived in Odessa, together with Vladimir Gernet , founded a branch of the first official Esperanto society Esrero in Russia. In the years 1896–97 N. A. Borovko became its chairman. A monument to L. Zamenhof was installed in Odessa in an ordinary residential courtyard. Esperantist sculptor Nikolai Vasilyevich Blazhkov lived in this house, who in the early 1960s brought a sculptural portrait into the courtyard because the customs authorities did not allow the sculpture to be sent to the Esperanto Congress in Vienna.[42]

A public square in Gothenburg, Sweden is named Esperantoplatsen, where a café named Zamenhof opened in 2018.[43]

In Italy, a few streets are named after Esperanto, including Largo Esperanto in Pisa.[44]

In 1959, UNESCO honoured Zamenhof on the occasion of his centenary.[45] In 2015, it decided to support the celebration of the 100th anniversary of his death.[46]

His birthday, 15 December, is celebrated annually as Zamenhof Day by users of Esperanto. On 15 December 2009, Esperanto's green-starred flag flew on the Google homepage to commemorate Zamenhof's 150th birthday.[47]

The house of the Zamenhof family and a monument to Zamenhof are sites on the Jewish Heritage Trail in Białystok, which was opened in June 2008 by volunteers at The University of Białystok Foundation.[48] Białystok is also home to the Ludwik Zamenhof Centre.[49]

In 1960, Esperanto summer schools were established in Stoke-on-Trent in the United Kingdom by the Esperanto Association of Britain (EAB), which began to provide lessons and promote the language locally. There is a road named after Zamenhof in the city: Zamenhof Grove.[50]

As Zamenhof was born on 15 December 1859, the Esperanto Society of New York gathers every December to celebrate Zamenhofa Tago (Zamenhof Day in Esperanto).[51]

Partial bibliography

Original works

- Unua Libro, 1887 (First Book)

- Dua Libro, 1888 (Second Book)

- Hilelismo – propono pri solvo de la hebrea demandoArchived 20 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 1901 (Hillelism: A Project in Response to the Jewish Question)

- Esenco kaj estonteco de la ideo de lingvo internaciaArchived 13 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 1903 (Essence and Future of the Idea of an International Language)

- Fundamenta Krestomatio de la Lingvo EsperantoArchived 4 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 1903 (Basic Anthology of the Esperanto Language)

- Fundamento de Esperanto, 1905 (Foundation of Esperanto)

- Declaration of Boulogne, 1905

- HomaranismoArchived 5 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 1913 (Humanitism)

Periodicals

- La Esperantisto, 1889–1895 (The Esperantist)

- Lingvo Internacia, 1895–1914 (International Language)

- La Revuo, 1906–1914 (The Review)

Poems

- "Al la fratoj" ("To the Brothers")[52]

- "Ho, mia kor'" ("Oh, My Heart")

- "La Espero" ("The Hope")

- "La vojo" ("The Way")[53]

- "Mia penso" ("My Thought")[54]

Translations

- Hamleto, Reĝido de DanujoArchived 29 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 1894 (Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, by William Shakespeare)

- La batalo de l' vivoArchived 25 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine (The Battle of Life, by Charles Dickens)

- La revizoro, 1907 (The Government Inspector, by Nikolai Gogol)

- La Predikanto, 1907 (translation of Ecclesiastes)

- La Psalmaro, 1908 (translation of the book of Psalms)

- La rabistojArchived 22 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 1908 (The Robbers, by Friedrich Schiller)

- Ifigenio en TaŭridoArchived 29 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 1908 (Iphigenia in Tauris, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe)

- La Rabeno de Baĥaraĥ, 1909 ("The Rabbi of Bacharach", by Heinrich Heine)

- La Gimnazio, 1909 ("The High School", by Scholem Aleichem)

- MartaArchived 14 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 1910 (Marta, by Eliza Orzeszkowa)

- Genezo, 1911 (translation of the Book of Genesis)

- Eliro, 1912 (translation of the Book of Exodus)

- Levidoj, 1912 (translation of the Book of Leviticus)

- Nombroj, 1914 (translation of the Book of Numbers)

- Readmono, 1914 (translation of the Book of Deuteronomy)

- Malnova Testamento (parts of the Old Testament)

See also

Notes

References

- ^Korzhenkov, Aleksandr (2009). Zamenhof: The Life, Works, and Ideas of the Author of Esperanto(PDF). Translated by Ian M. Richmond. Washington, D.C.: Esperantic Studies Foundation. Archived(PDF) from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ abZasky, Jason (20 July 2009), "Discouraging Words", Failure Magazine, archived from the original on 23 January 2017, retrieved 31 December 2013,

But in terms of invented languages, it's the most outlandishly successful invented language ever. It has thousands of speakers—even native speakers—and that's a major accomplishment as compared to the 900 or so other languages that have no speakers. – Arika Okrent

- ^Gabriela Zalewska (2010). "Zamenhof, Ludwik (1859–1917)". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Trans. by Anna Grojec. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^Guilherme Moreira Fians, Hoping for the language of HopeArchived 14 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, University of Amsterdam, ACLC Seminar, Amsterdam Institute for Humanities Research (AIHR),

- ^Gobbo, Federico (8 October 2015). "An alternative globalisation: why learn Esperanto today?". University of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^Humphrey Tonkin, Fourth Interlinguistic Symposium, p. 213, JKI-12-2017[1] (pdf).

- ^Fourth Interlinguistic Symposium, p. 209, permanent dead link]#x5D;.pdf JKI-12-2017[1].

- ^"Anniversaries 2017". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ ab"Esperanto". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^Babbel.com; GmbH, Lesson Nine. "What Is Esperanto, And Who Speaks It?". Babbel Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^Folio, Libera (13 February 2017). "Nova takso: 60.000 parolas Esperanton". Libera Folio (in Esperanto). Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^Birth Certificate N 47: "Leyzer Zamengov, son of Mordkha Fayvelovich Zamengov and Liba Sholemovna Sofer"Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Umberto Eco & James Fentress (9 September 1995). The Search for the Perfect Language. Blackwell Publishing. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-631-17465-3.

- ^Wincewicz, Andrzej; Sulkowska, Mariola; Musiatowicz, Marcin; Sulkowski, Stanislaw (June 2009). "Laryngologist Leon Zamenhof—brother of Dr. Esperanto". American Journal of Audiology. 18 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2008/08-0002). ISSN 1059-0889. PMID 18978199.

- ^Russell, James R. (8 February 2022). "Did Esperanto answer the 'Jewish Question'?". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022.

Leyzer (Eliezer) Levi Zamenhof was born in 1859 into a Jewish family in Belostok, a provincial city in the Russian Empire, now Bialystok, Poland.

- ^"100th anniversary of the death of L. ZAMENHOF, the creator of the Esperanto". Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^Korzhenkov, Aleksander (2010). Zamenhof: The Life, Works and Ideas of the Author of Esperanto. Mondial. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-59569-167-5. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

..born on December 15, 1859, into a Jewish family in what was then the Russian city of Bialystock...

- ^ abKiselman, Christer (2008). "Tom II". Esperanto: Its Origins and Early History(PDF). Prace Komisji Spraw Europejskich PAU: Polish Academy of Learning. pp. 39–56. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

What was his first language? He wrote in a letter in 1901 that his "parental language" (mother tongue) was Russian, but that at the time he was speaking more in Polish (Zamenhof 1929:523). However, all other evidence points to Yiddish as his mother tongue and first language. He was born in Białystok on December 3, 1859

- ^ abcZalewska, Gabriela. "Zamenhof, Ludwik". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Retrieved 16 January 2026.

- ^Christer Kiselman, "Esperanto: Its origins and early history"Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, in Andrzej Pelczar, ed., 2008, Prace Komisji Spraw Europejskich PAU, vol. II, pp. 39–56, Krakaw.

- ^Claude Piron (1984). "Kontribuaĵo al la studo pri la influoj de la jida sur Esperanton". Jewish Language Review. 4. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^"Birth of Ludwig Zamenhof, creator of Esperanto | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^Kellman, Steven G. (30 August 2016). "The Secret Jewish History of Esperanto". The Forward. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^Holzhaus, Adolf: Doktoro kaj lingvo Esperanto. Helsinki: Fondumo Esperanto. 1969

- ^Dufour, Fritz (2017). Exploring the Possibilities for the Emergence of a Single and Global Native Language. Fritz Dufour. p. 93.

- ^"Birth of Ludwig Zamenhof, creator of Esperanto". History Today. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^Keith Brown and Sarah Ogilvie, Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World (Elsevier, 2009: ISBN 0-08-087774-5), p. 375.

- ^Meaning in the Age of Modernism: C. K. Ogden and his contemporariesArchived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Thesis of James McElvenny, 2013

- ^Edmond Privat, The Life of Zamenhof, p. 117.

- ^Vilnius, 1909; see Esperanto translation as Pri jida gramatiko kaj reformo en la jida (On Yiddish grammar and reform in Yiddish) in Hebreo el la geto: De cionismo al hilelismo (A Hebrew from the ghetto: From Zionism to Hillelism), Eldonejo Ludovikito, vol. 5, 1976

- ^ abcN. Z. Maimon (May–June 1958). "La cionista periodo en la vivo de Zamenhof". Nica Literatura Revuo (3/5): 165–177. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008.

- ^"Ludwig Lazar Zamenhof – Founder of Esperanto"Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Planned Languages.

- ^"Mapa Polski, mapa Wrocławia, turystyka, wypoczynek - SzukamyPolski.pl". www.szukamypolski.pl. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^Hoffmann, Frank W.; Bailey, William G. (1992). Mind & Society Fads. Haworth Press. ISBN 1-56024-178-0., p. 116Archived 17 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine: "Between world wars, Esperanto fared worse and, sadly, became embroiled in political power moves. Adolf Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf that the spread of Esperanto throughout Europe was a Jewish plot to break down national differences so that Jews could assume positions of authority.... After the Nazis' successful Blitzkrieg of Poland, the Warsaw Gestapo received orders to 'take care' of the Zamenhof family.... Zamenhof's son was shot... his two daughters were put in Treblinka death camp."

- ^"3 россиянина, награждённые орденом Почётного легиона за необычные заслуги (3 Russians Awarded Légion d'honneur for Unusual Merits)". Russian Daily "Sobesednik". 16 August 2013. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^"Nomination archive". NobelPrize.org. 1 April 2020. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^"Espéranto, la langue qui se voulait "universala"". France Inter. 14 April 2017. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^"Olaizola, Borja. "Chatear en Esperanto, vigésimo idioma del mundo más usado en la red." El Correo. 30/03/2011". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^Hommages au Dr Zamenhof, à l'espéranto et à ses pionniers.

- ^"Zamenhofia rosei: Francis' lichen. Range, habitat, biology". Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^Clauzade, G.; Roux, C.; Houmeau, J.-M. (1985). Likenoj de Okcidenta Europa. Ilustrita determinlibro. Bulletin de la Société Botanique du Centre-Ouest (in Esperanto). Vol. 7. Saint-Sulpice-de-Royan. p. 823.

- ^"Ludwik Zamenhof. They left a mark in the history of Odessa". 15 December 2019. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^Ramirez Franzén, Francisco (1 April 2018). "Nytt restaurangkomplex på Esperantoplatsen". Göteborgs-Posten. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^"Francis' lichen - Zamenhofia rosei: More Information - ARKive". Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2007..

- ^Jewish Telegraphic Agency: UNESCO to Honor Memory of Zamenhof, Jewish Creator of EsperantoArchived 4 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 16 December 1959

- ^UnescoArchived 14 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine; UEA: Zamenhof omaĝotaArchived 15 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Google Doodles Archive: 150th Birthday of LL ZamenhofArchived 25 April 2024 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^Jewish Heritage Trail in BiałystokArchived 29 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine accessed 25 July 2009.

- ^Osser, Bernard (13 April 2017). "Esperanto alive and well, 100 years after Jewish inventor's death". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^Salisbury, Josh (6 December 2017). "'Saluton!': the surprise return of Esperanto". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^Kilgannon, Corey (21 December 2017). "Feliĉa Ferioj! Toasting the Holidays in Esperanto". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^Privat, Edmond (1920). "Idealista profeto". Vivo de Zamenhof (in Esperanto). Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^Privat, Edmond (1920). "Verkisto". Vivo de Zamenhof (in Esperanto). Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^Privat, Edmond (1920). "Studentaj jaroj". Vivo de Zamenhof (in Esperanto). Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

Sources

- Boulton, Marjorie (1960). Zamenhof: Creator of Esperanto. Routledge and Paul.

- Forster, Peter G.[in Esperanto] (2013). The Esperanto Movement. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-082456-8.

- Privat, Edmond (1920). The life of Zamenhof. Translated by Eliott, Ralph (1980 ed.). Esperanto Press. ISBN 978-0-919186-08-8 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Korĵenkov, Aleksander[in Esperanto]; Tonkin, Humphrey (2010). Zamenhof: the life, works and ideas of the author of Esperanto(PDF). Translated by Richmond, Ian M. Mondial. ISBN 978-1-59569-167-5. Archived(PDF) from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- Schor, Esther (2016). Bridge of Words. Metropolitan. ISBN 978-0-8050-9079-6.

External links

- Works by L. L. Zamenhof at Project Gutenberg

- Works by L. L. Zamenhof at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by or about L. L. Zamenhof at the Internet Archive

- 1859 births

- 1917 deaths

- 19th-century translators from the Russian Empire

- Bible translators

- Commanders of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Constructed language creators

- Jewish Esperantists

- L. L. Zamenhof

- Linguists of Yiddish

- Inventors from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century Jews from the Russian Empire

- Linguists from Poland

- People from Belostoksky Uyezd

- People from Białystok

- Polish Esperantists

- 19th-century Polish inventors

- Polish Ashkenazi Jews

- Polish ophthalmologists

- Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- Translators to Esperanto

- Translators of William Shakespeare

- Writers of Esperanto literature

- University of Warsaw alumni

- Polish Zionists

- 19th-century Polish Jews

- Polish recipients of the Legion of Honour